Collections

Blue Christmas

Blue Christmas is an imaginative tribute to Christmas archetypes and oneiric figures of 20th century western culture, combining heraldic natural figures with chimeric creatures, as it explores a magical world replete with poetry and the surreal.

Love, grace, and dreams: these are the essence of the tale narrated in this landscape.

The toy soldier who encounters the ballerina, Santa Claus, the angel and the reindeer are all Christmas archetypes in a naturalistic world, narrated by children and cute little squirrels, with a brushstroke reminiscent of the paintings and blues of Chagall.

Christmas Baubles, Figurines and Mugs for dreamers across the ages.

Blue Christmas è un elogio immaginifico agli archetipi del Natale e alle figure oniriche del secolo scorso nella cultura occidentale, mescolando figure araldiche naturali a figure chimeriche, un tuffo in un mondo magico, carico di poesia e di surrealtà.

Amore, grazia, sogno, questo è il sentimento narrato a tratti in questo paesaggio.

Il soldatino che incontra la ballerina, il Babbo Natale, l’angelo, la renna, sono gli archetipi natalizi in un mondo naturalista, narrato dai bimbi e da piccoli scoiattoli, con un tratto che ricorda le pitture di Chagall.

Palle lucenti di Natale, Figurine e Mug per i sognatori di tutti i tempi.

Collections

Objets Bijoux

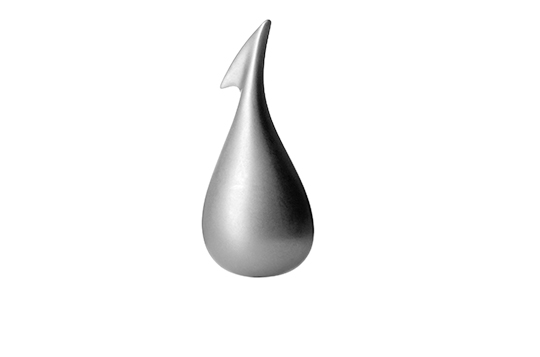

How can we translate those small actions of everyday domestic life into objects of evocative and noble design, much like a piece of jewellery? Small functional objects, designed as jewellery, to be worn or carried. Intriguing items precisely because of their dual nature: instrumental and decorative at the same time. This concept led to the workshop in 2004 and the first “Objet Bijoux” collection.

As part of this new project I wanted to work on what one might call one of Alessi’s original matrices: the manufacture of metals. In the 1990s we had delved into a vast range of highly diverse design areas, experimenting with equally unusual materials for this company. Our “Objet Bijoux” research returned to the innermost core of Alessi’s production identity, namely its ability, from the word go, to produce state-of-the-art metalworking.

Steven Blaess, Francesca Amfitheatrof and Jim Hannon-Tan were the first designers with whom I worked on this project. With Steven Blaess, our starting point was that widespread Australian habit of drinking a soft drink or beer with friends in a casual setting, wherever you happen to be, whether at the beach, on the street, etc. The idea of creating an easily portable bottle opener arose from a small daily gesture – the uncorking a bottle in an informal setting; it was designed as an elegant steel buckle that could be used as an accessory to adorn a belt, to fix a silk scarf or as a pocket key-ring. With Francesca Amfitheatrof we turned out attention to a particular everyday problem: the need to have a coin or token for the supermarket trolley ready to hand. We solved this with the “BON BON” key-ring, where the pendant has a small coin compartment concealed within its soft evocative shape. The project developed with Jim Hannon-Tan, on the other hand, was the outcome of a workshop on “Design Ethics”, inspired by the natural world: starting from the maple seed pod, we created a nutcracker whose design is reminiscent of a small heart.

Over the years, other workshops organised by my studio with other designers have enriched the “Objet Bijoux” collection with a variety of objects, though all sharing some common elements and concepts. First of all, our iconic memory: leaves, hearts, ruffles, droplets, sweets… all the “Objet Bijoux” shapes refer to an archetypal, instantly recognisable icon that resonates in our shared memory. The second aspect is intertwined with the first: since these objects have an evocative shape, their function is often not immediately recognisable; it is hard to grasp at first glance that these organic, natural shapes – linked to our deepest memories – are actually bottle openers, spaghetti-measures, nutcrackers, orange peelers… Another element common to all the items resulting from this research is the tactile dimension: they all have organic, smooth, solid forms that are comfortable to hold and fiddle with. Moreover, they are shiny and reflect light, making them precious and attractive.

Small, elegant and just a little bit mysterious, the “Objet Bijoux” project provides one of the most successful examples of the infinite possibilities of design and shape. Innovative objects that solve practical problems whilst using evocative forms in a totally new and unexpected manner.

Come tradurre le piccole azioni della vita domestica in oggetti dal disegno evocativo e prezioso come quello di un gioiello? Piccoli oggetti funzionali disegnati come monili da indossare o portare con sé, intriganti proprio per questa duplice natura: strumentale e ornamentale al tempo stesso. Da questa suggestione nacque nel 2004 il workshop che portò alla prima collezione degli “Objet Bijoux”.

Con questa nuova ricerca desideravo tornare a lavorare con Alessi su quella che potremmo definire una delle sue matrici originarie: la manifattura dei metalli. Negli anni ’90 avevamo spaziato in ambiti progettuali molto diversi, sperimentando materiali altrettanto inediti per l’azienda. La ricerca sugli “Objet Bijoux” tornava al nucleo profondo dell’identità produttiva di Alessi, al suo essere stata fin dalla fondazione espressione dello stato dell’arte nella lavorazione dei metalli.

Steven Blaess, Francesca Amfitheatrof e Jim Hannon-Tan sono stati i primi designer con i quali ho lavorato a questa ricerca. Con Steven Blaess siamo partiti da un’abitudine australiana molto diffusa, quella di bere una bibita o una birra con amici in modo informale, ovunque ci si trovi, in spiaggia, per strada… Da un piccolo gesto quotidiano – lo stappare una bottiglia in situazioni informali – l’idea di un apribottiglie da portare sempre con sé, disegnato come un’elegante fibbia in acciaio da usare, al tempo stesso, come accessorio per ornare la cintura o fermare un foulard intorno al collo, oppure come portachiavi da tenere in tasca. Con Francesca Amfitheatrof abbiamo invece lavorato su un piccolo problema della vita di tutti i giorni: l’esigenza di tenere sempre a disposizione una moneta o un gettone per il carrello del supermercato. Esigenza che abbiamo risolto con “BON BON”, un portachiavi il cui ciondolo dalla morbida forma evocativa nasconde all’interno un piccolo vano per la moneta. Il progetto con Jim Hannon-Tan è nato all’interno di un workshop dedicato alla “Etica del design”, da un’ispirazione proveniente dal mondo naturale: partendo dalla forma del baccello che racchiude i semi dell’acero, abbiamo creato un aprinoci il cui disegno ricorda al tempo stesso quello di un piccolo cuore.

Negli anni, nuovi workshop organizzati nel mio studio con altri progettisti hanno arricchito la collezione di oggetti molto diversi, sebbene legati da una serie di elementi e suggestioni comuni. Innanzi tutto, il lavoro sulla memoria iconica. Foglie, cuori, gale, gocce, dolci… le forme degli “Objet Bijoux” rimandano a icone archetipe, immediatamente riconoscibili e risonanti nella memoria delle persone. Legato a questo aspetto ve ne è un secondo: proprio perché questi oggetti hanno forme evocative, la loro funzione spesso non è subito riconoscibile. Difficile cogliere a un primo sguardo che queste forme organiche, naturali e connesse a memorie sedimentate sono apribottiglie, dosaspaghetti, aprinoci, sbuccia arance… Un altro elemento comune a tutti i pezzi nati da questa ricerca riguarda la dimensione tattile: gli oggetti hanno forme organiche, lisce, piene, piacevoli da tenere in mano e giocherellare tra le dita. E ancora, forme lucide, riflettenti e per questo preziose e attraenti.

Piccoli, eleganti e un po’ misteriosi, gli “Objet Bijoux” rappresentano uno dei casi più riusciti delle infinite possibilità che il design apre sul piano formale. Oggetti innovativi perché capaci di risolvere un problema funzionale usando forme evocative in modo del tutto inedito e inaspettato.

Collections

Souvenir d’Italie 2015

"Objects such as containers of cultures, emotions, memories ... not mere products"

In French, souvenir means “memory,” and yet souvenir-objects are often shoddy products, trivial reproductions linked to a kitsch imagery, in its most reductive sense. Representations that are very distant from what a memory should be: something rich, personal, multi-faceted ... a container of emotions, images, sensations related to experiences, in a place.

In re-examining the memory-object I immediately felt it was a stimulating project. It gave me the chance to work on the level of relationships between objects and people, which had always been the focus of my research. Objects such as containers of cultures, emotions, memories ... not mere products, but entities in a “lively” sense and therefore able to enter into a relationship with their owners.

The occasion for this rethinking arrived in 2014 with the Universal Exposition, was planned for the following year in Milan. The Expo gave us the opportunity to think about souvenir-objects to offer those who visited Italy to attend the event.

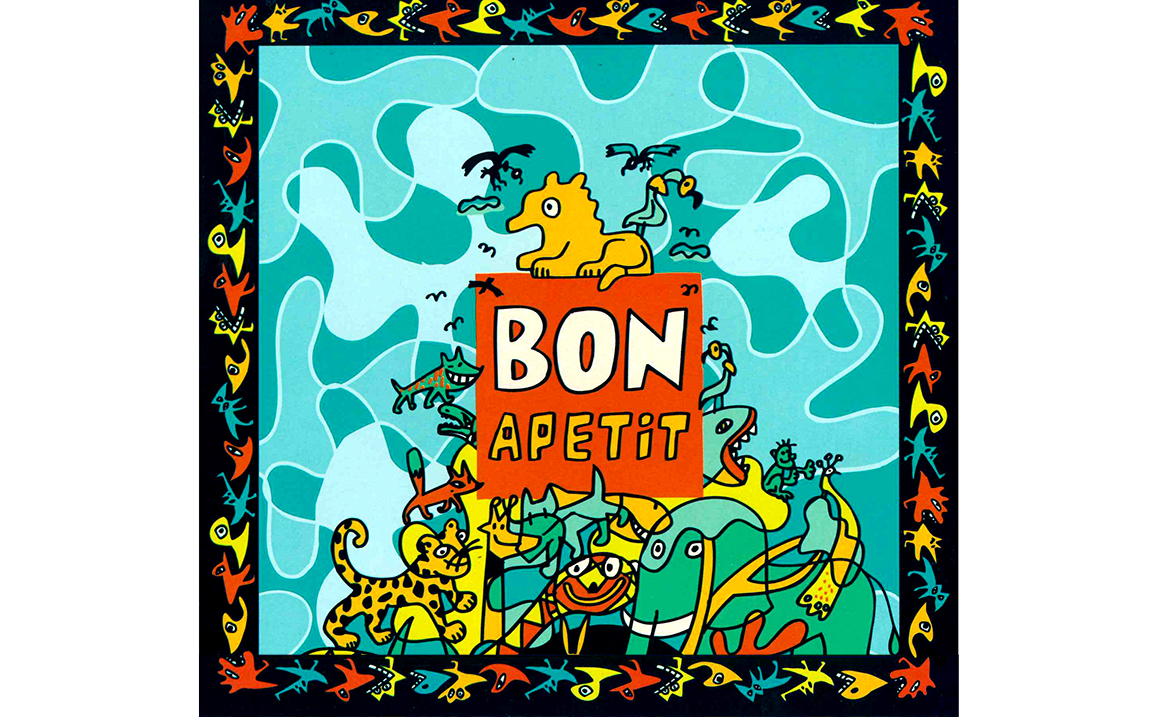

“Souvenir d’Italie”. Together with Massimo Giacon and Antonio Aricò we began to imagine this new collection. Quickly the idea was developed to do a series of character-objects that concentrated on the symbolic traits and elements of Italian cities and regions. Characters that would be sort of caricatures, with an equally evocative name, as “Calabrisella” and “Rosalie the most beautiful ever” by Antonio Aricò or “Lella Mortadella” by Massimo Giacon.

