Story

“L’Officina Alessi” Book

Story

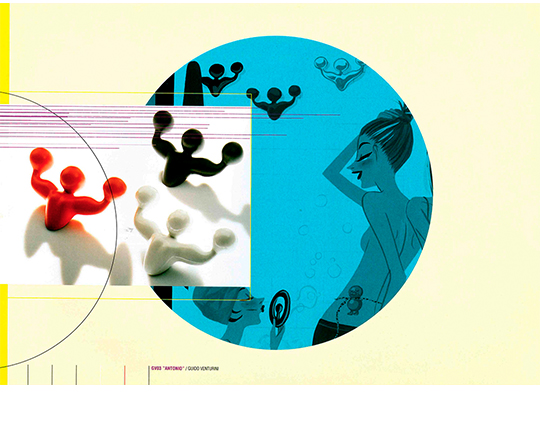

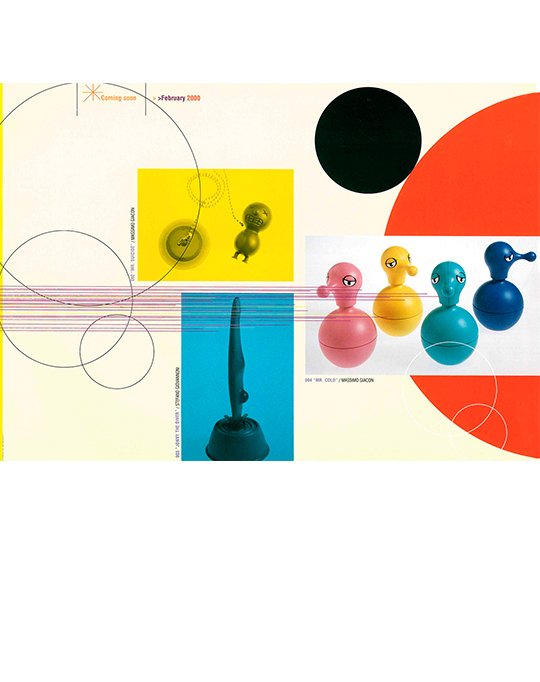

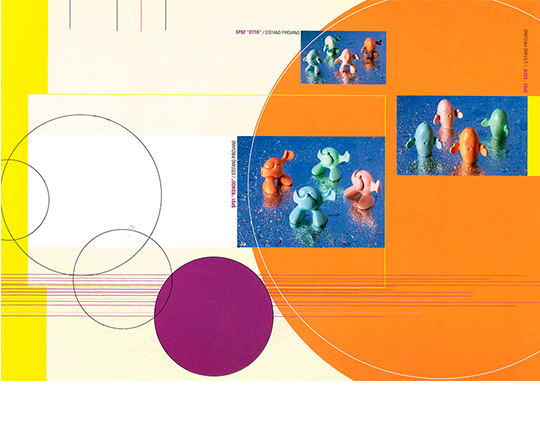

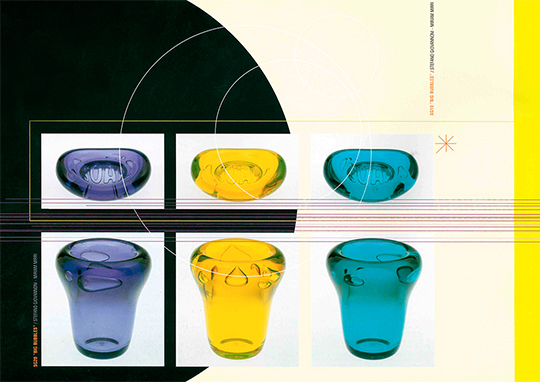

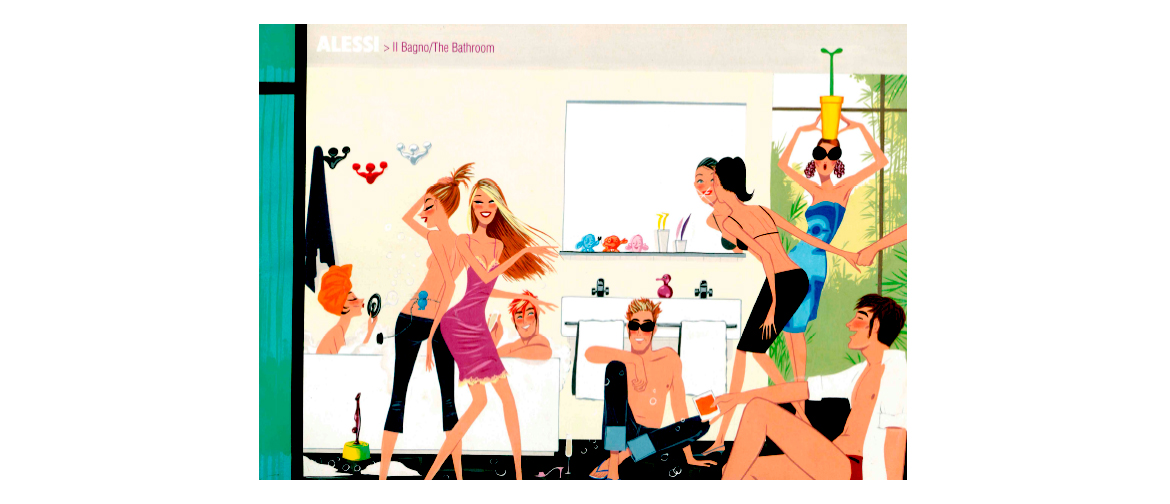

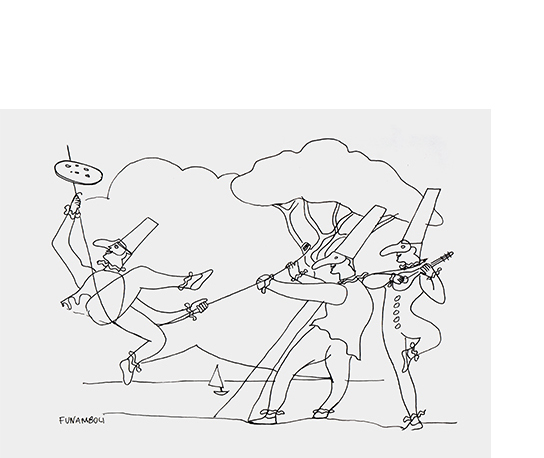

“Here the Catalogue” Illustrated by Jordi Labanda 1999

“Here the Catalogue”

Catalogue for The Bathroom and the floating objects illustrated by Jordi Labanda in 1999.

Story

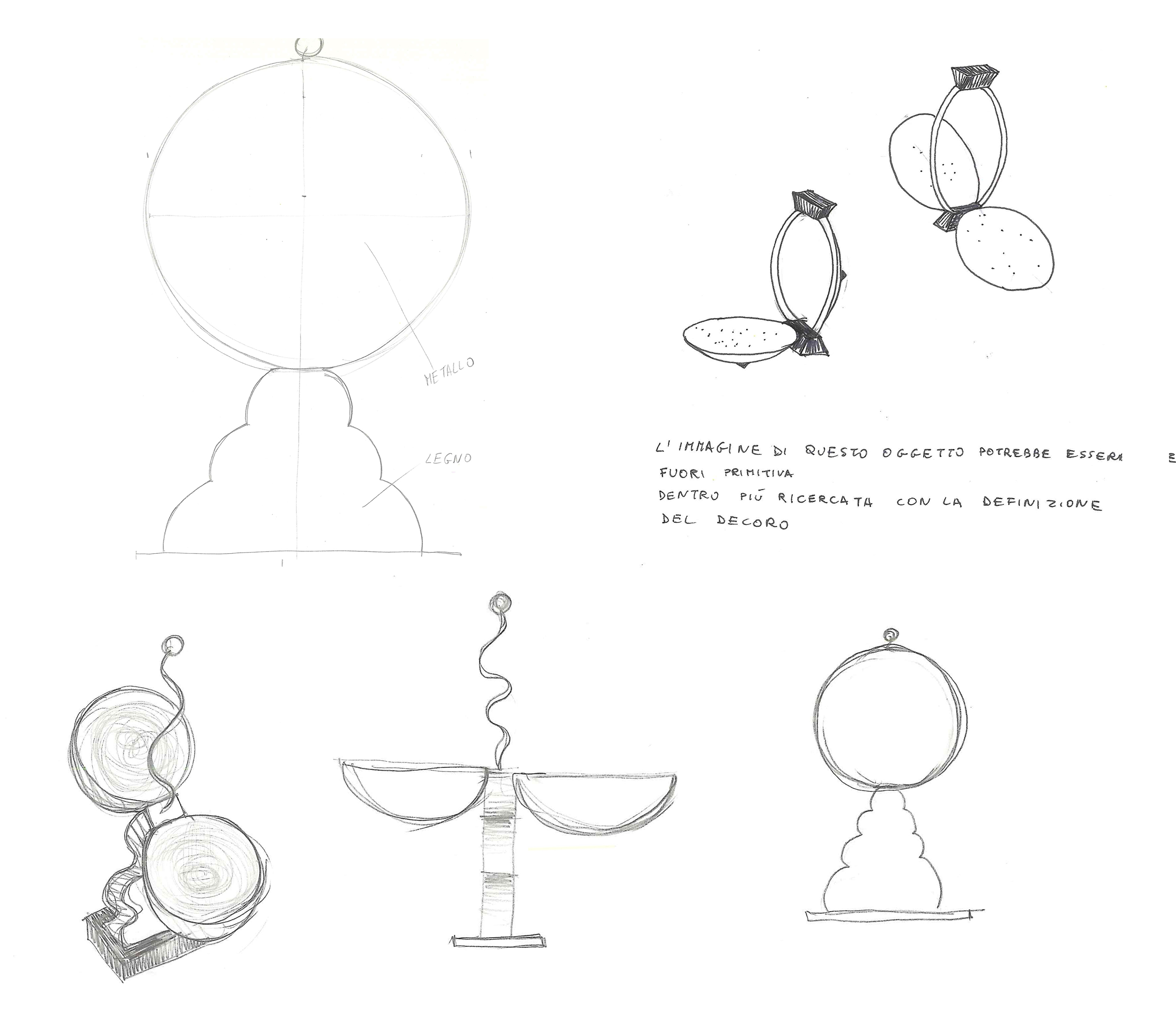

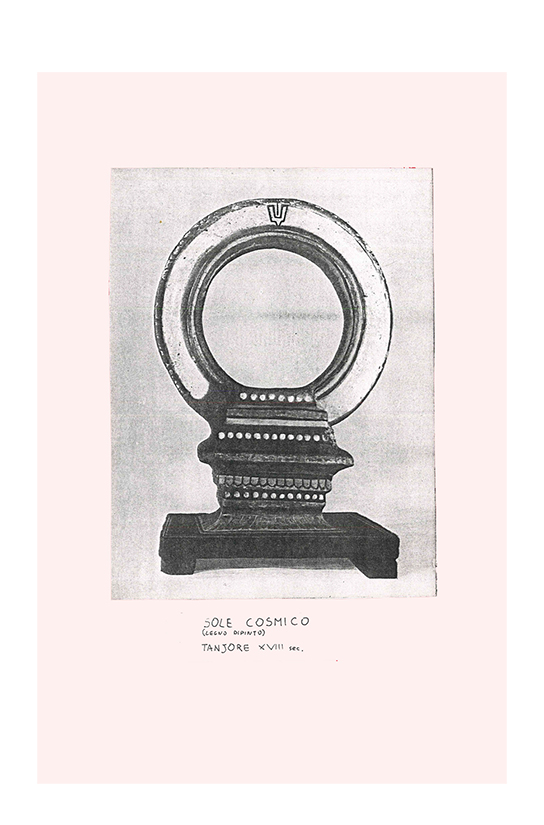

F.F.F. Book

Story

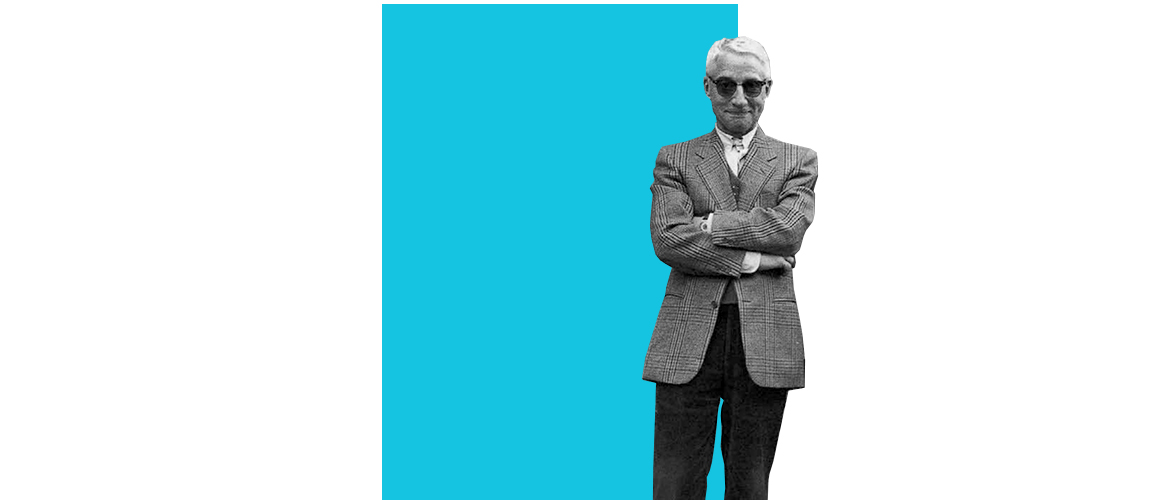

Mendini’s Future

13/04/2016

Refined designer or provoker wearing surgeon’s gloves? Alessandro Mendini escape definition, constantly moving towards a brilliant and unreachable elsewhere.

In 2000, the first issue of the experimental magazine “Due” published Marcello Jori’s memorable account of his talk with Alessandro Mendini. Among the many topics discussed are a few reflections of eternal interest…

Marcello Jori. Dear Alessandro, I was at University when I first heard about you. It was about your generosity towards your aides. In a few years I had met almost all of them, and I began to see Mendini as a galaxy of luminous aides. They would often open their wallets to show your picture. They spoke of you with respect tinged with affection.

High spirits surrounded those individuals, trust in their instructor, an Athenian love.

Thus for me, generosity became one of the forms of your style. Can generosity be considered as one of the ingredients in an artist’s project?

Alessandr Mendini. It seems to me the generosity follows the movement of a pendulum: every time you give, some other form of generosity, or some other form of energy, comes back to you. Closure doesn’t allows ideas to pass from one person to another, nor does it allow people’s voices to mix. Making art today is also a mirror game. And maybe generosity is one of the forms of an artist’s narcissism: one gives because of anxiety to receive. I’ve always preferred to listen rather than to speak .

M. J. In respect to the beginning of this century, the average person’s life today is about thirty years longer. As a result the youth of an artist is prolonged, running into the stage of maturity. Can we speak today of “young maturity”? Do you think that such a definition adequately describes your current situation?

A. M. For many years now my work has been formulated on this groundwork: on one hand a “static” reference to the primordial feelings of humanity, on the other a “dynamic” method of accepting new visual aspects of the world. I don’t know if that’s a formula, but it’s the way in which I carry out my ideational activities regardless of age.[…]

M. J. If you were to edit a “Mendini” dictionary, how would you write the definitions for “artist”, “architect”, “designer”, “writer”? And the definitions for “feeling”, “sympayhy”, “emotion”, “pain”, “joy”, “serenity”?

A. M. I wouldn’t be able to edit my own dictionary. You mentioned terms which are certainly all important for me, some linked to my daily work, others which define my most far off mirages. However, you forgot another word that is very important to me: the word “workman”. I feel that I am labourer, a workman.

M. J. In our last meeting I found you intent on an operation of “aesthetic cleaning”. With the responsible melancholy of a man who must leave the century most cram-packed with inventions carrying only one suitcase, you where choosing those objects having sufficient dignity to deserve to be farried into the third millennium.

Did you succeed in finishing this difficult mission?

A. M. When you’ve worked and produced a lot, a great lot, on countless beautiful, ugly, arid, muddy or sunny roads, you definitely find your purity encrusted and worn-down by tiredness and by infinite and excessive opposing experiences…keeping our humanity limpid and our project fresh is so difficult, it’s not only my task but everyone’s…The millennium aides practice of such redeeming gymnastics, but keeping one’s thought slow and reinvigorated is not so easy.

Designer raffinato e provocatore in guanti chirurgici? Alessando Mendini fugge da ogni definizione spostandosi sempre verso un altrove brillante e irragiungibile …

Nel 2000, in occasione della pubblicazione del primo numero della rivista sperimentale “Due”, Marcello Jori condusse un’indimenticabile intervista ad Alessandro Mendini. Tra i molti pensieri scambiati, alcuni penso abbiano un interesse fuori dal tempo…

Marcello Jori. Caro Alessandro, frequentavo l’università quando ho avuto la prima informazione su di te. Riguardava la tua generosità verso i collaboratori. In qualche anno li conobbi quasi tutti e per me Mendini diventò una costellazione di collaboratori luminosi. Ti portavano sempre in tasca. Spesso aprivano il portafoglio e mostravano la tua fotografia. Parlavano di te con stima venata di affetto. Vorticava buon umore su quelle persone, fiducia nel maestro, amore di stampo ateniese. Così la generosità divenne una delle forme del tuo stile. Si può considerare la generosità fra gli ingredienti di un progetto d’artista?

Alessandr Mendini. La generosità mi sembra segua le mosse di un pendolo: ogni volta che dai, ti torna indietro altra generosità, altra energia. Le chiusure non fanno passare le idee da uno all’altro, e non mescolano i respiri delle persone. Fare arte oggi è anche un gioco di specchi. E forse la generosità è una delle forme del narcisismo dell’artista: uno dà perché è ansioso di ricevere. A me è sempre piaciuto più ascoltare che parlare.

M. J. Rispetto all’inizio del secolo, la durata media della vita di un uomo contemporaneo si è alzata di almeno trent’anni. Di conseguenza la giovinezza di un artista si protrae più a lungo, invadendo la fase della maturità. Si può parlare oggi di “giovane maturità”? Pensi che questa definizione sia adatta a rappresentare la tua condizione attuale?

A. M. Da tanti anni il mio lavoro è impostato su questa base: da un lato il riferimento “statico” ai sentimenti primordiali dell’umanità, dall’altro il metodo “dinamico” nell’accettare le novità visuali del mondo.

Non so se questa è una formula, ma è il modo di condurre l’attività ideativa indipendentemente dall’età.

M. J. Se dovessi curare un dizionario “Mendini”, come compileresti alle voci “artista”, “architetto’, “designer”, “scrittore”? E alle voci “sentimento”, “commozione”, “emozione”,”dolore”, “gioia”,

“serenità”?

A. M. Non sarei in grado di compilare un dizionario di me stesso. Certo, tu citi termini che per me sono tutti importanti, alcuni legati al mio lavoro quotidiano, altri che definiscono i miei miraggi più lontani.

Hai dimenticato però un’altra parola per me importante: la parola “operaio”. Io mi sento anche un lavoratore, un operaio.

M. J. Nel nostro ultimo incontro ti ho trovato intento a un’operazione di “pulizia estetica”. Con la responsabile malinconia di un uomo che deve abbandonare il secolo più stipato di invenzioni con una valigia soltanto, stavi selezionando quegli oggetti dotati di tale dignità da meritare di essere traghettati nel terzo millennio. Sei riuscito a concludere la difficile missione?

A. M. Quando uno ha lavorato e generato tanto, tantissimo, muovendosi su innumerevoli strade belle e brutte, aride, fangose o assolate, certamente trova la sua purezza incrostata e logorata da stanchezza e da infinite e troppe opposte esperienze… Mantenere limpida la nostra umanità e fresco il nostro progetto è così difficile, è un compito non solo mio, ma proprio di tutti… Il millennio favorisce l’esercizio di questa ginnastica liberatoria, ma tenere lento e ossigenato il pensiero non è cosa facile.