The two designers came up with numerous characters, each able to embody striking elements of the Italian cities and regions we wanted to represent. In early 2015, the approaching inauguration of the Expo required us to radically speed up development time and, consequently, make a drastic selection of projects that would be go into production. In the following May, we presented a small collection consisting of colored porcelain figurines that inaugurated a new way of interpreting souvenir-objects, without betraying their profound meaning nor their important emotional function.

In francese souvenir significa “ricordo”, eppure gli oggetti-souvenir sono spesso prodotti dozzinali, riproduzioni banali legate a un immaginario kitsch, nella sua espressione più riduttiva. Rappresentazioni decisamente lontane da quello che un ricordo dovrebbe essere: qualcosa di ricco, personale, sfaccettato… un contenitore di emozioni, immagini, sensazioni legate a un’esperienza, a un luogo.

Ripensare l’oggetto-ricordo mi è sembrato subito un progetto stimolante. Mi permetteva di lavorare su quelle dimensioni del rapporto tra oggetti e persone che erano sempre state al centro della mia ricerca. Oggetti come contenitori di culture, emozioni, memorie… non meri prodotti, ma entità in un certo senso “animate” e pertanto capaci di entrare in relazione con chi le possiede.

L’occasione per questo ripensamento arrivò nel 2014, offerta dall’Esposizione Universale prevista per l’anno seguente a Milano. L’Expo ci dava l’opportunità di pensare a degli oggetti-souvenir da proporre a quanti sarebbero giunti in Italia per partecipare all’evento.

“Souvenir d’Italie”. Con Massimo Giacon e Antonio Aricò iniziammo a immaginare questa nuova collezione. Nacque subito l’idea di una serie di oggetti-personaggio che concentrassero tratti ed elementi simbolici delle città o delle regioni italiane. Personaggi un po’ caricaturali, con un nome altrettanto evocativo, come “Calabrisella” e “Rosalia la più bella che ci sia” di Antonio Aricò o “Lella Mortadella” di Massimo Giacon.

I due autori disegnarono moltissimi personaggi, riuscendo a racchiudere in ciascuno gli elementi suggestivi delle regioni e delle città italiane che desideravamo rappresentare. Nei primi mesi del 2015, l’avvicinarsi dell’inaugurazione dell’Expo impose una netta accelerazione dei tempi di sviluppo e, conseguentemente, una drastica selezione dei progetti che avrebbero visto la luce. Nel maggio successivo presentammo una piccola collezione composta da colorate figure di porcellana che inaugurarono un nuovo modo di interpretare l’oggetto-souvenir, senza tradirne il significato profondo né l’importante funzione affettiva.

Collections

Transmission 1998

“I have great respect for anyone who dares to venture into unknown territory in order to introduce changes to their own field.” Naoko Takizawa

I feel affinity with the way in which a fashion designer works on a new collection: the design of a suit, a shoe or an accessory is as close as you can get to how I view product design. We both work with different languages, with lifestyles and with items that have a communicative force and so are not just mere objects, but products that interpret the way we live. Communicate who you are, how you feel: you can do this through clothes, just as you can through objects; I see it in the same way. Then there is the coming-together of several areas of expertise, the search for the right material, the enrichment gained by drawing on different ideas. Even the fact of the changing seasons and new trends, not to mention that of mixing languages, high and low culture, the street and art with a capital A, cartoons and the movies.

Fashion designers create worlds that make people go crazy, that generate aggregation, emotion, communication and particularly strong immersive experiences. They build up new experiences.

Another shared aspect is the performance dimension of couture: a dress presented during a fashion show is like a theatrical performance. I have actually used a fashion show for FFF; several times I have acted more in the way of a fashion designer than an industrial design project manager.

The idea of transmission arose from my great love for fashion: to get a group of fashion designers, in other words ‘creators of style’, involved in a project. These are creators of lifestyle, communication, taste and new aesthetic frontiers. It was not simply a matter of linking an object with a popular fashion label, but the actual development of a design and production method capable of creating a transversal flow of communication, one that could link different worlds. Hence the name ‘Transmission’, i.e. the transmission, communication and exchange of skills and expertise, know-how, sensitivity, competence and understanding. Fashion designers were asked to breathe life into the idea that is at the root of their creativity, namely the ‘concept’, but instead of developing a suit or an accessory, they were expected to develop an object. This new object had to fit one of the product categories already developed by Alessi: personal accessories, bedtime accessories (eye masks, teddy bears, bedside table lamps, alarm clocks, etc.), personal care (toothbrushes, makeup bags, bath towels, soap holders, vibrators, etc.) and so on. My aim was to allow fashion designers to investigate these new product categories and so create transmission…

Paco Rabanne, Walter Van Beirendonck, Naoki Takizawa, Manolo Blahnik, Yoshi Yamamoto, Hussein Chalayan, Lawrence Steele and Marco Berardi: Andrea Tenerani has helped boost their communication strategies.

Even if the resulting objects never actually went into production, the dialogue created between these two worlds helped further the Centro Studio Alessi’s reputation for being an enterprising design workshop. In 2000 the results of this experience were published in a magazine – DUE – whose goal was to bring together various aspects of fashion, design and lifestyle. This was presented to the public on the 13th of April 2000 in Corso Matteotti, Milan.

“Rispetto tutti coloro che si inoltrano in territori inesplorati al fine di operare un cambiamento nel proprio campo” Naoko Takizawa

Sento affinità con il modo in cui operano gli stilisti, la progettazione di una collezione , di un abito, una scarpa, un accessorio è quanto di più affine alla progettazione come la intendo. Entrambi lavoriamo sui linguaggi differenti, su lifestyle, sui modi del vivere sugli oggetti che comunicano e non sono solo oggetti, su un prodotto che è interpretazione del vivere. Comunicare come sei, come stai: lo fai attraverso i vestiti come attraverso gli oggetti., io lo vedo nello stesso modo. E poi l’unione di più conoscenze, la ricerca dei materiali, il nutrirsi di immaginari differenti . Anche il fatto della stagionalità, del cambiare. E poi il fatto del mescolare i linguaggi, del mescolare cultura alta e bassa, la strada e l’arte, il fumetto e e il cinema.

Gli stilisti creavano dei mondi che facevano impazzire le persone, aggregazione, emozione, comunicazione, esperienze immersive fortissime. Addensatori di esperienze.

E poi anche la dimensione performante della moda, il vestito presentato nella sfilata, come performance, io avevo usatpo una sfilata per FFF, più volte mi ero mossa in modo più affine a quello di uno stilista di moda che di project manager di industrial design

Da questa grande amore per la moda nacque l’idea di trasmission: coinvolgere un gruppo di stilisti, ovvero di creatori di stili: di vita, di comunicazione, di gusto, di frontiere estetiche. Non era il banale abbinamento di un oggetto a una griffe più o meno nota, ma mettere a punto un modo di progettare e produrre capace di creare una corrente di comunicazione trasversale anche tra mondi diversi. Di qui il nome Transmission, ossia trasmissione di competenze, trasferimento, comunicazione e scambio di competenze, di saperi, sensibilità, competenze, conoscenze. Agli stilisti viene chiesto di attivare l’dea che sta alla radice del loro lavoro creativo, il “concept”, anziché su di un abito o un accessorio, su un oggetto: al fianco delle tipologie già indagate dalla storia alessi, accessori per la persona, per il dormire (mascherine per gli occhi, orsacchiotto, abatjour, sveglia….), prendersi cura (spazzolino per denti, trousse, telo spugfna, portasapone, vibratore…). Con gli stilisti pensavo che questi nuovi ambiti tipologici potessero essere indagati creando, appunto, una transmission…

Paco Rabanne, Walter Van Beirendonck, Naoki Takizawa, Manolo Blahnik, Yoshi Yamamoto e Hussein Chalayan, Lawrence Steele, Marco Berardi. Andrea Tenerani si occupava della comunicazione di alcuni di loro

Anche se non si avviò una vera produzione industriale di tali proposte, il dialogo instaurato tra questi due mondi contribuì ad alimentare l’aspetto intraprendente del Centro Studio Alessi, che riuscì poi, nel 2000, a tradurre questa esperienza in una pubblicazione: la rivista DUE, un magazine che ambiva a coniugare diversi aspetti della moda, della progettazione e degli stili di vita e che fu presentato il 13 aprile dello stesso anno in Corso Matteotti a Milano.

Collections

Kids Projects 2003

What objects do children want? The most logical thing to do is to ask them and that’s what we did in 1996, organizing a workshop at an elementary school in Milan with the help of a team of animators.

For several years we had won over a growing number of people with objects that, although meant for adults, could also talk to children. Indeed, I believe that the success of these products — like “Gino Zucchino” by Guido Venturini, “Lilliput” by Stefano Giovannoni or “Diabolix” by Biagio Cisotti — was precisely due to the fact that they could speak to a generation of “new adults” ( or ““big kids”) who had grown up with the imagery of cartoons.

The result of the workshop conducted in the school in Milan was truly amazing: a huge, 10-meter-long roll of paper full of inventions, animated objects capable of impossible functions and with poetic qualities. With those drawings we had disembarked in a fantastic and surreal world, but one that was enormously stimulating from a creative point of view. That first experiment begat reflections and thoughts, giving rise to a further series of workshops organized in Argentina, Costa Rica, Japan and Korea. After these, we decided to design a family of objects intended solely for children.