Story

The Catalogue Alessi Bambino 2003

Story

Fiabe 2013

Stories

Story

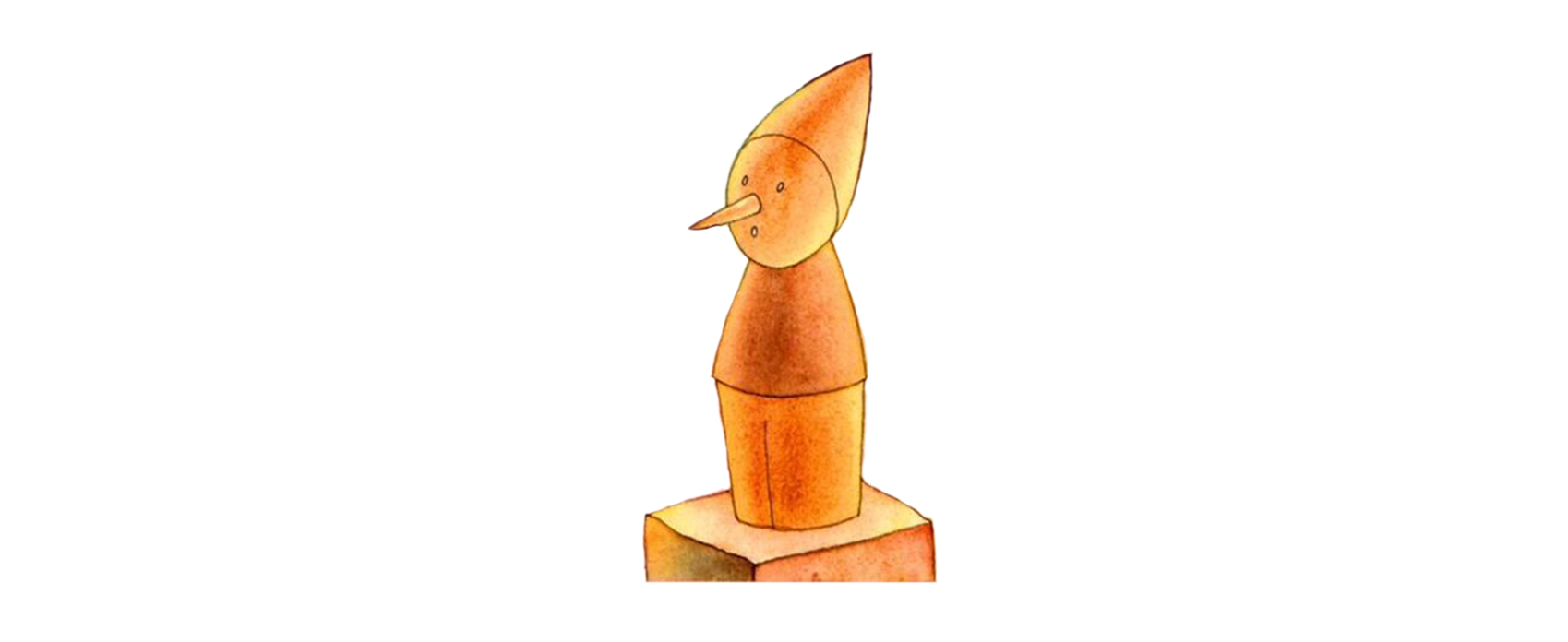

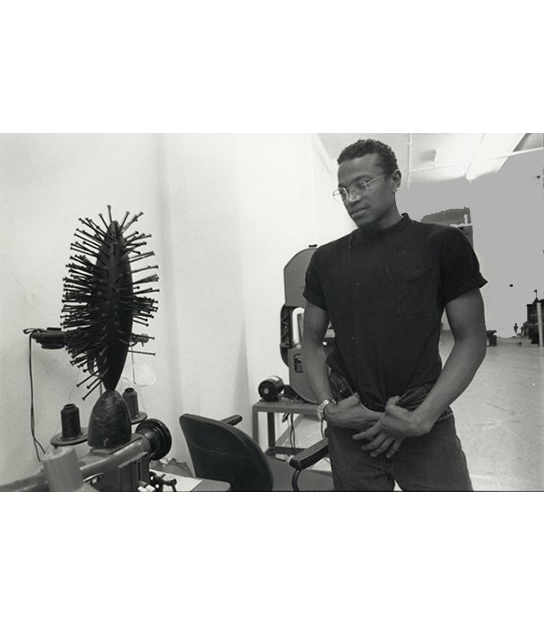

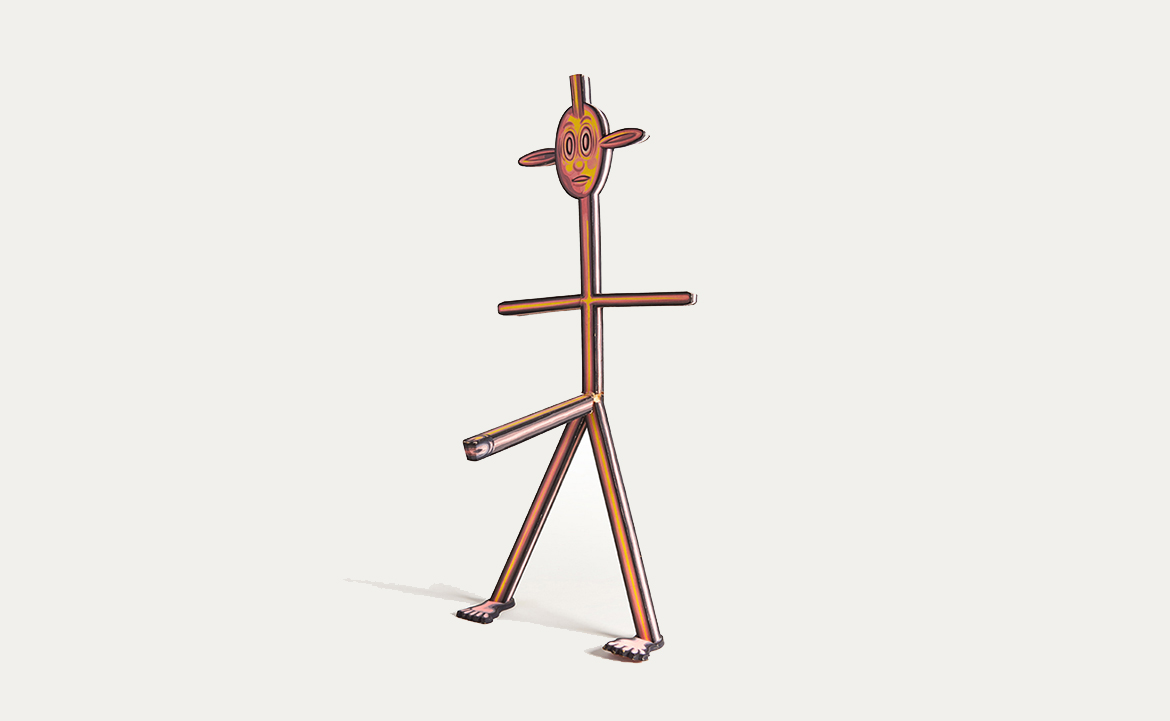

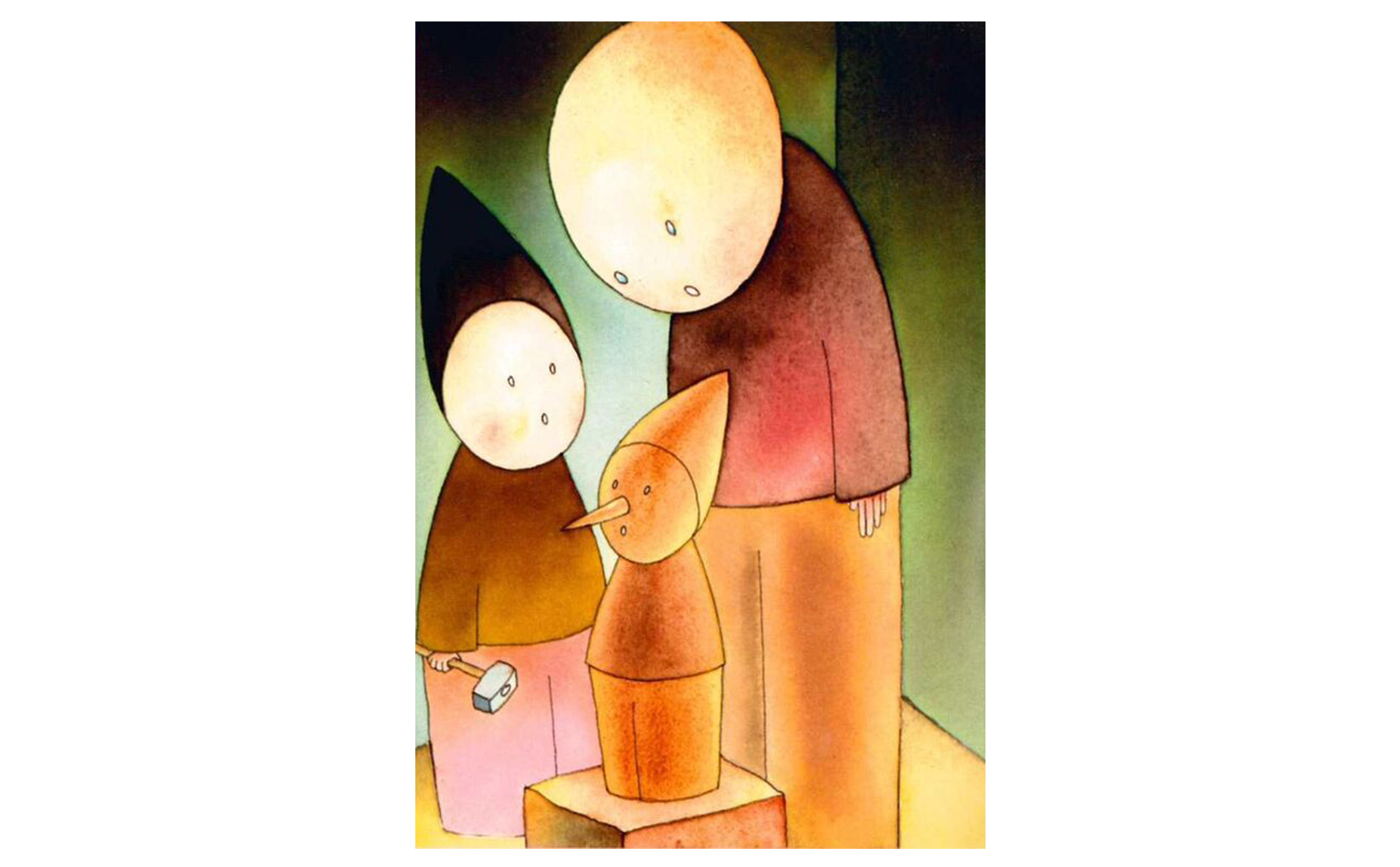

Pinocchietto di Jori

27/03/2016

The day Pinocchio became a boy, Geppetto nearly died with happiness. Nearly, I said, because luckily he lived a little while longer. Enough time to invent another dream for himself and to ask the blue-haired Fairy to make it come true.

“You again?” said the Fairy disappointed. “Was it not enough for you that a piece of wood become a real boy?”

“No!” answered Geppetto, who had become very hard to please. “Now I want my Pinocchio to go to college and to get a degree.”

“No…and NO!” said the Fairy, and Geppetto suddenly died from the pain.

Pinocchio cried for a solid month and was inconsolable for three years. Then, at the age of nineteen, to honour the memory of his father, he decided to become a carpenter. And do you know what the first thing he made was? Something wooden, you’d think, maybe a table or a chair or a cuckoo clock… Oh no! He made another puppet and he called it “Pinocchietto,” that is little Pinocchio.

Soon afterwards he was bothering the Fairy again, begging het to bring the puppet to life.

“I’ve had enough of you carpenters!” she was angry again.

“If you want children have them with women like everyone else!” she said finally and flew away.

Pinocchio cried for a couple of hours in front of his wooden son, but then he smiled at an idea that came in to his head.

He won’t live, he thought, but he is so nice that he makes me happy.

Suddenly the door of the workshop opened and a distinguished-looking gentleman with blue eyes entered.

“Hello, my name is Master Alessi. They tell me that that you are a carpenter…”

“That’s me!” he said proudly.

“And where are your wares?” asked the gentleman.

“Here!” exclaimed Pinocchio showing him the lifeless wooden child with pride.

“But what is it for?” he replied. He was a very practically-minded man.

“It makes people happy,” Pinocchio said.

Master Alessi examined the object more carefully and he began to smile.

“I’ll buy it!” he said “Make me some more, no, make me lots more, so I will be able to make a load of people happy.”