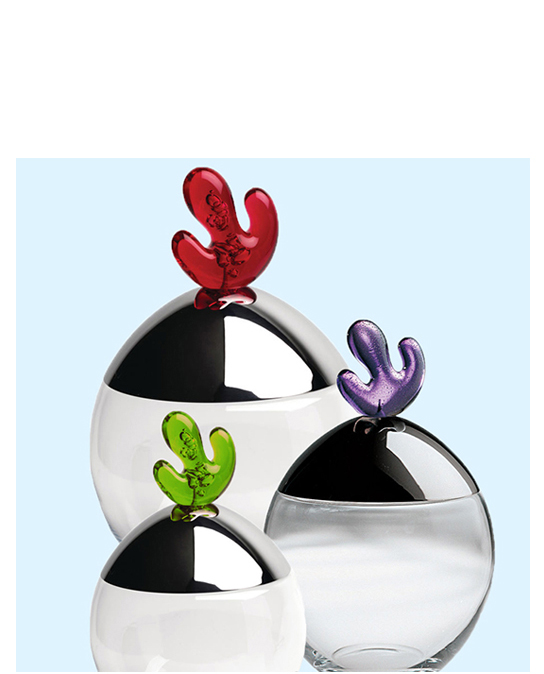

The meeting with Reggio Children was instrumental in the development of our work. They helped us to define the way forward by identifying the functions that objects take on in the organization and practice of a child’s day. We decided to start by designing tableware, establishing the qualities and characteristics they should have. First of all, to interact with children’s imaginations and act as a go-between in a sensorial relationship with other objects. Beyond that — and most importantly — to communicate with light. In this way we came to think about objects that had, as an aesthetic feature, transparency and kaleidoscopic qualities. Utilitarian, daily objects with whom the children could improvise a relationship with the surrounding world, having been provided with the same quality of glass and with the poetry of light, broken down into a thousand colors.

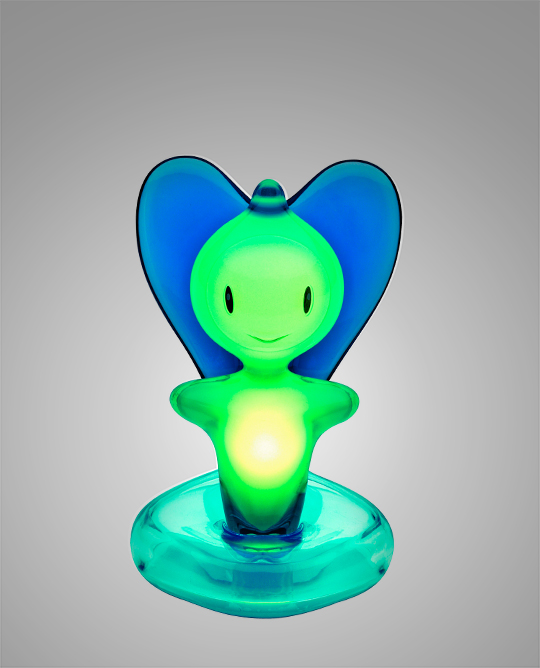

I worked on this project together with Lorenza Bozzoli and Massimo Giacon. With Lorenza we concentrated on the splendor of the kaleidoscope, on the possibility of translating into plastic plates, bowls and cups the magic of decomposing light. With Massimo, we instead dedicated ourselves to the design of cutlery, recuperating research done on the animistic dimension of objects that had been developed in the early 90s with the Alessi Study Centre.

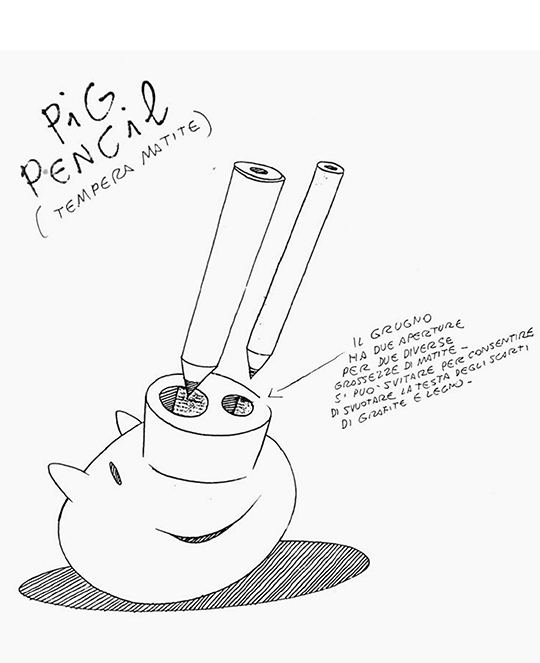

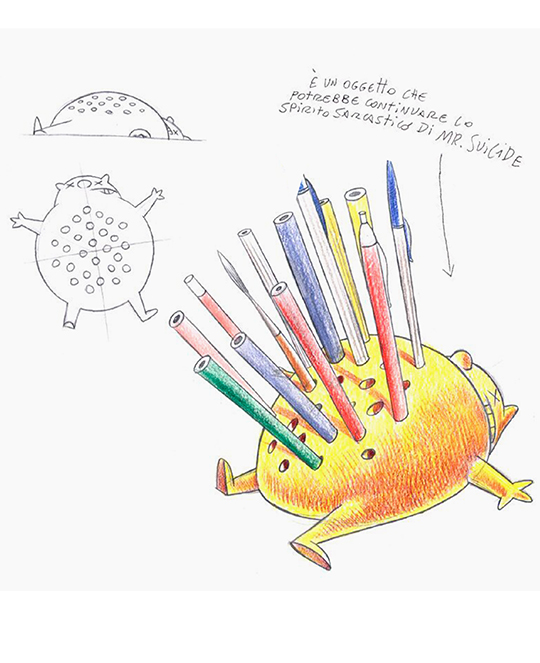

Having initiated the research to realize this first collection of objects, I began to think of other types: night lights, desk objects… It was a proposal from Rasch, a company specialized in the production of wallpaper, which allowed me to further broaden the scope of typological research. Again, it involved Massimo Giacon, with Marcello Jori, Miriam Mirri and Stefano Pirovano in the “Wall+Paper” collection presented in 2001. With Miriam Mirri, we later designed “Beba Light”, a small luminous being that keeps children company while they sleep. Between 2003 and 2004, again with Massimo Giacon, we realized the “Pig Pencil” sharpener and the pencil “Sebastiano”; in the same period, with Kim H. J. Mika, we created the clip holder “Dozi” during a workshop organized to KIDP Seoul.

If I look at the family of objects created from the first experiments developed with the children in Milan, I cannot help but see myself in the words of Vea Vecchi, Carla Rinaldi, Claudia Giudici, the educators of Reggio Children who shared with us the beginning of this adventure:

“Children as well as grown-ups have the right to enjoy beautiful things, in the same way as they do art. A right that must be exercised in day-to-day living. Art [...] is an experience, the perception of beauty on an almost daily basis, which takes place in the world, in life, and gives meaning and value to human existence. The aim of the research was grant this right to small children, also through the use of everyday utensils. [...] Everyday, parent and child can create a new story inspired by the interplay between the cutlery, whose shape is so evocative, and the shape and colours of the food - not to mention the aromas -which are multiplied by the kaleidoscopic effects created by the dishes and the glass. The very fact that we have adopted a light-hearted approach that reflects an awareness and sensivity to the taste and presentation of food, to pleasure as an ingredient of everyday life, to the social and convivial aspects of mealtimes and to dining as an expression of culture, indicates a ‘multifaceted’ approach to life and to reaching out other people”

Bruno Munari

Quali oggetti vogliono i bambini? La cosa più logica da fare è chiederlo a loro: è quello che abbiamo fatto nel 1996, organizzando un workshop in una scuola elementare di Milano con l’aiuto di un gruppo di animatori.

Da alcuni anni avevamo conquistato un numero sempre crescente di persone con oggetti che, sebbene pensati per adulti, sapevano parlare anche ai bambini. Anzi, credo che il successo di quei prodotti – come “Gino Zucchino” di Guido Venturini, “Lilliput” di Stefano Giovannoni o “Diabolix” di Biagio Cisotti – fosse proprio dovuto al fatto che sapessero parlare a quella generazione di “nuovi adulti” (o “bambini grandi”) cresciuti nell’immaginario dei cartoni animati.

Il risultato del workshop realizzato nella scuola di Milano fu davvero sorprendente: un enorme rotolo di carta con 10 metri d’invenzioni, oggetti animati capaci di funzioni impossibili e dotati di qualità poetiche. Sbarcavamo con quei disegni in un mondo fantastico e surreale, ma enormemente stimolante dal punto di vista creativo. Quel primo esperimento generò riflessioni e pensieri, dando vita a una serie ulteriore di workshop organizzati in Argentina, Costa Rica, Giappone e Corea, dopo i quali pensammo di affrontare il progetto di una famiglia di oggetti destinati esclusivamente ai bambini.

L’incontro con Reggio Children fu determinante nello sviluppo del nostro lavoro. Ci aiutarono a definire il modo in cui procedere, individuando le funzioni che gli oggetti assumono nell’organizzazione e nella pratica della giornata di un bambino. Decidemmo di iniziare dalla progettazione di oggetti per la tavola, stabilendo le qualità e le caratteristiche che avrebbero dovuto avere. Innanzitutto interagire con la fantasia dei bambini ed essere tramite di una relazione sensoriale con gli altri oggetti, inoltre – e soprattutto – dialogare con la luce. Pensammo così a oggetti che avessero come caratteristica estetica la trasparenza e la qualità del caleidoscopio. Oggetti d’uso con i quali i bambini avrebbero potuto improvvisare una relazione con il mondo circostante, provvisti della stessa qualità del vetro e della poesia della luce scomposta in mille colori.

Lavorai al progetto insieme a Lorenza Bozzoli e Massimo Giacon. Con Lorenza ci concentrammo sulla suggestione del caleidoscopio, sulla possibilità di tradurre la magia della scomposizione della luce in piatti, ciotole e bicchieri realizzati in plastica. Con Massimo ci dedicammo invece al disegno delle posate, recuperando la ricerca sulla dimensione animistica degli oggetti sviluppata nei primi anni’90 con il Centro Studio Alessi.

Avviata la ricerca per realizzare questa prima collezione di oggetti, iniziai a pensare ad altre tipologie: luci per la notte, oggetti per la scrivania… Fu una proposta proveniente dalla Rasch, un’azienda specializzata nella produzione di carte da parati, che mi permise di allargare ulteriormente l’ambito tipologico della ricerca. Coinvolsi nuovamente Massimo Giacon, insieme a Marcello Jori, Miriam Mirri e Stefano Pirovano nella collezione “Wall+Paper”, presentata nel 2001. Con Miriam Mirri, progettammo in seguito “Beba Light”, un piccolo essere luminoso che accompagnava il sonno dei bambini. Tra il 2003 e il 2004, di nuovo con Massimo Giacon, realizzammo il temperamatite “Pig Pencil” e il portamatite “Sebastiano”; nello stesso periodo con Kim H. J. Mika creammo il portafermagli “Dozi” durante un workshop organizzato al KIDP di Seul.

Se guardo alla famiglia di oggetti nati a partire dalla prima sperimentazione sviluppata con i bambini di Milano, non posso non ritrovarmi nelle parole di Vea Vecchi, Carla Rinaldi, Claudia Giudici, le educatrivci di Reggio Children che hanno condiviso con noi l’inizio di questa avventura:

“Il bello, così come l’arte, è un diritto del bambino come dell’uomo. Un diritto che va esercitato nel quotidiano: l’arte […] è esperienza, un’attività percettiva del bello pressoché quotidiana che si fa nel mondo, nella vita e che dà senso e valore all’agire umano. Riconoscere questo diritto al bambino piccolo, anche a partire dagli utensili del quotidiano, è stato l’obiettivo della ricerca […] Sarà così possibile costruire ogni giorno, da parte del bambino e del genitore, una storia nuova che nasce dall’incontro tra la forma delle posate, così evocativa, e la forma, i colori e gli odori del cibo, che si moltiplicano con le sfaccettature dei piatti e del bicchiere. Perché proprio un approccio giocoso, consapevole e sensibile al gusto e all’estetica del cibo, al piacere come qualità del quotidiano, alla socialità e convivialità del pasto, all’alimentazione come momento di espressione culturale, è un atteggiamento complesso di fronte alla vita e di apertura verso gli altri”.