Marcello Jori

Il giorno in cui pinocchio diventò un bambino, Geppetto quasi morì dalla felicità. Quasi, dico, perché per fortuna visse ancora un po’. Abbastanza da inventarsi un altro sogno e chiedere alla fata turchina di realizzarlo.

“Ancora tu?” Disse la fatina piuttosto contrariata.

“Non ti è bastato che un pezzo di legno sta diventando un bambino vero?”

“No!” rispose Geppetto diventando ormai incontentabile. “Ora vorrei che il mio Pinocchio andasse all’università e diventasse dottore.”

“No e poi no !” ribatté la fatina e, dal dolore, Geppetto morì all’istante.

Pinocchio pianse un mese intero e si disperò per tre anni. Poi, all’età di diciannove, per fare onore al babbo, decise di diventare falegname come lui. E sapete cosa fece come prima cosa? Un oggetto di legno, penserete voi, magari un tavolo, una sedia, un orologio a cucù…

Nossignori! Fece un altro burattino e lo chiamò Pinocchietto.

Subito dopo scomodò di nuovo la fata turchina e la pregò di farlo diventare vivo.

“È ora di finirla con voi falegnami !” Si arrabbiò di nuovo. “Se volete dei bambini, fateli con le donne come tutti gli altri!” Concluse e volò via.

Pinocchio pianse un paio d’ore davanti al suo povero figliolo di legno, ma poi lo guardò e sorrise perché gli era venuto proprio carino.

Non sarà vivo, pensò, ma è talmente simpatico che dà vita a me!

All’improvviso si aprì la porta della bottega ed entrò un distinto signore con gli occhi celesti.

“Buongiorno, sono Mastro Alessi. Mi dicono che lei è un falegname…”

“Certo!” esclamò orgoglioso.

“E dove sono le cose di legno?” Aggiunse quell’uomo.

“Ho fatto questo” Esclamò Pinocchio mostrando i figlio senza vita.

“Ma a cosa serve?” Ribatté il signore che apprezzava solamente le cose utili.

“A fare contenti.” Se ne uscì Pinocchio.

Mastro Alessi guardò meglio l’oggettino e gli venne da sorridere.

“Lo compro!” disse. “Me ne faccia tanti, anzi tantissimi, così farò contenta un sacco di gente”.

Marcello Jori

Stories

Story

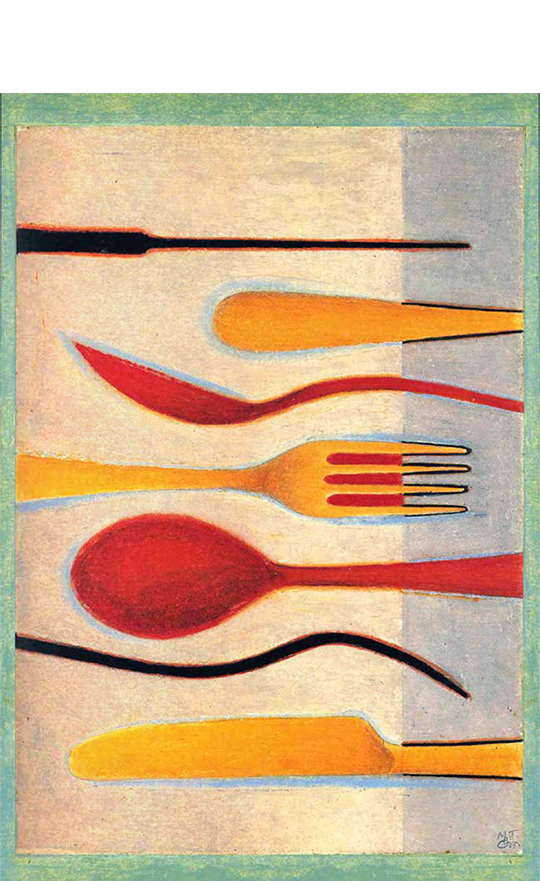

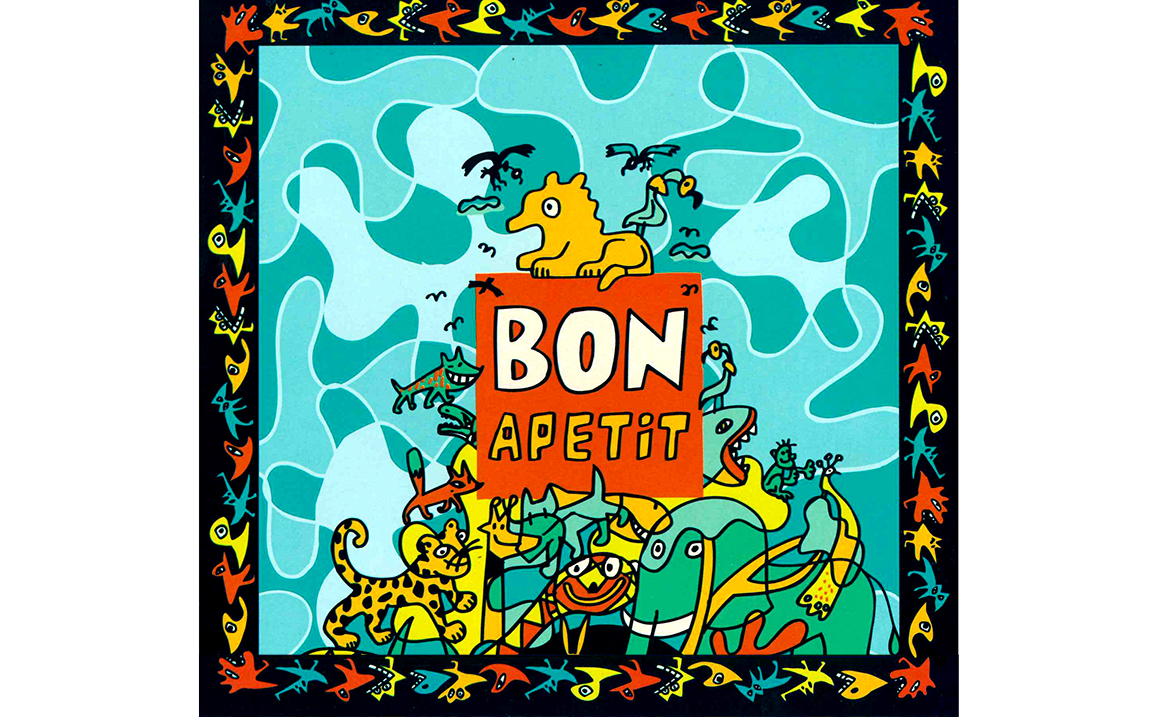

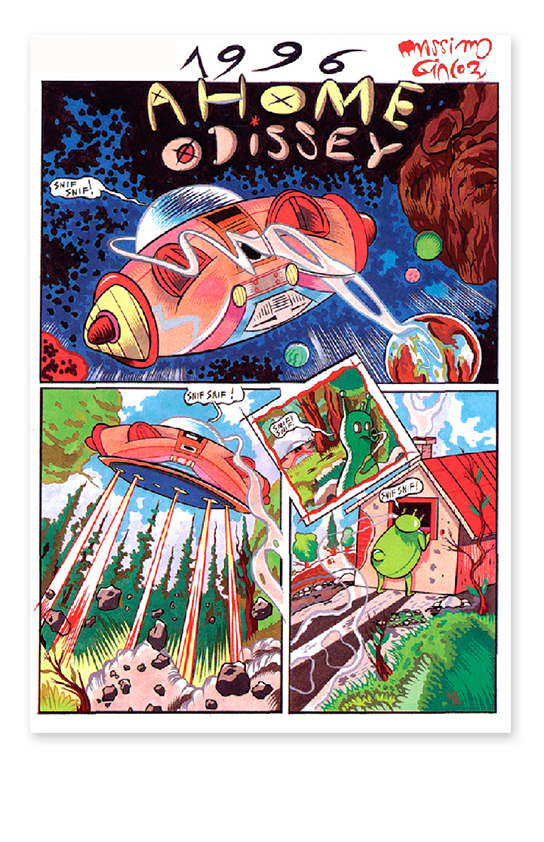

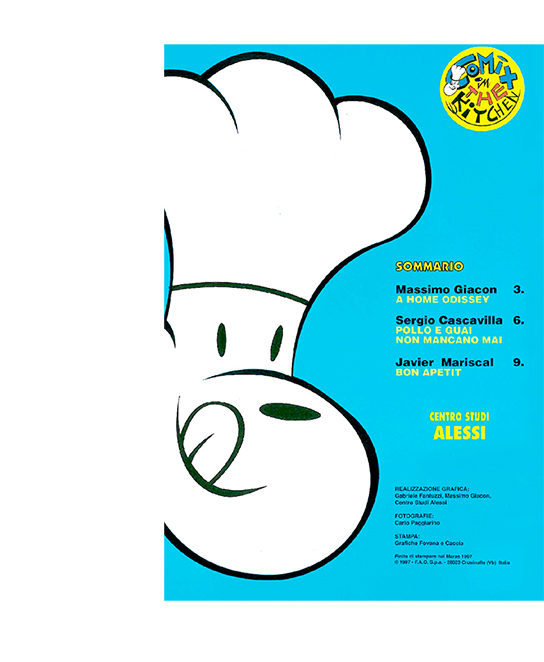

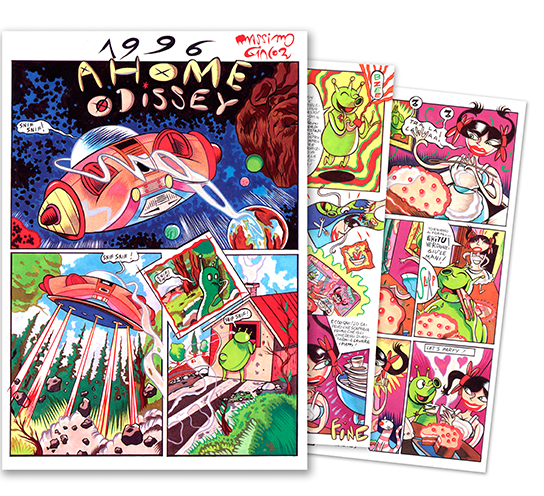

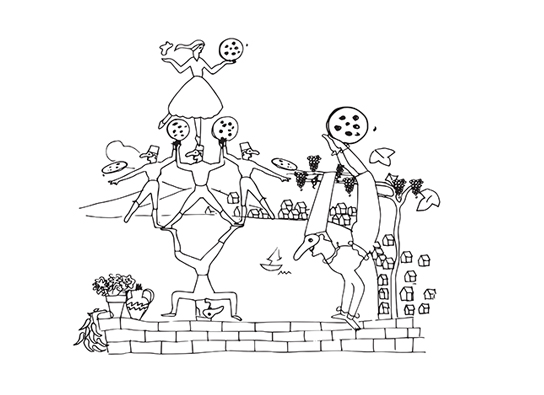

Comix in the Kitchen 1997

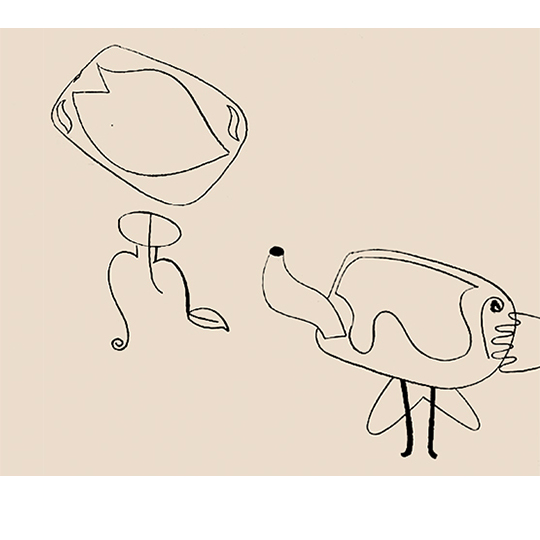

Design objects are born from a creative process where knowledge and a variety of skills converge. I always thought that it’s not to simply have the correct application of functional, aesthetic, production and sales criteria: an object must be born in the most natural way possible by the contact of cultures, knowledge, different techniques and aesthetic inspirations. Inspiration can come from comics as well as it can from biology. My job is to have different forces interact, mix different kinds of knowledge, find new creative ideas and their possible application.