Bruno Munari

Metaproject stories

Collections

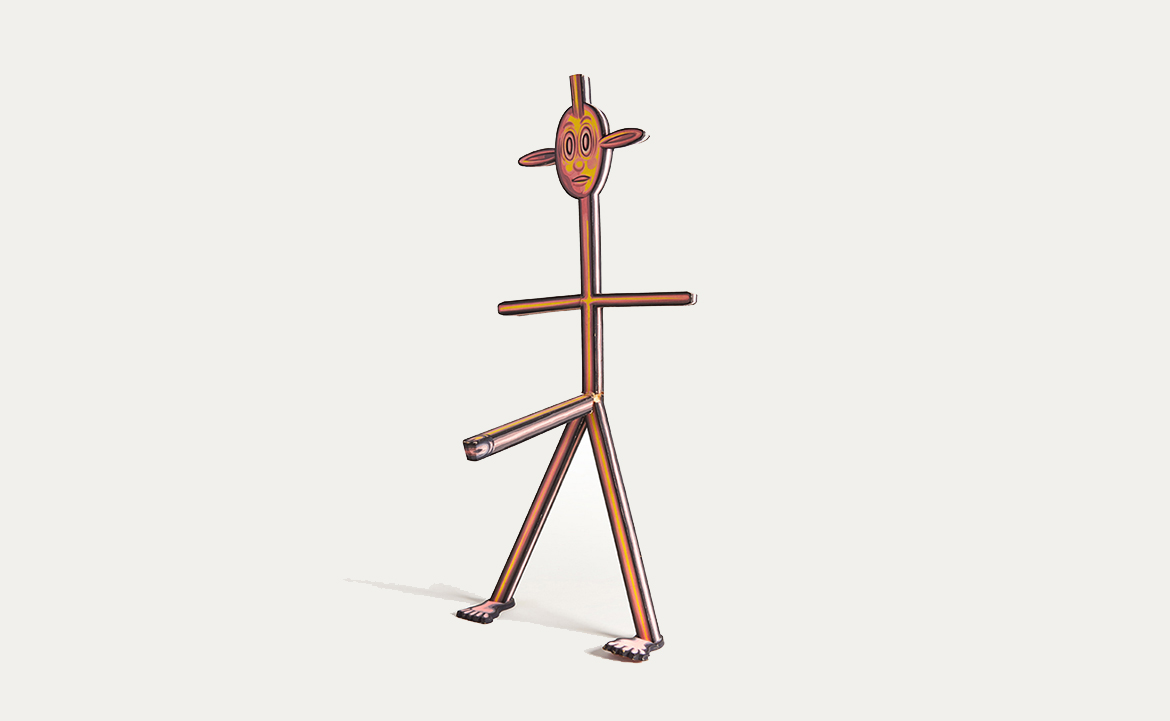

Figure 2007

"The Figurines were developed addressing the notion of objects understood as entities possessing a soul"

It’s difficult to define having encountered Massimo Giacon and Marcello Jori, two very different artists in terms of language, work, personality… I certainly couldn’t have done it on a strictly professional basis and what I’ve built up with them over the years is a very full and rewarding association, especially on a personal and human level. If I think about these two designers now, I think of two friends with whom I’ve shared key projects and formative experiences, to the point that at a certain juncture in our collaboration we founded “JPG”.

Our work together began at separate moments in time and on different research projects. The new millennium, however, found us working on the same subject: a collection of small figurines to be made in porcelain.

The idea of a “Figurines” collection came from a line of research important for me, which ever since the early years of collaborating with Alessi had driven my work, that of the fetish object. The “Figurines” were developed as part of a new project addressing the notion of objects understood as entities possessing a soul.

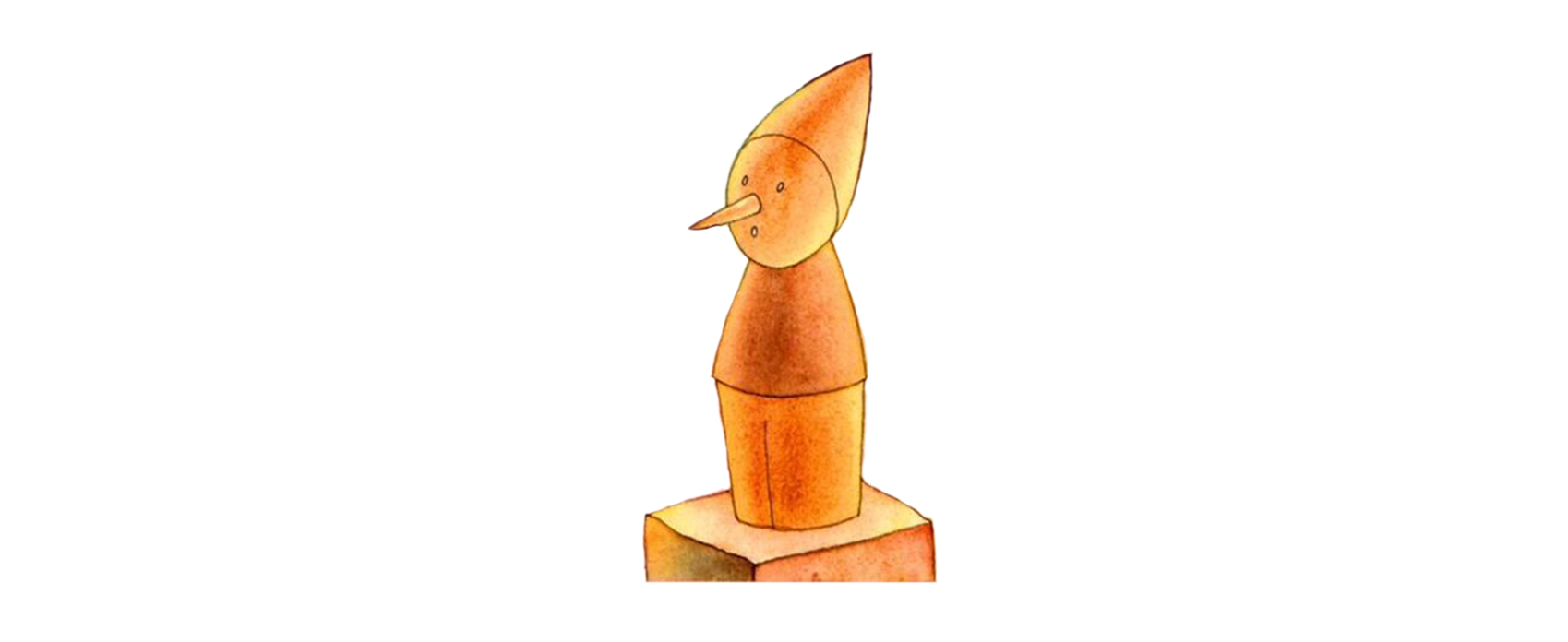

Accustomed to the freedom offered by comic books, where the artist works alone in total autonomy, creating the characters and deciding their fates, I suggested to Massimo Giacon that he approach design by treating objects as if they were elements of a story. Marcello Jori approached the field of design from an entirely different perspective: his roots in the art world. For Jori, design offered the opportunity to achieve that which painting and writing did not allow: “useful art”, as he came to define it. Objects that could serve to change people’s mood, lift their spirits, make them smile. “Pinocchino”, “Topolone”, “Marzio”, “Mago Sterlino,” “Rudy and Sventola””... these are some of the “Figurines” he created: benevolent, poetic presences that are a little magic, ready to gently enter our homes.

In 2006 the first “Figurines” designed with Jori were ready, followed a year later by those created with Giacon: a series of characters that spawned micro narratives related to Christmas. Since then, we’ve gotten together many times to discuss ideas, characters, new creatures, each in its own way bearing little tales to accompany us in our daily lives.

Difficile definire l’incontro con Massimo Giacon e Marcello Jori, due artisti diversi per linguaggio, opera, personalità… certamente non potrei farlo in termini esclusivamente professionali, poiché quello che ho costruito con loro negli anni è un sodalizio molto ricco, soprattutto sul piano umano e personale. Se penso ora a questi due autori, penso a due amici con i quali ho condiviso progetti ed esperienze fondamentali, tanto che a un certo punto della nostra collaborazione fondammo la “JPG”.

La collaborazione con loro è iniziata in momenti e in occasione di ricerca differenti, ma con il nuovo millennio ci trovammo a lavorare su uno stesso tema: una collezione di piccole figure da realizzare in porcellana.

L’idea di una collezione di “Figure” nasceva da un filone di ricerca per me importantissimo, che aveva orientato il mio lavoro fin dai primi anni di collaborazione con Alessi, quello dell’oggetto feticcio. Le “Figure” declinavano in un nuovo progetto il tema dell’oggetto inteso come presenza animata.

Abituato alla libertà offerta dal fumetto, dove l’autore lavora da solo creando in totale autonomia i personaggi e i loro destini, suggerii a Massimo Giacon di avvicinarsi alla disegno di oggetti trattandoli come gli elementi di una storia. Marcello Jori si accostò al lavoro di progettazione da un punto di vista completamente diverso, quello del mondo dell’arte dal quale proveniva. Il design per Jori offriva la possibilità di realizzare ciò che la pittura e la scrittura non gli permettevano: “arte utile”, come lui stesso ebbe modo di definirlo. Oggetti che servono alle persone per cambiare il loro umore, sollevare lo spirito, suscitare un sorriso. “Pinocchino”, “Topolone”, “Marzio”, “Mago Sterlino”, “Rudy e Sventola”… queste alcune delle “Figure” create con lui: presenze benevoli, poetiche, un po’ magiche, pronte ad entrare con leggerezza nelle nostre abitazioni.

Nel 2006 erano pronte le prime “Figure” disegnate con Jori, l’anno successivo seguirono quelle create con Giacon: una serie di personaggi che diedero vita a delle micro narrazioni legate al Natale. Da allora ci siamo trovati molte volte a discutere idee, personaggi, nuove creature, ciascuna a suo modo portatrice di piccole storie nel nostro quotidiano.

Metaproject stories

Collections

F.F.F. (Family Follows Fiction)1993

"Family Follows Fiction wanted to create objects that were like characters, actors in a 'fiction', storytellers of relation"

“Play is a serious matter.” In February 1991 I began an intense exchange of thoughts and reflections with Alberto Alessi, Franco La Cecla, Marco Migliari and Luca Vercelloni. Gradually a new scenario to be explored took shape, “the object-toy”. Play is the first good practice in understanding the world around us. Children use it to experiment, learn, get in touch, meet deep needs, emotional, intimate, sensorial. In our reflection, Franco Fornari’s theory of affective codes as well as the writings of Donald W. Winnicott on transitional objects and paradoxical thinking, offered ulterior tools to our investigation.