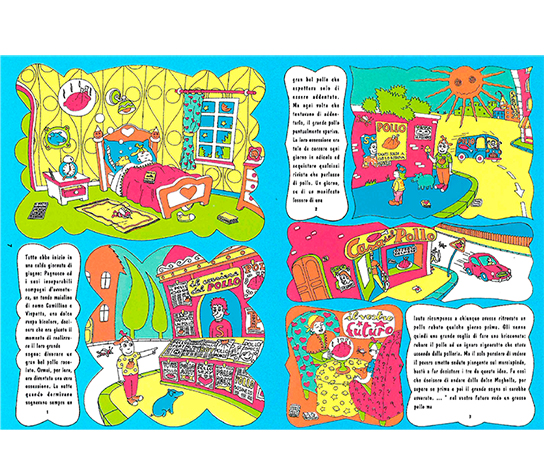

With “Comix in the Kitchen” the language of comics he entered the world of kitchen items. Three designers were involved in this new design game: Massimo Giacon, Sergio Cascavilla and Javier Mariscal. The came out of the desire to deal with “no design areas.” Aprons, tea towels, oven gloves are generally very visible in our kitchens, thus becoming furnishing elements, parts of that particular domestic landscape. But up until then, no one had dedicated themselves to their design through proper research formal.

Thanks to Giacon, Cascavilla and Mariscal, these objects — along with trays, placemats and napkins — became surfaces to bring to life opportunities for the creation of a scenario or a mini-story. The idea was to invent characters and narratives, a landscape in which the three designers would feel at home in a familiar context even though they were confronted with designing a collection of objects; a completely different job than creating comic books.

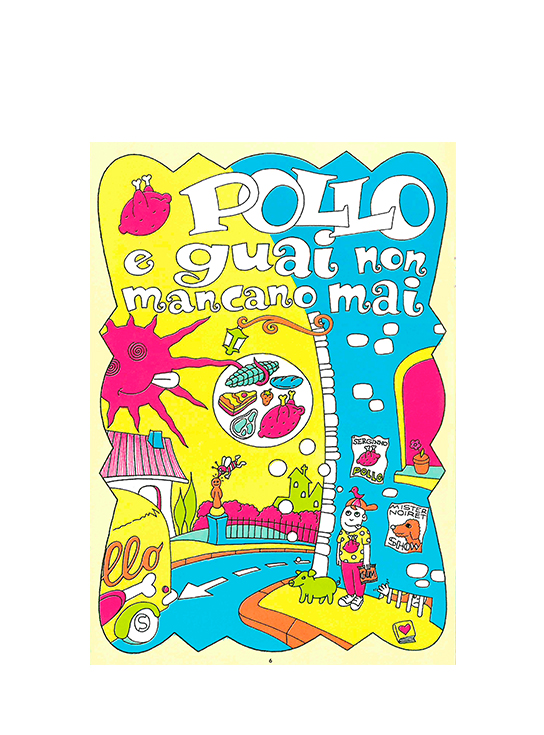

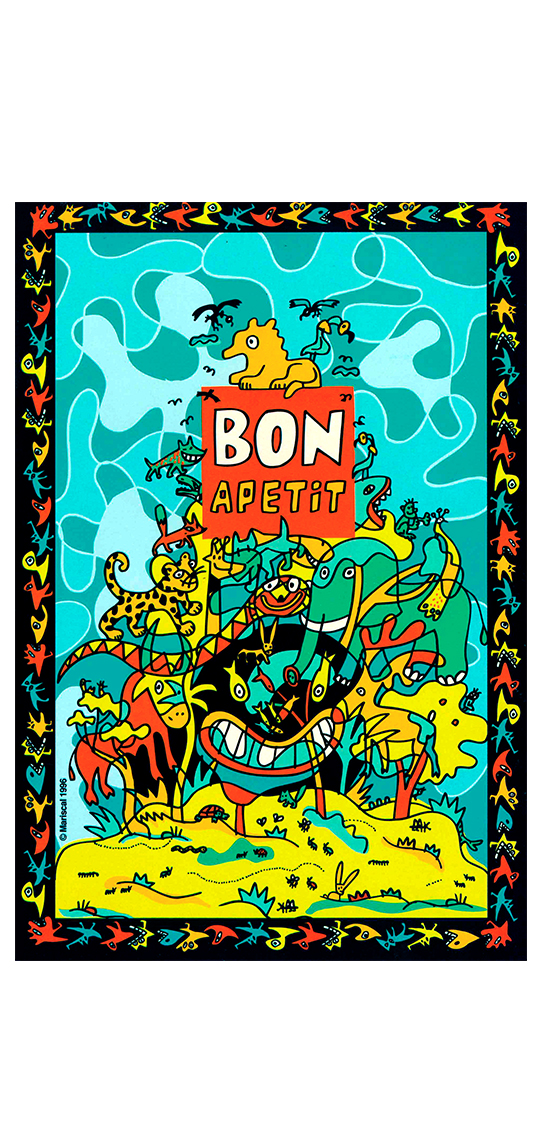

The operation was presented with a small publication that brought together the stories and characters created to enliven the kitchen items selected for the new collection. “A Home Odyssey” by Massimo Giacon, “Chicken and trouble are never missing” by Sergio Cascavilla and “Bon Apetit” by Javier Mariscal.

It was also an ambitious project due to the short circuit created between the way in which this type of objects is usually perceived by the public and the high quality of research, as well as for the materials and production processes chosen to achieve them.

L’oggetto di design nasce da un processo creativo dove convergono saperi e competenze diverse. Ho sempre pensato che non basta la corretta applicazione di criteri funzionali, estetici, produttivi e commerciali: l’oggetto deve nascere nel modo più naturale possibile dal contatto di culture, saperi, tecniche e ispirazioni estetiche differenti. L’ispirazione può venire dal fumetto come dalla biologia, il mio lavoro consiste nel far interagire forze diverse, miscelare conoscenze differenti, individuare nuovi spunti creativi e la loro possibile applicazione.

Con “Comix in the Kitchen” il linguaggio del fumetto fece irruzione nel mondo degli oggetti da cucina. Tre gli autori coinvolti in questo nuovo gioco progettuale: Massimo Giacon, Sergio Cascavilla e Javier Mariscal. L’idea nasceva dal desiderio di affrontare una “no design zone”. I grembiuli, gli strofinacci, i guanti da forno sono generalmente disposti ben visibili nelle nostre cucine, divenendo in tal modo elementi dell’arredo, parti di quel particolare paesaggio domestico, eppure fino ad allora nessuno si era dedicato alla loro progettazione attraverso una vera ricerca formale.

Grazie a Giacon, Cascavilla e Mariscal questi oggetti – insieme a vassoi, tovagliette e tovaglioli – divennero superfici da animare, occasioni per la creazione di uno scenario o una microstoria. Si trattò di inventare personaggi e narrazioni, terreno sul quale i tre autori ritrovarono un contesto famigliare sebbene si stessero confrontando con il progetto di una collezione di oggetti, un lavoro diverso da quello della creazione di un fumetto.

L’operazione fu presentata con una piccola pubblicazione che raccolse le storie e i personaggi ideati per animare gli oggetti da cucina selezionati in quella inedita collezione. “A Home Odissey” di Massimo Giacon, “Pollo e guai non mancano mai” di Sergio Cascavilla e “Bon Apetit” di Javier Mariscal.

Fu un progetto ambizioso anche per il cortocircuito che creò tra il modo in cui questo tipo di oggetti è solitamente percepito dal pubblico e l’alta qualità della ricerca, nonché dei materiali e dei processi produttivi scelti per realizzarli.

Story

Interview with Paolo Fabbri

17/03/2016

In 1996 I met up with the semiologist Paolo Fabbri in Paris, having known him professionally for several years. We discussed and reflected on our work during a long chat in his sitting room. Even today, after many years, I still find his observations really interesting and stimulating.

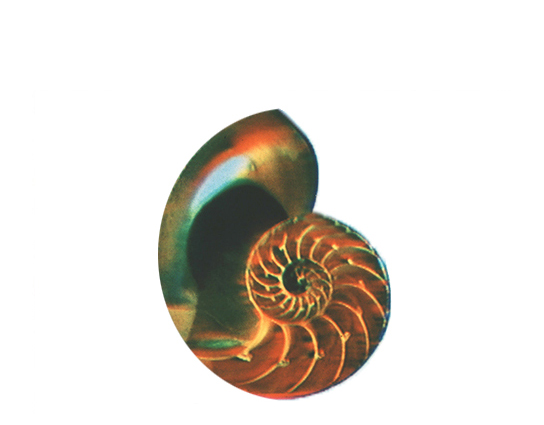

The object as a go-between and the object of meaning

“[...] in our reflections on objects, we have now reached the point where we need to distinguish between the productive aspects of the object – i.e., its being an articulated product thanks to, and with, an attributed meaning – and the object as a go-between, that is to say the object as a connection either between an individual and himself or between several individuals. When we say that an object acts as a go-between for an individual and himself, we mean that it is possible to be both the giver and the receiver of the object at the same time.”

The division of the object

“In the first case, namely that of different parts, we should stress the importance of two further aspects that add to the problems of form (which have always be developed by designers using a rationalist and above all ‘actionalist’ model). The first of these two aspects concerns the internal shape of the objects, i.e. their ability to be broken down into separate parts; in other words, this is the relationship between the object as a whole and its separate parts. This we call the ‘division of the object’. Let us take the Brionvega radio as an example here: its success was due precisely to the fact that it was divided into several parts. Objects could, therefore, be called diptychs, triptychs, quadriptychs, etc., that is to say, ‘articulated things’.