In a room full of objects, a child will choose one to escape boredom and loneliness, but why that one? The challenge was to reproduce in the project the animistic process common to children’s and primitive cultures’ representation of the world. A process that occurs spontaneously, caused by the emotional needs of individuals: to give a soul to inorganic and inanimate objects. Recognizing that they are capable of acting allows us to interpret an otherwise dark and threatening world.

In April, we were ready. Pierangelo Caramia, Stefano Giovannoni, Massimo Morozzi, Giovanni Lauda, Alejandro Ruiz, Denis Santachiara and Guido Venturini, these were the designers involved in this new meta-project, chosen because we felt that they would be able to interpret the communicative dimension of the objects that we wanted to explore. Between subject and object, in addition to the instrumental relationship, there is also the “communicative” one. That relationship is the object to “communicate”, to have an effect on the subject. We wanted to highlight the affective valence of objects when they “act” on people not just mere tools but as entities with emotional qualities through which they become desirable, tender, inseparable. The consumer object is elevated to a poetic and imaginative structure, capable of touching individuals’ emotional chords.

“F.F.F.” the title of the workshop, paraphrased “Form Follows Function”, the famous axiom of Louis Sullivan. With our research we entered into a new dimension of design: “Family Follows Fiction”. It wanted to create objects that were like characters, actors in a “fiction”, storytellers of relational stories. The objects on the table thereby became a family of little creatures, animate beings capable of creating relationships in the domestic world.

This research was accompanied by the exploration of possible new materials with which to produce objects. Until then Alessi had only worked with metals, mainly steel, but other materials — such as plastic — seemed better suited to explore the world of color and the scope of an object’s sensorial pleasures, more akin to the emotional and relational dimensions we wanted to investigate

It was a pleasurable project. We can say that we enjoyed it. The result was a new chapter in the world of Alessi: objects that were maybe more autonomous, able to have an independent relationship with the world, alluding to unknown imagery or, in other cases, to fantastic worlds… some creatures were born.

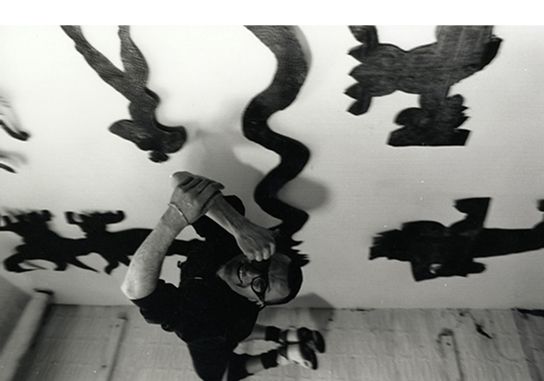

In 1993, the objects created by the workshop were presented with a big event organized in Milan, a celebration that was a project within the project. In a striking industrial building no longer in use we realized a scene composed of lights and graffiti. We involved a demented rock band that played throughout the evening. Objects, reproduced in the form of large paper mache hats, marched into that space worn by models. All around, there was an evocative set design created by a sequence of works by Mattia Di Rosa: panels painted in tempera, each with a small shelf that displayed the actual products.

“Il gioco è una cosa seria”. Nel febbraio del 1991 iniziai un fitto scambio di pensieri e riflessioni con Alberto Alessi, Franco La Cecla, Marco Migliari e Luca Vercelloni: progressivamente si delineò un nuovo scenario da esplorare, “l’oggetto-giocattolo”. Il gioco è la prima buona pratica per comprendere il mondo, il bambino lo usa per sperimentare, conoscere, entrare in relazione, soddisfare bisogni profondi, affettivi, intimi, sensoriali. Nella nostra riflessione, la teoria dei codici affettivi di Franco Fornari e i testi di Donald W. Winnicott sull’oggetto transizionale e sul pensiero paradossale, ci offrirono ulteriori strumenti per la nostra indagine.

In una stanza piena di oggetti un bambino ne sceglie uno per uscire dalla noia e dalla solitudine: perché proprio quello? La sfida era di riprodurre nel progetto il processo animistico comune alla rappresentazione del mondo propria dei bambini e delle culture primitive. Processo che avviene spontaneamente, provocato dalle esigenze emotive degli individui: attribuire un’anima anche agli oggetti inorganici e inanimati, riconoscendoli così capaci di agire, permette di interpretare un mondo altrimenti oscuro e minaccioso.

In aprile eravamo pronti. Pierangelo Caramia, Stefano Giovannoni, Massimo Morozzi, Giovanni Lauda, Alejandro Ruiz, Denis Santachiara e Guido Venturini, questi i designer coinvolti in quel nuovo metaprogetto, scelti perché sentivamo che sarebbero stati in grado di interpretare quella dimensione comunicativa degli oggetti che desideravamo esplorare. Tra soggetto e oggetto, oltre alla relazione strumentale, esiste quella “comunicativa”. In tale relazione è l’oggetto a “comunicare”, ad avere effetto sul soggetto. Desideravamo evidenziare la valenza affettiva degli oggetti, quando “agiscono” sulle persone, non più soltanto meri strumenti ma entità dotate di qualità emozionali attraverso le quali diventano desiderabili, teneri, inseparabili. L’oggetto di consumo si elevava a struttura poetica e immaginifica, in grado di andare a toccare le corde emotive degli individui.

“F.F.F.”, il titolo del workshop, parafrasava “Form Follows Function”, il famoso assioma di Louis Sullivan. Con la nostra ricerca entrammo in una nuova dimensione del progetto: “Family Follows Fiction”. Si desiderava creare oggetti che fossero come personaggi, attori di una “fiction”, narratori di storie relazionali. Gli oggetti sulla tavola divenivano così una famiglia di piccole creature, esseri animati capaci di tessere relazioni nel mondo domestico.

Questa ricerca si accompagnò all’esplorazione di nuovi possibili materiali con i quali produrre gli oggetti. Fino ad allora Alessi aveva lavorato solo con i metalli, principalmente l’acciaio, ma altri materiali – per esempio la plastica – apparivano strumenti migliori per esplorare il mondo del colore e l’ambito del piacere sensoriale dell’oggetto, più affine alle dimensioni affettive e relazionali che volevamo indagare.

È stato un progetto felice, possiamo dire che ci siamo divertiti. Il risultato è stato un nuovo capitolo del mondo Alessi: oggetti forse più autonomi, in grado di avere con il mondo una relazione indipendente, allusiva a immaginari conosciuti o, in altri casi, a mondi fantastici… sono nate delle creature.

Metaproject stories

Object

Collections

Bio Object 1992

"Bio Object a research about the natural, biological memory"

Florence, School of Architecture: it was here, in 1992, that the Biological Object workshop took place with the students from Remo Buti’s course on Design and interior Architecture.

“Domestic object” and “Organic object”, these were the two nuclei around which I wanted to move. The domestic object was the type that I wanted to investigate with the workshop. The natural world, instead, offered the imagery to which we would refer in developing the projects.

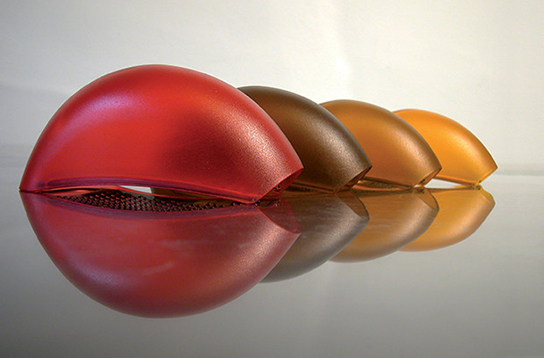

This is how the new research began, an exploration of the various household types formally inspired by suggestions offered by nature: functional objects, whose forms would look to the organic world, the living. A year earlier, with the “Memory Containers” workshop, we investigated the object intended as a storage enclosure, the personal, cultural and geographical. With the new research, I wanted to work with natural memory, biological, particularly focusing on sea life. In the images of marine organisms, I could see extremely ancient forms of the natural world, charged with this memory. The metaproject theme chosen also required materials that were capable of transmitting feelings of delicacy and softness. The biological object had to be able to transmit a seductive sensoriality, also through a particular use of materials, finishes and color.

After the workshop in Florence, I continued the research in Milan, at the headquarters of the Alessi Study Centre and, in 1994, “Parmenides” was the result. A biological object par excellence, the grater with holder designed by Alejandro Ruiz was the first product in the Study Centre to be acquired for MoMA’s permanent collection in New York. It quickly became one of the most popular products of that period. “Parmenides” has a shape that was clearly inspired by a sea-shell, whose proportions were designed by applying the golden ratio.

Over the years, the language related to biological memory led to other workshops, such as “Lightness of Steel” held in 2004. At the time, there were also other collections able to communicate with a public increasingly broadened through the imagery to which the objects were explicit references: organic forms, delicate, instantly recognizable by our sensory memory, because they are part of a profound experience that binds us to the living world to which we all belong.

Firenze, Facoltà di Architettura: fu qui che nel 1992 ebbe luogo il workshop sull’Oggetto biologico, con gli studenti del Corso di Laurea in Progettazione, Arredamento e Architettura degli interni di Remo Buti.

“Oggetto domestico” e “oggetto organico”, questi i due nuclei intorno ai quali desideravo muovermi. L’oggetto domestico era la tipologia che volevo indagare con il workshop, il mondo naturale offriva invece l’immaginario al quale fare riferimento per sviluppare i progetti.

Nacque così quella nuova ricerca, un’esplorazione delle varie tipologie domestiche ispirata formalmente alle suggestioni offerte dalla natura: oggetti funzionali, le cui forme avrebbero rimandato al mondo organico, vivente. Un anno prima, con il workshop “Memory containers”, avevamo indagato l’oggetto inteso come contenitore di memoria, quella personale, culturale e geografica. Con la nuova ricerca desideravo lavorare con la memoria naturale, biologica, in particolare quella marina. Nelle figure degli organismi marini vedevo le forme più antiche e cariche di memoria del mondo naturale. Il tema metaprogettuale scelto richiedeva inoltre materiali capaci di trasmettere sensazioni di delicatezza e morbidezza. L’oggetto biologico doveva poter trasmettere una sensorialità seduttiva, questo anche attraverso un uso particolare dei materiali, delle finiture e del colore.

Dopo il workshop a Firenze, continuai la ricerca a Milano, nella sede del Centro Studi Alessi e, nel 1994 nacque “Parmenide”. Oggetto biologico per eccellenza, la grattugia con raccoglitore disegnata da Alejandro Ruiz fu il primo prodotto nato nel Centro Studi ad essere acquisito dalla collezione permanente del MoMa di New York. Divenuta rapidamente uno dei prodotti più apprezzati di quel periodo, “Parmenide” ha una forma chiaramente ispirata al guscio di una conchiglia marina, le cui proporzioni sono state disegnate applicando la sezione aurea.

Il linguaggio legato alla memoria biologica ha guidato negli anni altri workshop, come “Lightness of Steel” realizzato nel 2004 . Nel tempo sono nate collezioni capaci di dialogare con un pubblico sempre più allargato grazie all’immaginario al quale gli oggetti facevano esplicito riferimento: forme organiche, delicate, immediatamente riconoscibili dalla nostra memoria sensoriale, perché appartenenti a un vissuto profondo che ci lega al mondo vivente di cui siamo parte.

Metaproject stories

Object

Collections

Memory Containers 1991

“Memory Containers. The metaproject that gave voice to women within the industrial design scenes.”

“The meta-project “Memory Containers” marks the start of Alessi reaching out to young designers; to young female designers to be precise. In its early stages, some 200 women designers under 30 from all over the world were invited to participate. The questions we asked ourselves were: what is expected of the object; what can it achieve? How are objects conceived or how are they transformed as they transit between different cultures? What changes occur in their form, in how they are perceived, used? How does an object become a topic of culture? The typological exploration referred to the archetypes of how food is presented and ‘offered’, and how these customs are tied to the memory of a culture or a personal experience. This ‘Creole’ project is an in vitro cloning of what, had it occurred naturally over time, would have evolved much more slowly as a result of encounters between different cultures.” Alberto Alessi

Memories, offering rituals, women: these are the three nuclei of the first meta-project I developed for Alessi. Memories: the cultural ones composed of elements shared by those who live in a certain place and time, and the personal ones, intimate, private. Offering: a ritual found in every culture across the globe, manifesting itself in various forms: offerings to the gods, to ancestors, friendly ones among friends… And finally women: with that first research, the desire for experimentation and openness that had led Alessi to create the Centro Studi, reached out to include the world of women in design as well. “Memory Containers” gave voice to a part of the creative scene that until then had not had many opportunities to express itself in the world of industrial design.

9 objects — “Memory Containers” — resulted from the workshops. These were soon were joined by others, adding 15 more to the initial challenge. Images of the projects, as well as the cultural and personal references that inspired them, were collected in a publication, “Rebus sic ...”, together with the writings of Paolo Fabbri, Lucetta Scaraffia and Franco La Cecla who participated in the creation of the first meta-project.

The book and the “Memory Containers” were presented with a big party in October 1991, organised in the Art Nouveau building of the Hippodrome in Milan. The centrepiece of the event was a performance where a surreal series of bizarre characters wore objects from the collection on stage. It was an exciting time, which was attended by more than a thousand guests: one of the first major events dedicated to design that involved the city itself.

“Il metaprogetto Memory Containers rappresenta il momento di apertura di Alessi ai giovani designer; anzi, per la verità alle giovani designer, dal momento che nella fase iniziale sono state invitate circa 200 progettiste donne under 30 da tutto il mondo. Le domande che ci ponevamo erano: quali sono le competenze dell’oggetto? Come nascono o si trasformano gli oggetti nel passaggio tra diverse culture? Che cosa cambia nella loro forma, nella percezione, nell’uso? Come fa un oggetto a diventare soggetto culturale? L’esplorazione tipologica si riferiva agli archetipi della presentazione e della ‘offerta’ del cibo, legati alla memoria di una cultura o di una esperienza personale. Questo progetto ‘creolo’, è una clonazione in vitro di ciò che, con tempi naturali, avviene molto più lentamente come risultato dell’incontro fra culture diverse.” Alberto Alessi

La memoria, il rituale dell’offrire, la donna: questi i tre nuclei del primo metaprogetto che ho sviluppato per Alessi. La memoria: quella culturale fatta di elementi condivisi da chi vive in un certo luogo e tempo, e quella personale, intima, privata. L’offrire, un rituale presente in tutte le culture del mondo, in forme diverse: l’offerta agli dei, agli antenati, quella conviviale tra amici… E infine la donna: il desiderio di sperimentazione e apertura che aveva spinto Alessi a creare il Centro Studi, toccava con quella prima ricerca il mondo della progettazione femminile. Con “Memory Containers” si dava voce a una parte della scena creativa che fino ad allora aveva avuto poche occasione di esprimersi nel mondo del disegno industriale.

Dal workshop nacquero 9 oggetti – “Contenitori di Memoria” – e presto se ne aggiunsero altri, superando i 15 della sfida iniziale. Le immagini dei progetti, dei riferimenti culturali e personali che li ispirarono, furono raccolti in una pubblicazione, “Rebus sic…”, insieme ai contributi di Paolo Fabbri, Lucetta Scaraffia e Franco La Cecla che parteciparono alla creazione di quel primo metaprogetto.

Il libro e i “Memory Containers” furono presentati con una grande festa organizzata nella palazzina liberty dell’Ippodromo di Milano nell’ottobre del 1991. Cuore dell’evento, una performance surreale dove una serie di personaggi bizzarri portavano in scena gli oggetti della collezione. Un momento emozionante, al quale parteciparono più di mille invitati: uno dei primi grandi eventi dedicati al design capace di coinvolgere la città.

Metaproject stories

Object

Collections

Spizziculiarity 2016

"The essential Italian food"

I always thought it was impossible to understand Italian culture without knowing its cuisine and everything that revolves around its convivial traditions. For Italians, cooking and eating are not simple actions related to survival, moments that fade somewhat anonymously into everyday life. There is always a cultural effect that accompanies the preparation and consumption of food.

Care, rapport, nutrition, tradition, values… perhaps because it’s so culturally significant, Italian food and Italians’ approach to conviviality have spread throughout the world, seducing a variety of different contexts and traditions.

This is why in 2014 I began to reflect on what I would call the truly genuine topos of Italian cuisine: pasta, pizza, coffee, ice cream… I wanted to nurture a greater appreciation of these elements, rescuing them from a certain point of view that, particularly aided by globalisation, has reduced them to folkloristic features of Italian culture, stripping them of the wealth of history and meaning that, in reality, constitutes their deepest essence.

I began this new study with a workshop dedicated to Italian ‘street food’: every region, city and village has recipes for ready-to-eat foods that can be enjoyed on the go: Neapolitan pizza, fried gnocchi in Emilia, pane e panelle or arancini in Palermo, ice cream… The examples are endless. We wanted to start from these recipes to rethink and rename them, redesigning “take away” containers for these foods that, in Italy, have a long tradition rooted in time.

The workshop, developed by students of a Korean university, led to the creation of a series of new recipes for preparing dishes for ‘snacking’—‘spizzicare’ in Italian—that are variations derived from the most typical foods particular to Italian tradition, hence the title, ‘Spizziculiarity’!

Ho sempre pensato che fosse impossibile comprendere la cultura italiana, senza conoscerne la cucina e tutto quello che ruota intorno alle tradizioni conviviali. Cucinare e mangiare per gli italiani non sono semplici azioni legate alla sopravvivenza, momenti che si dissolvono un po’ anonimamente nella quotidianità. Vi è sempre un portato culturale che accompagna la preparazione e il consumo del cibo.

Cura, relazione, nutrimento, tradizione, valori… forse proprio perché così culturalmente consistenti, la cucina e i modi del convivio italiani si sono diffusi nel mondo, conquistando contesti e usanze anche molto differenti.

È per questo che nel 2014 ho iniziato a riflettere su quelli che potrei definire dei veri e propri topos della cultura culinaria italiana: la pasta, la pizza, il caffè, il gelato… Volevo valorizzarli, ponendoli in una prospettiva diversa da quella che, soprattutto con la globalizzazione, li aveva ridotti a elementi folcloristici, avulsi da quella ricchezza di storie e significati che ne costituisce l’essenza profonda.

Iniziai questa nuova indagine con un workshop dedicato allo ‘street food’ italiano: ogni regione, città, paese ha ricette tipiche di alimenti che si consumano per strada. La pizza napoletana, lo gnocco fritto in Emilia, il pane e panelle o gli arancini di Palermo, il gelato… Gli esempi sono infiniti. Volevamo partire da queste ricette per ripensarle, rinominando e ridisegnando i contenitori per il “take away” di questi cibi che, in Italia, hanno una lunga tradizione radicata nel tempo.

Il workshop, sviluppato con gli studenti di un’università coreana, portò alla creazione di una serie di nuove ricette per la preparazione di piatti da ‘spizzicare’, declinati da quelle più tipiche e peculiari della tradizione italiana: di qui il titolo, ‘Spizziculiarity’!

Metaproject stories

Collections

Alessi in Love 2016

"Rethinking the 'token of love'. Alessi in Love, a web contest became the challenge to redesign the traditional 'Bomboniera'."

Rethinking products as a labor of love. In early 2013 a new theme to be explored started taking shape: I began reflecting on the particular item that is the ‘token of love’, a complex web of emotions, traditions and conventions. I wanted to find fresh inspiration and new usage codes for gifts of love, in all their possible forms: the object that is offered to celebrate a significant moment, that which is given to a person to declare one’s feelings or to express respect, affection and gratitude. The starting point for me was, once again, not the object itself as a mere product but mankind and our world.

With the meta-project all set, it was then necessary to organise a workshop to make it operational. I found in Desall, a platform for participatory design, the ideal partner for what I had in mind: to use an exclusively virtual contest for the selection of designers to be involved in the workshop. In August, we published the notice: anyone interested could upload their proposal for a love object on the Desall platform. We wanted to select the most interesting ones, whose designers would then be invited to the workshop.

The response far exceeded our expectations: more than 1,000 proposals were uploaded to the platform. We selected ten designers for a three-day workshop that was organised for November of that year at the premises of H-art, of which Desall was a startup. The workshop was a very intense experience and the subject matter moved the energies of all those who participated on several levels, from the design to the emotional. Not only was the area we researched completely new, it was also very complex. For this reason, the many interesting ideas that emerged from our work have required a long time to mature, so we are still in the development process of the collection.

At the same time I decided to organise a second workshop, in Bergamo, in my studio, with Antonio Aricò and Massimo Giacon. On that occasion I thought that, as a first step, we should dedicate ourselves to reinventing a classic type, the favour, known as a bomboniere in Italian. At one time or another, everyone will have received a classic, terrible favour for a wedding or christening, even from close friends and relatives. What are you supposed to do with it? Throwing it away would put you a bad mood; it would seem like you throwing away a piece of someone else’s life, someone who is dear to you. On the other hand, if you go to trade fairs for household items, it’s noticeable that in the ‘favours’ category, not a lot of effort or attention has been given to their formal research. Designing favours, therefore, presented quite a challenge, offering us the possibility to deal with a ‘no design zone’.