The other aspect to be taken into account concerns substances. Objects are made in the world and form part of the world, even if created using artificial, non natural substances”.

Anthropomorphisation and biomorphisation of the object

“The elemental context is crucial here, that is, the context within which the objects have a role to play and the elements used to create these. This issue has been given a lot of thought, especially when it comes to separating the natural from the artificial. We are surrounded, on the one hand, by objects that are not only fed up with being artificial, but which we would also like to see pervaded with an active power; objects that are not really anthropomorphic, but biomorphic, almost alive. On the other, however, we are filling our homes with artificial Nature (witness the passion for bonsai trees).

Just as there are household electrical appliances, so there are now ‘natural’ appliances. It would therefore be interesting to discover all those objects in-between, from the ‘alive’ to the ‘non-alive’. Science is now studying natural units, such as viruses, that make us wonder if they can really be classed as being ‘alive’. What are the criteria for such a classification? It is most curious, this new obsession of ours. In an age of increasing artificialisation, we are reacting by trying to make objects alive, active, a fetish. On the other hand, there is the process of making natural objects artificial: the object/plant is, somehow, the same as the plant/object.”

Aesthetic understanding

“It is very interesting here to take into consideration both the aspects of how an object is used in the world’s elements and how we feel about the substances making up the objects.

There is a pertinent paradoxical episode here. Some years ago, in France, there was a move against those little toy-like vaguely anthropomorphic objects made from a material with a viscous texture… There was a wave of indignation: ‘Get rid of these horrible things.’ The objects in question were slightly gooey little monsters, at the time when “Gremlins” was on general release at the cinema… Now the example of gooeyness is very interesting. Gooeyness is horrible. The Alien is gooey: that is why we do not like it, not because it eats people; tigers, too, eat people, but they are soft, smooth, beautiful, photogenic, while the Alien is ugly, gooey and gloopy.

The question of our rapport with substances in the world, and our various ways of seeing them, needs looking into. The question of the consistency, the texture of an object is of great importance. Much is made of an object’s smoothness, likewise dryness, but perhaps we should now experiment by looking in another direction, i.e. a taste for the distasteful.

What is this taste for the distasteful? It is the question of ‘aesthetic contact’ vs. ‘non aesthetic contact’. Aesthesia is the relationship between substance and perception.”

Thesis - Antithesis - Prothesis

“Let us also consider the artificialisation of the human body and the naturalisation of objects: the reification of subjectivity. In other words, this is,, as MacLuan has always called it, the problem of the prothesis. People are becoming ever stronger thanks to the use of protheses: the cane that extends the hand; the stick used by the blind to touch things… it is the tip of the stick that actually touches things, allowing the blind to ‘feel’; the stick therefore becomes part of his body. Some time ago I jokingly said that we were no longer in the age of thesis - antithesis - synthesis, but that of thesis - antithesis - prothesis. So we have body - man - object (thesis, antithesis and prothesis): artificial man. However, we are forgetting the phenomenon of the reification of the subject, which is the exact opposite of the phenomenon of the anthropomorphisation of the object. We need to look at it in both ways: there is a kind of subjective pathos in the idea that we are losing our whole subjectively, if such a thing has ever existed.”

Nel 1996 andai a trovare a Parigi il semiologo Paolo Fabbri, con il quale da alcuni anni avevo iniziato a dialogare. In una lunga chiacchierata nel suo salottino emersero molti spunti di riflessione sul lavoro che stavamo conducendo. A distanza di anni, trovo ancora estremamente interessanti e stimolanti le osservazioni fatte allora.

L’oggetto come tramite e l’oggetto di senso

“Nella riflessione sugli oggetti si è arrivati al tentativo di una distinzione tra l’aspetto produttivo dell’oggetto – ossia come prodotto articolato da un senso e con un senso attribuito – e l’oggetto tramite, cioè l’oggetto che funziona come tramite tra gli individui, sia dell’individuo con se stesso, sia tra più individui. L’oggetto come tramite verso se stessi, in cui è possibile essere nello stesso tempo il destinante dell’oggetto e il suo destinatario.”

La partitura dell’oggetto

“Nel primo caso, nel caso dell’articolazione, sarebbe importante sottolineare l’importanza di due aspetti che si aggiungono alle problematiche della forma (quelle da sempre sviluppate dai designer, sul modello razionalista e soprattutto azionalista). Il primo aspetto riguarda la forma interna degli oggetti, la loro articolazione in parti, ossia la relazione che c’è tra la totalità dell’oggetto e le sue ripartizioni. In una parola: la ‘ partitura dell’oggetto’. Per esempio la radio Brionvega: il suo successo si deve proprio al fatto che era articolata in più parti. Si potrebbe così pensare di ridefinirli dittici, trittici, quadrittici, cioè ‘cose articolate’.

L’altro aspetto da considerare riguarda le sostanze. Gli oggetti sono fatti nel mondo, sono sue parti, anche se creati con sostanze artificiali e non naturali”.

Antropomorfizzazione e biomorfizzazione dell’oggetto

“Occorrerebbe così mettere in luce i contesti elementari, cioè gli elementi dentro cui giocano gli oggetti e quelli di cui sono fatti gli oggetti. Anche su questo si è molto riflettuto, specie per opporre il naturale e l’artificiale. Da una lato siamo circondati da oggetti che, non solo sono stufi di essere artificiali, ma che vorremmo anche più carichi di un potere attivo. Oggetti non propriamente antropomorfizzati, ma biomorfizzati, quasi vivi. Dall’altro lato, invece, è sempre più diffusa la presenza nelle nostre case di nature artificializzate, basta pensare alla passione per i bonsai.

Come c’è l’elettrodomesticato, adesso c’è il natura-domesticato. Quindi sarebbe interessante trovare tutti quegli oggetti intermedi che vanno dal vivente verso il non-vivente. La scienza sta studiando delle unità naturali, i virus ad esempio, di cui ci si domanda se siano veramente viventi. Qual è il criterio di attribuzione della vita? E questo è abbastanza curioso. E noi abbiamo una ossessione. In un’epoca di crescente artificializzazione si reagisce tentando di rendere attivo, feticcio, l’oggetto. Dall’altra parte, invece, ci sono dei processi di artificializzazione della natura: l’oggetto-pianta è in qualche misura la pianta-oggetto”.

La conoscenza estesica

“In questa prospettiva diventa molto interessante prendere in considerazione sia gli aspetti dell’uso dell’oggetto negli elementi del mondo, sia il tipo di relazione della sensibilità rispetto alle sostanze con cui sono fatti gli oggetti.

C’è un episodio paradossale che può essere ricordato a questo proposito. Anni fa in Francia ci fu una polemica contro dei semi-giocattoli, vagamente antropomorfi, fatti con un materiale che aveva una consistenza vischiosa… ci fu un’ondata di indignazione: ‘Togliete quelle orribili cose.’ Erano dei bei mostriciattoli un po’ vischiosi, era l’epoca in cui andavano di moda i Gremlins al cinema eccetera. Ora, l’esempio del vischioso è interessantissimo. Il vischioso è orribile. Alien è vischioso: è per questo che ci dà fastidio, non perché mangia la gente; anche le tigri mangiano la gente, ma sono morbide, lisce, belle, fotogeniche…, mentre Alien è brutto, vischioso e cola.

Su questo problema della relazione delle sostanze del mondo e di certi tipi di modalità della percezione dovremmo interrogarci. Il problema della consistenza degli oggetti è di grande importanza. Noi abbiamo molto giocato sul liscio, come sul secco, ma può darsi benissimo che si debba sperimentare nella direzione di un’altra forma del sensibile, cioè un gusto del disgusto.

Che cos’è il gusto per il disgusto? È la questione del contatto estesico, non estetico: l’estesia è la relazione tra la sostanza e la percezione.”

Tesi - antitesi - protesi

“Un’altra questione riguarda l’artificializzazione del corpo umano e la naturalizzazione degli oggetti: la reificazione della soggettività, come ha detto sempre anche MacLuan, il problema delle protesi. Cioè gli uomini diventano sempre più forti attraverso la protesi: il bastone che allunga la mano, quello del cieco che tocca le cose… è la punta del bastone che tocca e la sensibilità della persona non vedente è lì, quindi il bastone fa parte del suo corpo. Tempo fa ho detto scherzando che non eravamo più nell’epoca della tesi - antitesi - sintesi, ma della tesi - antitesi - protesi. Quindi: corpo - uomo - oggetto, tesi, antitesi e protesi: l’uomo artificiale. Ci stiamo però dimenticando del fenomeno di reificazione del soggetto. Il fenomeno contrario a quello dell’antropomorfizzazione degli oggetti: bisognerebbe guardare in tutti e due i sensi. C’è una specie di pathos soggettivistico in questa idea che stiamo perdendo la nostra intera soggettività, come se ce ne fosse mai stata una”.

Story

The Catalogue Comix in the Kitchen 1996

Story

Alessandro Mendini’s Small Reflections

10/03/2016

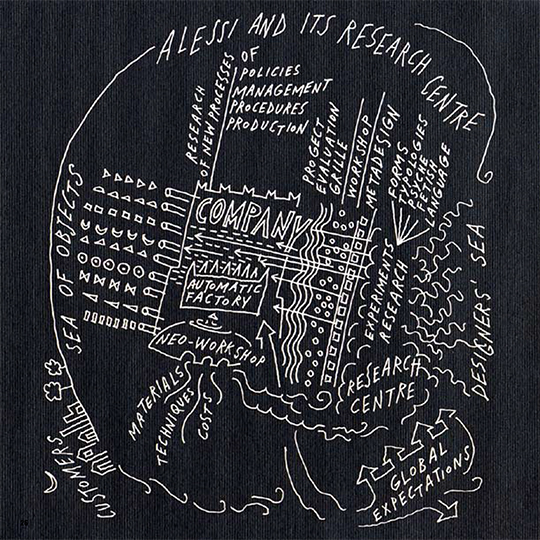

“When a company takes a critical look at itself, when it conducts a process of self-analysis, something intelligent and unexpected will always come of it. There are many ways to conceive of a Study Centre, and experiences of this kind can be found throughout the history of design, a little bit everywhere, although they are a rare phenomenon, something special. Alessi’s Study Centre was one of these.”

“Every industry, every craftsman, every architect and designer should have their own research centre. These places of experimentation create the conditions for the finest encounters, synergies that could not otherwise be realised.”

“Today many industries are fertile, several are declining, some production methods are changing radically. There is hope (but also the rhetoric) of self-production, the schools are on standby, times are beautiful, tough, violent and very difficult.”

Alessandro Mendini

“Quando un’azienda volge uno sguardo critico verso se stessa, quando compie un’attività di auto-analisi, nasce sempre qualcosa di intelligente e inaspettato. Sono molti i modi di concepire un Centro Studi ed esperienze di questo genere si trovano lungo tutta la storia del design, un po’ dovunque, anche se sono fenomeni rari, speciali.

Il Centro Studi Alessi è stato uno di questi.”