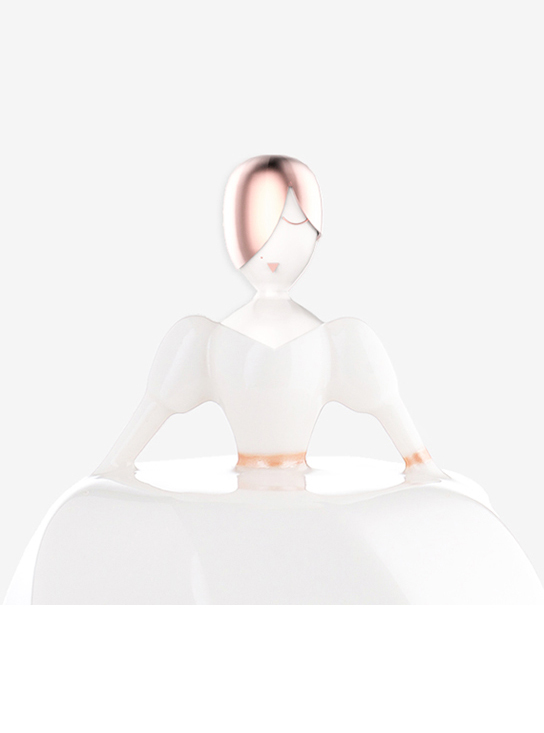

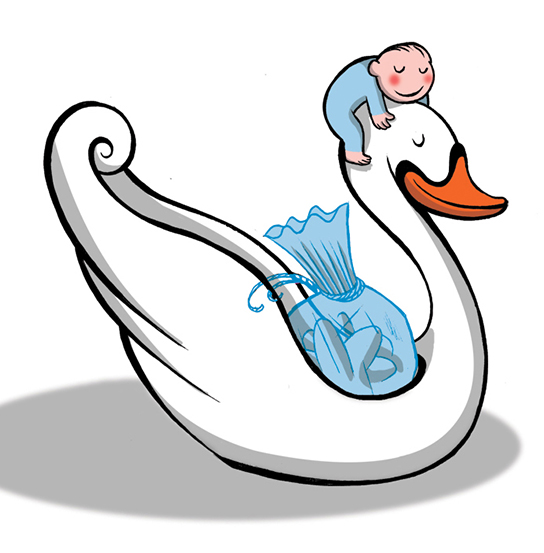

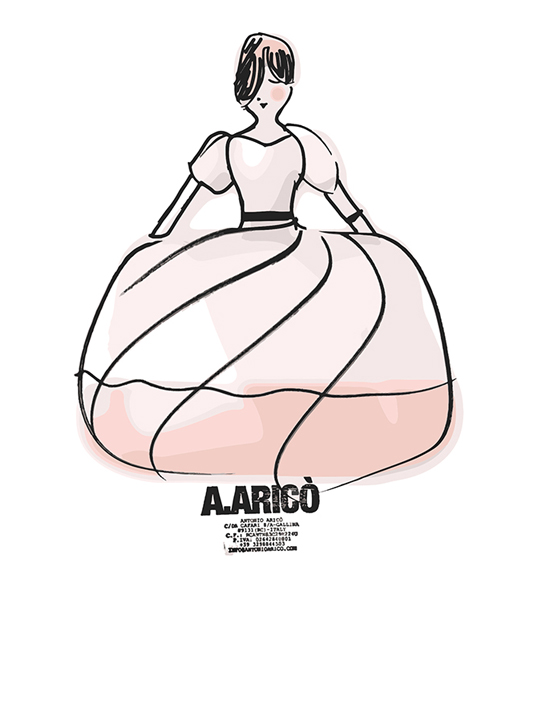

It was interesting to work on two different stylistic fronts with Giacon and Aricò. With the former I took an ironic approach, touching some classic symbols of love: the swan for weddings; the stork for the birth of a child. We played with the names of objects: Bomboniere was mixed with bamboline (dolls) and bimbo (baby) to become ‘Bomboline’ and ‘Bimboniere’ respectively. With Antonio Aricò, we moved to a different kind of imagery, exploring archetypes related to women: hospitality, the act of giving, sweetness… ‘La petite Marièe’ is an icon of timeless beauty, inspired by 18th century porcelain figurines.

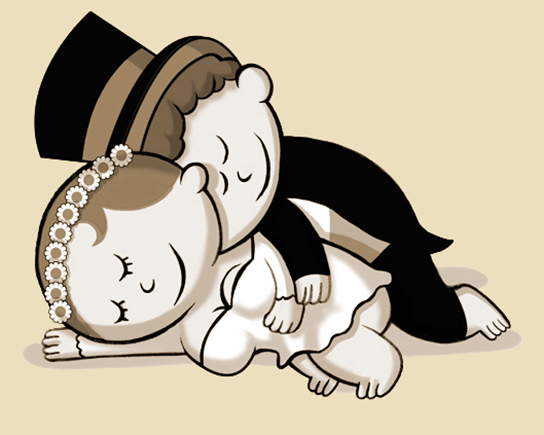

Linked to marriage there was another type that has long needed redesign: the bride and groom decoration placed atop the wedding cake, often with a bland design repeated time and time again. Giacon’s ironic and direct language led us, once again, to a completely different object: ‘Embrace me, my love.’

Ripensare il prodotto come un atto d’amore. Nei primi mesi del 2013 un nuovo tema da esplorare incominciò a profilarsi: iniziai a riflettere su quel particolare oggetto che è il ‘pegno d’amore’, una complessa trama di emozioni, tradizioni e convenzioni. Desideravo trovare nuove ispirazioni e codici d’uso per il regalo d’amore, in tutte le sue possibili declinazioni: l’oggetto che si offre per celebrare un momento significativo, quello che si dona a una persona per dichiararle i propri sentimenti o per esprimere stima, affetto, riconoscenza. Il punto di partenza per me era, ancora una volta, non l’oggetto in sé come mero prodotto ma l’uomo e il suo mondo.

Il metaprogetto era pronto, occorreva organizzare un workshop per renderlo operativo. Trovai in Desall, una piattaforma per il design partecipativo, il partner ideale per quello che avevo in mente: selezionare i designer da coinvolgere nel workshop mediante un contest esclusivamente virtuale. In agosto pubblicammo il bando: chiunque fosse stato interessato avrebbe potuto caricare sulla piattaforma di Desall la sua proposta per un oggetto d’amore. Volevamo selezionare quelle più interessanti, i cui autori sarebbero stati invitati al workshop.

La partecipazione superò di molto le nostre aspettative: sulla piattaforma furono caricate più di 1.000 proposte. Selezionammo una decina di designer per i tre giorni di workshop organizzato nel novembre dello stesso anno nella sede di H-art, di cui Desall era una startup.

Il workshop fu un’esperienza molto intensa, l’argomento mosse le energie di tutti i partecipanti su più piani, da quello progettuale a quello emozionale. Indagammo un’area non solo completamente nuova, ma anche decisamente complessa. E, proprio per questo, le molte idee interessanti emerse dal nostro lavoro, hanno richiesto un lungo tempo di maturazione, così siamo ancora nel processo di sviluppo della collezione.

In parallelo decisi di organizzare un secondo workshop, a Bergamo, nel mio studio, con Antonio Aricò e Massimo Giacon. In quell’occasione pensai che, come primo passo, avremmo dovuto dedicarci a una tipologia classica, la bomboniera e reinventarla.

Sarà capitato a tutti di ricevere durante un matrimonio o un battesimo la classica bomboniera un po’ kitsch, magari da cari amici e parenti. Che si fa? Buttarla via mette di cattivo umore, sembra quasi di buttare via un pezzettino di vita di qualcun’altro, qualcuno che ci è caro. D’altra parte, se si visita una qualsiasi fiera di oggetti per la casa, appare evidente come a questo tipo di oggetti non sia dedica una particolare ricerca formale.

La bomboniera era quindi una bella sfida, ci permetteva di affrontare una ‘no design zone’. Fu interessante lavorare su due fronti stilistici differenti con Giacon e Aricò. Con il primo ho lavorato sul piano dell’ironia, toccando alcuni classici simboli legati all’amore: il cigno, per il matrimonio, la cicogna per l’arrivo di un bambino. Abbiamo giocato anche con i nomi degli oggetti: sono nate così le ‘Bomboline’ e le ‘Bimboniere’. Con Antonio Aricò invece ci siamo mossi su un diverso immaginario, esplorando gli archetipi legati al femminile: l’accoglienza, il dono, la dolcezza… ‘La Petite Marièe’ è un’icona di bellezza senza tempo, ispirata alle damine in porcellana settecentesche.

Legata al matrimonio c’era un’altra tipologia che da tempo desideravo ridisegnare: la coppia di sposi che decora la torta nuziale, dal design spesso anonimo e ripetitivo. L’ironia e il linguaggio immediato di Giacon ci hanno portato, ancora una volta, a un oggetto completamente diverso: ‘Abbracciami amore mio’.

Metaproject stories

Collections

Centro Studi Alessi 1990

"CSA & Metaprogettare. A new approach to the act of designing based on the emotional and sensory qualities of objects"

“The rhizome connects any point to any other point, and none of its sections necessarily refer to traits of the same nature; it brings into play very different regimes of signs, and even nonsign states. Compared to centric (even polycentric) systems, to hierarchical communication and to established connections, the rhizome system is acentric, non-hierarchical and non-significant.”

Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari

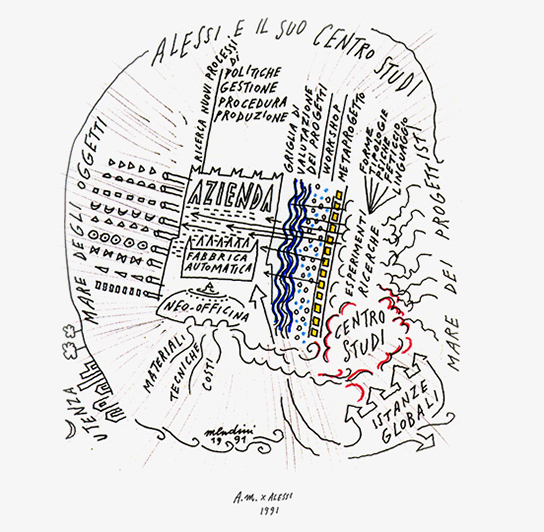

It all began in the late 80s. When the idea came about to set up a Centro Studi Alessi (Alessi Study Centre), Italian design was in a period of turmoil. It was searching for ways to escape from a notion of design that focused on the form/function polarity, seeking a hybridasation based on the emotional and sensory qualities of objects.

Along with Alessandro Mendini, Alberto Alessi designed the centre as a place where research and experimentation could be developed freely. I was asked to direct this laboratory of sorts, with the idea of pushing the world of Alessi towards a methodological approach that was to be as innovative as possible. I was curious about the company’s dual soul: it was still highly traditional, but at the same time, it was driven by what might be described as a great love for the adventure of design.

We inaugurated the Centro Studi Alessi in 1990. From the beginning, the work was guided by a double-faceted mission. On the one hand, to elaborate theoretical contributions on topics related to the field of objects. These reflections would go on to guide the company’s research, creating an important body of content that was presented through books, which were published quite regularly at the time. On the other hand, to create a new process, an incubator, for working with young people or new designers. Up to that point, the company had only worked with “grand masters” and Alberto Alessi wanted to address the young world of design that was emerging.

“Laura brought to Alessi the intuition and background of a semiologist who had studied under the tutelage of such important scholars as Umberto Eco and Paolo Fabbri. She often reminds me of Marianne Brandt, who in the twenties was the first woman to work in the Bauhaus Metallwerkstatt. Together with her, we began the painstaking process of freeing Alessi from the quagmire of rhetoric that had bogged down certain schools of thought in Italian design at the time. Through her, Alessi’s work flow experienced the introduction of disciplines that had until then remained outside the process, such as anthropology and semiotics.” Alberto Alessi

Studies in semiotics and the research carried out up till then were a great help to me, as were my experiences in entertainment and contemporary dance, which had particularly cultivated the ability to develop creative work in teams. I learned how to explore a narrative of ideas and concepts based on similarities and harmonies between different personalities, consisting of continuous meetings and discussions, summary and review. Teamwork, understood in these terms, became a characteristic of the design developed by the Centro Studi Alessi.

“Metaprogettare” (to meta-design). This word harbours a new way to approach the act of designing. The suffix “meta-” comes from the Greek “to go beyond”. For me the challenge was to overcome the limitations and constraints that generally presided over design. I began to build a different approach based on the creation of a vision, of a context that would encourage dialogue between disciplines involving a variety of professionals around a certain topic. A topic that wasn’t necessarily dictated by a practical need, rather by needs that were more subtle, emotional, affective… This vision gave rise to stimuli and suggestions for designing objects that could enter into a relationship with people, no longer just products, but presences that were in a sense animated, characters in little domestic stories.

”Il rizoma collega un punto qualsiasi con un altro punto qualsiasi, e ciascuno dei suoi tratti non rimanda necessariamente a tratti dello stesso genere, mettendo in gioco regimi di segni molto differenti ed anche stati di non-segni. Rispetto ai sistemi centrici (anche policentrici), a comunicazione gerarchica e collegamenti prestabiliti, il rizoma è un sistema acentrico, non gerarchico e non significante.”

Gilles Deleuze e Félix Guattari

Tutto iniziò alla fine degli anni ’80, l’idea di un Centro Studi per Alessi si sviluppò in un periodo di fermento per il design italiano: si ricercava una via di fuga dal progettare inteso all’interno della polarità forma-funzione, verso un’ibridazione attraverso le qualità emotive e sensoriali degli oggetti.

Insieme ad Alessandro Mendini, Alberto Alessi ideò il progetto di un luogo dove sviluppare in modo molto libero ricerca e sperimentazione. Mi proposero di dirigere questa sorta di laboratorio, con l’idea di spingere il mondo Alessi verso un approccio metodologico quanto più innovativo possibile. Mi incuriosiva la duplice anima dell’azienda: ancora fortemente tradizionale, ma al tempo stesso mossa da quello che potrei descrivere come un grande amore per l’avventura progettuale.

Inaugurammo il Centro Studi Alessi nel 1990. Fin dall’inizio il lavoro fu guidato da una duplice missione. Da un lato, elaborare contributi teorici su temi legati all’oggetto, riflessioni che poi avrebbero orientato la ricerca dell’azienda e creato importanti contenuti presentati nei libri che allora pubblicava con una certa regolarità. Dall’altro, creare un nuovo processo e un incubatore per lavorare con giovani o nuovi designer. Fino ad allora l’azienda aveva collaborato soltanto con i “grandi maestri” e Alberto Alessi desiderava confrontarsi con il mondo del giovane design emergente.

“Laura ha portato in Alessi l’intuizione e la formazione di semiologa acquisita alla scuola di Eco e di Fabbri. Spesso mi ricorda Marianne Brandt, la prima donna che ha lavorato negli anni venti nella Metallwerkstatt del Bauhaus. Con lei è iniziato il faticoso processo per far uscire la Alessi dalle remore della retorica in cui si beava un certo paludato design italiano. Tramite lei abbiamo introdotto in Alessi discipline fino ad allora rimaste estranee, come l’antropologia e la semiologia.” Alberto Alessi

Gli studi in semiotica e le ricerche svolte fino ad allora mi furono di grande aiuto, come le esperienze fatte nel mondo dello spettacolo e della danza contemporanea, in particolare la capacità di sviluppare un lavoro creativo in team. Avevo imparato come esplorare un immaginario attraverso un lavoro basato sulle affinità e le sintonie fra personalità diverse, fatto di continui incontri e confronti, di sintesi e revisioni. Il lavoro in team inteso in questi termini divenne caratteristica peculiare della progettazione sviluppata dal Centro Studi Alessi.

“Metaprogettare”, in questa parola il nuovo modo di affrontare il progetto. Il suffisso meta- deriva dal greco “andare oltre”: per me la sfida era quella di superare i limiti e i vincoli che generalmente presiedevano la progettazione. Iniziai a costruire un diverso approccio basato sulla creazione di un immaginario, di un contesto dove far dialogare più discipline, coinvolgendo figure professionali diverse attorno a un tema. Un tema non dettato da un’esigenza pratica, ma da bisogni più sottili, emozionali, affettivi… Da questo immaginario nascono gli stimoli e le suggestioni per progettare oggetti in grado di entrare in relazione con le persone, non più semplici prodotti, ma presenze in un certo senso animate, personaggi di piccole storie domestiche.

Metaproject stories

Collections

The Urban Fetish 1990

"The fetishisation of objects. The artistic experimentation at the beginning of Centro Studi Alessi"

The origins of a journey can sometimes be encompassed in an encounter, at times by chance… an unpredictable alchemy. In the early 90s, Alessi wanted to open a Study Centre. The genesis of this new place for research and experimentation originated from one such spontaneous encounter, from an unexpected fusion of distant contexts. Here’s what happened.

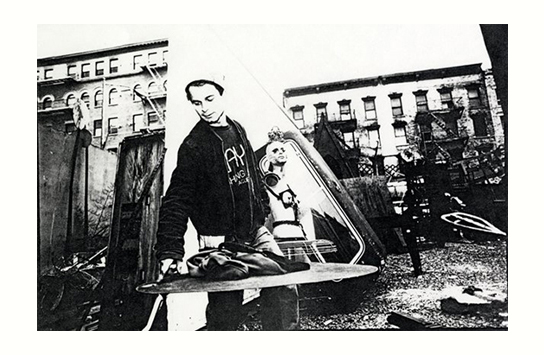

In 1989 I developed a reflection on the art and culture of sub-Saharan Africa. In particular, the sculptures and everyday objects of the natives interested me. In December of that same year, I went to Washington DC to further my research at the Smithsonian - National Museum of African Art. From there I went on to New York where, in January 1990, I had an important encounter. A journalist friend of mine, Luca Neri, introduced me to a group of East Village artists who, although operating independently, were collectively called “Trash designers”.

Steiner Arnerich, Linus Coraggio, Alex Locadia, and Luca Pizzorno created works with what the streets offered. The use of waste materials and discarded objects gave rise to sculptures that interpreted the reality around them. A very similar process occurred in African and primitive civilisations, where the totem and ritual objects were created with what the surroundings, in this case Nature, had to offer.I immediately understood the similarity between the two contexts. It was a awareness I had developed during college, also thanks to encounters with teachers such as Francesca Alinovi, a prominent activist in operations carried out in the 80s by Black Graffiti.

So, following this parallelism, I undertook an experiment with the Trash designers that led to a series of works: “urban fetishes”. Feitiço is the term by which the Portuguese navigators of the sixteenth century called idols and amulets used by indigenous peoples in Africa: the fetish is an inanimate object which is given a magical or spiritual power.

“The fetishisation of objects from other cultures is a work of contextualisation that changes their meaning [...] it becomes fetish that which represents the singularity, exoticism, the unexpected, objects discovered by chance or coincidence (l’objet trouvé, but also the ready made from another culture).” Franco La Cecla

Each Trash designer was working in his own technique: using scrap metal, assembling waste plaster castings, welding pieces of rusty or molding leather strands.This investigation culminated in an exhibition we held in Milan. It did not lead to any products, it was a pure artistic experimentation. It did, however, usher in a reflection on objects that would become the core of work carried out by the Centro Studi Alessi: objects as a medium of relationship, “animated”, bearers of cultural and emotional value.The journey that had begun with the Trash designers continued in the following months in Paris — with Doury Pascal and Jean-Louis Floch — and Milan — with Lorenzo Mattotti and Louise Gibbs.

Alessi’s “Fetish object” became a symbol, a guideline. It defined an approach that continued in subsequent metaprojects, charting out the territory that Alessi would explore in its own research on relational, affective and playful objects.

L’origine di un percorso a volte è racchiusa in un incontro, anche casuale… un’imprevedibile alchimia. All’inizio degli anni ’90 Alessi desiderava aprire un Centro Studi. La nascita di questo nuovo luogo di ricerca e sperimentazione ebbe origine da uno di questi incontri spontanei, da un’inaspettata fusione tra contesti lontani. Ecco cosa accadde.

Nel 1989 sviluppai una riflessione sull’arte e la cultura dell’Africa sub sahariana, m’interessavano in particolare le sculture e gli oggetti d’uso indigeni. Nel dicembre di quell’anno andai a Washington DC per approfondire la mia ricerca allo Smithsonian - National Museum of Africa Art e da lì proseguii per New York dove, nel gennaio del 1990, feci un incontro importante. Un amico giornalista, Luca Neri, mi presentò un gruppo di artisti dell’East Village che, sebbene operassero autonomamente, venivano collettivamente chiamati “Trash designers”.

Steiner Arnerich, Linus Coraggio, Alex Lokadia, e Luca Pizzorno, creavano opere con ciò che la strada offriva, usando materiali di scarto e oggetti in disuso davano vita a sculture che interpretavano la realtà che li circondava. Un processo molto simile avveniva nelle civiltà africane e primitive, dove i totem e gli oggetti rituali erano creati con quanto l’ambiente circostante, in quel caso naturale, metteva a disposizione.

Colsi subito la similitudine tra i due contesti, era una sensibilità che avevo sviluppato durante l’università, anche grazie all’incontro con docenti come Francesca Alinovi, artefice negli anni ’80 dell’operazione dei Black Graffiti.

Così, seguendo quel parallelismo, intrapresi con i Trash designers una sperimentazione che portò a una serie di opere, di “feticci urbani”. Feitiço è il termine con il quale i navigatori portoghesi del XVI secolo chiamavano gli idoli e gli amuleti usati dai popoli indigeni africani: il feticcio è un oggetto inanimato al quale è attribuito un potere magico o spirituale.

“La feticizzazione degli oggetti di altre culture è un’opera di decontestualizzazione che ne muta il significato […] diventa feticcio ciò che rappresenta la singolarità, l’esoticità, l’inatteso, il rinvenuto per caso o per coincidenza (l’objet trouvé, ma anche il ready made proveniente da un’altra cultura).” Franco La Cecla

I Trash designers lavorarono ognuno con la propria tecnica: utilizzando scarti in metallo, assemblando rifiuti in colate di gesso, saldando pezzi di ferro arrugginiti o modellando fili di cuoio.

La ricerca si concluse con una mostra che realizzammo a Milano. L’operazione non portò a dei prodotti, fu una pura sperimentazione artistica, ma inaugurò quella riflessione sull’oggetto che sarebbe diventata il cuore del lavoro sviluppato dal Centro Studi Alessi: oggetti come medium di relazione, “animati”, portatori di un valore culturale ed emotivo.

Il percorso intrapreso con i Trash designers proseguì nei mesi successivi a Parigi – con Pascal Doury e Jean-Louis Floch – e a Milano – con Lorenzo Mattotti e Louise Gibbs.

“L’oggetto feticcio” Alessi divenne un simbolo, una linea guida. Definì un approccio che continuò nei metaprogetti successivi, segnando quel territorio proprio della ricerca di Alessi sull’oggetto relazionale, affettivo e ludico.