“Ogni industria, ogni artigiano e ogni progettista dovrebbe avere il suo centro di ricerca. Questi luoghi di sperimentazione creano le condizioni per incontri di eccellenza, sinergie che altrimenti non avrebbero modo di realizzarsi.”

“Oggi molte industrie sono fertili, diverse sono in declino, alcuni metodi di produzione stanno cambiando radicalmente, c’è la speranza (ma anche la retorica) della autoproduzione, le scuole sono in stand-by, l’epoca è bella, dura, violenta e difficilissima”

Alessandro Mendini

Story

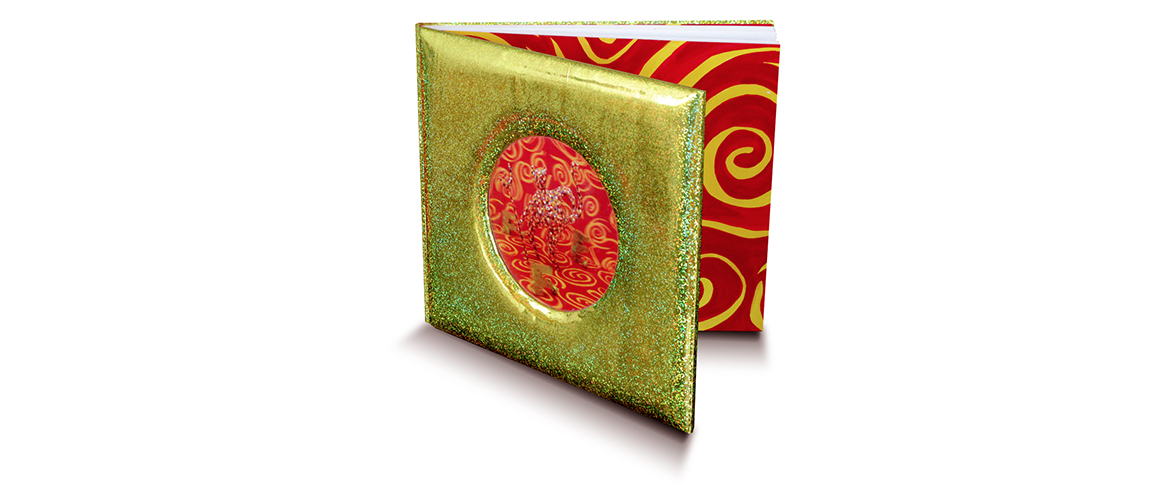

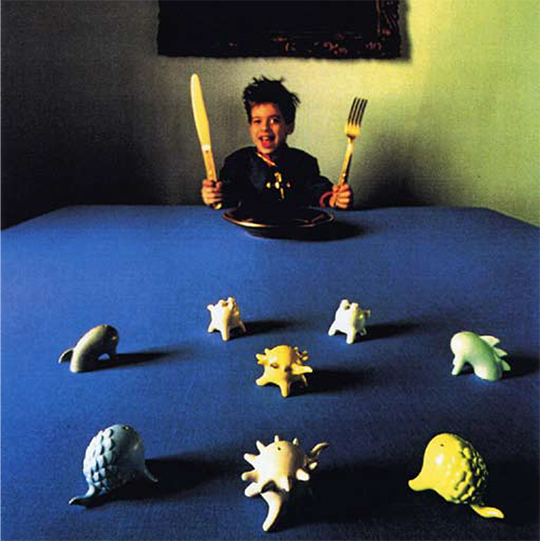

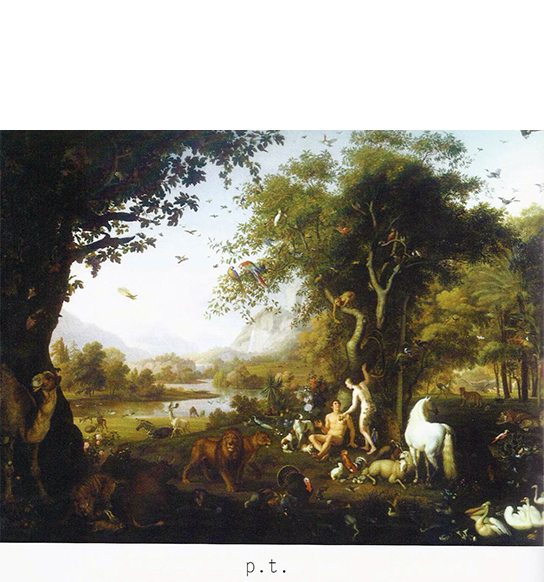

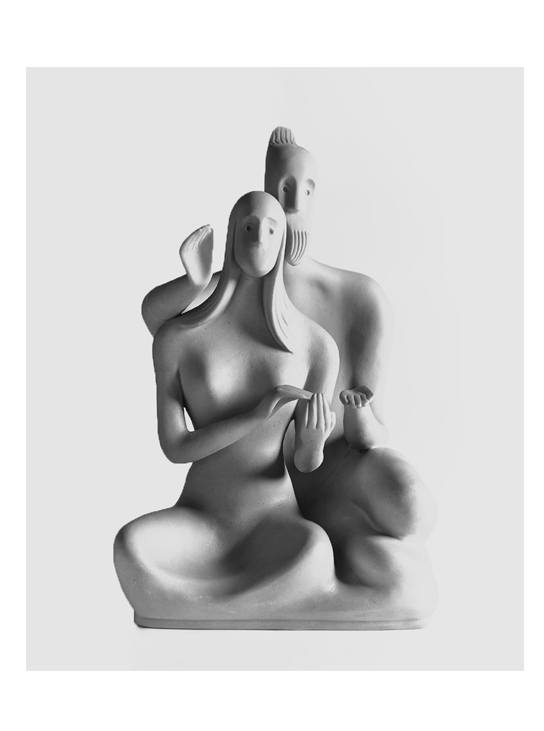

F.F.F. (Family Follows fiction) FORTEMENTE FACEVAMO FUOCO

05/03/2016

Yes, we were on fire! Ablaze! No one got burnt, though, because we were all made of its very same nature, the fire and us: we blended together and cross-pollinated each other and thanks to the fire itself did so without any pain (or just a little pain) and without any burns (or maybe just a few).

Purity of intent, springtime vitality of participation, sincerity of words and gestures, a kind of “adult childhood” came over us!

During these meetings of the laboratory/workshops, amongst ourselves, before the objects we thought about meta-objects, before the project we thought about meta-projects, before thinking we meta-thought, before speaking we meta-spoke, before designing we meta-designed, in practice before ‘taking action’ we took as long as needed to become the people who would have to take action. It was fantastic!

We thought—and we said so among ourselves—that a design that only thinks about the objects and not also about itself and its future, neglecting itself, is not design, if only because it has no self-respect.

We read and listened to the psychoanalyst (Fornari) who came to talk about putting affections in order, analyzing and codifying them.

We read and listened to the sociologist (Franco) who guided us through the cities and countrysides of the world making us notice every detail of the future of our fellow men.

We read and listened to the company men (Alberto, Danilo, Massimo) who candidly told us the truth about their home/company and about what they were looking for, maybe not telling the whole truth, but a big part of it, yes .

The man of the home/company wasn’t lying just to seduce us, there was no need for that because all of us were already on fire, he wasn’t lying to himself either because the reality of his home/company was pleasant and therefore needed no analgesic lies in order to forge ahead and, consequently, neither did we ‘designers’ feel the need to put on aires.

We ‘designers’, some of us semi-beginners and others already somewhat ‘initiated’ but still ‘in the rough’, would read and listen over and over again, very seriously and with respect and affection, to all who passed through bearing facts, concepts and questions, we reflected in solitude or in small groups on the things we’d read and heard and then we’d came back to them with questions, some sort of babbling response, some beginnings of perceptions, some signs, some dreams, some drawings.

And gradually, as one meeting followed another, we began to become more than we were at the beginning, both we, the ‘designers’ and they, the ‘bearers of questions’.

The ferryman/woman? of this little journey we’d embarked upon together was Laura; she brought us together, prodded us, urged us, gave us food and drink, unnerved us, smiled at and accompanied us.

She, too, gradually became something else during this journey, and the beauty is that no one, neither Laura nor the man of the home/company, nor the psychoanalyst, nor the sociologist, nor we ‘designers’ knew where we were going and what risks we might encounter, but we went along out of appetite, engulfed in the gravitational waves, it was natural… destiny.

Then after having traveled awhile with the meta-things, the ‘things’ began to arrive, the ideals became objectified, unreality was realized, metaphysics appeared to us in its physical form, after all, De Chirico called metaphysics half physical and half not!

At some point in the little journey the home/company became a workshop that made actual things, thanks to its thoughty technicians and its handy technicians magical and delicate models and prototypes emerged: the first visible epiphenomena of meta-things that we’d conjured up during our little journey, stammering appearances, loving, full of good hope and good health.

Laura, Alberto, Danilo, Massimo and we ‘designers’, guided and advised by the bearers of questions (Gozzi, Cecla…) who followed us, standing by our collective side also in this phase of ‘objectual apparition’, we all experienced vivid emotions as we began to see the birth of the possible, and hoped that these babblings of form and material that were appearing would grow up strong and healthy and go on to have an autonomous life in the outside world.

When Laura, Alberto & Co. and a little bit we ‘designers’ as well considered that the objectification of the ideal was in its final stage and ready to be shown in the shops, the next step was to present this objectification to the ‘market captains’ who worked in or for the home/company, and they, watching and touching with care and kindness these objects/infants, accompanied them to their adult life understanding their value and knowing how to place them on the various shelves of the various marketplaces scattered about, knowing how to criticize or encourage them and in any case knowing how to treat them to get them to talk to the people.

In the phase just before diving into the market pool, the alchemist Giacomo transformed these objectifications of ideals into images by working with light and shadow, in a certain sense taking a final step backwards: from matter and a freshly-minted physical presence, we returned to the evocative power of an image inserted into a conceptual landscape that by then had become clear to everyone, here at the end of the journey we’d started together.

Giacomo’s images, along with texts by Laura, Alberto and others, were turned into a book/catalog called FFF with a glistening cover and contents like the special effects lightshow of a pop/folk festival.

When the people with whom we wanted to speak saw on the shop’s shelves this illuminating book and these objects/fires they adopted the FFF family and welcomed it into their homes, touching and using the objects in their daily lives.

These objects, generated by a common journey, penetrated into the populace’s space and time with fluidity and relevance, some more than others but all of them have since generated landscapes and families (landscapes at times legitimate and harmonious, other times also plagiarized and awkward coming from other places, but that’s the way it went!) and, above all, they communicated sincerity and enthusiasm to those who adopted them.

These laboratory/workshops did not have the objective of simply ‘filling up holes’, real or presumed, that some market researcher had, with more or less foresight, identified in the marketplace, rather the objective was to step back and seriously reflection and analysis before proposing things to the people of the world, stepping back and then taking a running start like athletes do before the starting pistol in order to move more powerfully and with more relevance.

Today, are these laboratory/workshops still conducted, in these safe-houses that allow the time needed to acquire the resources required for designing? I don’t know! Maybe yes, maybe no.

Personally I starting doing and thinking about other things and it’s been some time now that I haven’t kept up with what’s going on.

It would be nice, however, and helpful if Laura and her co-ferrymen created another big ol’ laboratory/workshop today to bring together those who today have the strength, the desire and the pleasure to once again study together, to reinvent fantastic, never-before-seen landscapes to send off around the world, proposing them to people everywhere; landscapes that are worthy of us and our future.

Pierangelo Caramia

Sì, era fuoco! Proprio fuoco! Ma non ci si scottava perché eravamo fatti della stessa natura, il fuoco e noi: ci si amalgamava e ci s’impollinava con esso e grazie a esso senza dolore (o con poco dolore) e senza (o con poche) scottature.

Purezza degli intenti, vitalità primaverile del coinvolgimento, sincerità delle parole e dei gesti, una specie di « infanzia da adulti » ci abitava!

Durante questi incontri nella bottega laboratorio tra noi prima che agli oggetti si pensava ai metaoggetti, prima che al progetto si pensava al metaprogetto, prima di pensare si metapensava, prima di dire si metadiceva, prima di disegnare si metadisegnava, in pratica prima di « agire » si prendeva il tempo che ci vuole per diventare chi dovrà agire, insomma!

Noi pensavamo - e ci dicevamo tra noi - che un design che pensa solo agli oggetti e non anche a se stesso e al suo divenire trascurandosi non è design, se non altro perché non ha amor proprio.

Si leggeva e si ascoltava lo psicanalista (Fornari) che veniva a parlarci del suo mettere ordine nell’affetto analizzandolo e codificandolo.

Si leggeva e si ascoltava il sociologo (Franco) che ci portava in giro nelle città e nelle campagne del mondo facendoci notare tutti i dettagli del divenire dei nostri simili.

Si leggeva e si ascoltava l’uomo dell’impresa (Alberto, Danilo, Massimo) che candidamente ci diceva la verità sulla sua casa/impresa e su cosa cercassero, magari non ce la diceva tutta la verità, ma una gran parte di essa sì.

L’uomo della casa/impresa non ci mentiva al fine di sedurci, non ce n’era il bisogno perché eravamo già lì infuocati insieme, non mentiva neanche a se stesso del resto perché la realtà della sua casa/impresa era piacevole e non aveva bisogno quindi di menzogne analgesiche da ingerire per procedere e, di conseguenza, anche noi « designers » non conoscevamo imposture.

Noi « designers », alcuni semi-principianti e altri già principiati ma ancora non finiti, leggevamo e ascoltavamo a più riprese con serietà, rispetto e affetto tutti questi portatori di fatti, di concetti e di domande, riflettevamo in solitudine o a piccoli gruppi sulle cose lette e sentite e poi tornavamo da loro con domande, qualche balbettio di risposta, degli inizi di percetti, dei segni, dei sogni, dei disegni .

E a poco a poco nel susseguirsi degli incontri si cominciava a diventare altri rispetto a quelli che eravamo all’inizio, sia noi « designers » sia loro « portatori di domande ».

Il traghettatore/trice ? di questo viaggetto che si faceva insieme, era Laura che ci riuniva, ci pizzicava, ci incitava, ci dava da bere e mangiare, ci innervosiva, ci sorrideva e ci accompagnava.

Anche lei diventava altro a poco a poco viaggiando e il bello è che nessuno, né Laura, né l’uomo della casa/impresa, né lo psicanalista, né il sociologo, né noi « designers » sapevamo dove stavamo andando e con quali rischi, ma si andava per appetito e per onde gravitazionali nelle quali ci trovavamo, per naturalità e destino.

Poi dopo aver viaggiato sulle e con le metacose cominciavano ad arrivare le « cose », gli ideali si cosificavano, l’irrealtà si realizzava, la metafisica ci appariva nella sua forma fisica, del resto De Chirico definì la metafisica metà fisica e metà no!

La casa/impresa diventava a un certo punto del viaggetto un’officina che realizzava, grazie ai suoi tecnici di testa e ai suoi tecnici di mano, magici e delicati modelli e prototipi: primi epifenomeni visibili delle metacose pensate durante il viaggetto, apparizioni balbettanti, amorevoli e di buone speranze e buona salute.

Laura, Alberto, Danilo, Massimo e noi « designers » guidati e consigliati dai portatori di domande (Gozzi, La Cecla…), che ci seguivano attorniandoci anche in questa fase di « apparizione oggettuale », vivevamo delle forti emozioni cominciando a veder nascere il possibile e desiderando, per questi balbettii di forma e materia che apparivano, una sana crescita e una vita successiva autonoma nel mondo.

Quando Laura, Alberto & Co. , e un po’ noi « designers » anche, consideravamo che la cosificazione dell’ideale fosse nella fase finale e pronta per mostrarsi sui banchi del mercato si faceva vedere questa cosificazione ai “capitani dei mercati” che lavoravano nella o per la casa/impresa e loro, guardando e toccando con attenzione e amorevolezza questi oggetti/infanti, li accompagnavano verso la loro vita adulta sapendoli valorizzare e inserire nei vari banchi dei vari mercati, sapendoli criticare o incoraggiare e sapendo in ogni caso come trattarli per farli parlare alla gente.

In questa fase di pre-tuffo dal trampolino nella piscina del mercato Giacomo l’alchimista trasformava queste cosificazioni degli ideali in immagini lavorando con le luci e le ombre, facendo in qualche modo un’ultima retromarcia: dalla materia e presenza fisica appena apparsa si tornava alla forza evocativa di un’immagine inserita in un paesaggio concettuale che era diventato ben chiaro a tutti ormai alla fine del viaggetto fatto dall’inizio insieme.

Le immagini di Giacomo accompagnate dai testi di Laura, Alberto e altri si misero in un libro/catalogo chiamato FFF con la copertina che brillava e che conteneva effetti speciali come una luminaria di festa pop/popolare.

Quando le persone alle quali volevamo parlare hanno visto sui banchi del mercato questo libro luminaria e questi oggetti/fuochi hanno adottato questa famiglia FFF e l’hanno fatta entrare nelle loro case, toccando e usando gli oggetti nelle loro vite quotidiane.

Questi oggetti generati dal viaggetto comune sono penetrati nello spazio e nel tempo delle persone con fluidità e pertinenza, alcuni di più altri di meno, ma tutti hanno generato poi dei paesaggi e delle famiglie (paesaggi legittimi e armoniosi a volte e paesaggi scopiazzati e sgraziati che arrivavano da altri luoghi anche - ma cosi è andata !) e, soprattutto, hanno comunicato a chi li ha adottati sincerità ed entusiasmo.

Questi laboratori/bottega non avevano l’obiettivo di – semplicemente - « riempire buchi », veri o presunti, del mercato che erano stati segnalati da vedette del mercato, con vista più o meno lunga, ma l’obiettivo di fare un passo indietro di riflessione e analisi serie prima di proporre cose alle persone del mondo, passo indietro per prendere la rincorsa come fanno gli atleti prima dello scatto per potersi muovere con più potenza e pertinenza al momento opportuno.

Oggi si fanno ancora questi laboratori/bottega in cui si prende il tempo che ci vuole per acquisire le risorse per progettare? Non lo so! Forse sì, forse no.

Personalmente mi sono messo a fare e a pensare altre cose da qualche tempo e non sono molto informato a riguardo.

Sarebbe bello e utile però, secondo me, che Laura con i suoi co-traghettatori creasse un laboratorione/bottegona oggi che raccogliesse chi ha oggi la forza, il desiderio e il piacere di studiare insieme di nuovo per inventare ricchi e esatti paesaggi fantastici mai visti prima da portare in giro e proporre alla gente del mondo e che siano degni di noi e del nostro futuro.

Pierangelo Caramia

Object

Story

Pummaroriella 2006

Story

The Encounter

19/02/2016

“You will be more abandoned once

Things have abandoned you.

Things don’t make demands;

They say yes to everything.

Things would make

Fantastic lovers.

(Jiri Orten)

It’s still about objects and people; but this time, perhaps, a bit more about people.

But let’s approach this is an orderly fashion, because, after all, this is narration, and the time sequence is important. To cut a long story short, what happens is that, after several years, a group of individuals linked by their shared interest in the conception and production of objects, decide to take a break.

How to go about reflecting on what’s already been done? How to see its effects on the present? How to put experience to use, in order to see what’s going on?

Casting a backward glance, the informal association shaped over years of interaction between the workshop, the craftsman’s outlook, and inventors of objects and architectural settings decides that the time has come to create a space meant specifically for experimentation. The Centro Studi Alessi is born.

Alberto Alessi and Alessandro Mendini share the same dream. They meet and involve another person who, during her training, had already pointed out a similar: Laura Polinoro.

Put like this, it all sounds simple. But an outside observer (such as myself)

notices right away that this is no normal development. In order for Alessi workshop to create a Study Center, various unorthodox elements had to be present.

It strikes me that Alessi’s way of going about things has been unusual in the context of the production of objects on an industrial scale in Italy (and elsewhere).

Because, in this case, things didn’t happen just on the basis of ‘corporate experience’, or just as the consequence of some debate about culture. There are unmistakable signs left by a complex of personal relationship and of the flexibility of a history made up of informal conversations and shared meditations on what was being done.

This workshop atmosphere, which Alessi has by some miracle managed to preserve up to now (but will we succeed in convincing them to keep on in the same manner?) is closely connected with a freely flowing human dialogue: objects are important, of course, but as a link between people. And the Centro Studi, born of a backward glance, is anything but a tight-laced laboratory where industrial prototypes are created. It is, rather, an amplifier for doubts and ideas, where the elements of ‘let’s give it a try’ and ‘it’s important to make mistakes’ mean that there’s always as good amount of fresh air in circulation.

In short, I think that, if the Centro Studi Alessi has become a place for experimentation, this is owing above all to the fact that it has only an indirect ‘relevance’ to a strictly corporate way of going about things.

Its ‘fuzzy logic’ and elasticity of mindset are, most certainly, those of the craft workshop, with its characteristic time frames. What’s at stake here is the creation and maintenance of a structure of relationship able to put to fruitful use every apparent deviation from the norm, everything which is ‘off the subject’. Alberto Alessi has explained […] this characteristic of the shop, where the precision with which each single phase is carried out is matched by a lack of precision regarding the time frame. It is time, stretching out or drawing itself in, that gives greater or lesser substance to an object. The moment at which the latter is ‘made’ is just one moment among the many in its life.

Another basic tenet of the traditional craftsman’s shop which has carried over into the Centro Studi is that ‘the windows must be left open so that the outset world can stick its head in, not infrequently upsetting preconceived plans and schedules’.

This has been Laura Polinoro’s task since the very beginning: to embrace the confusion caused by new ideas, to play around with elements in a way that might appear irreverent to many connected with Alessi’s past.

This is the pragmatic, discussion-oriented method of workshop and construction sites. We might take shipyards as an example, or master craftsmen […]. The flow of people who drop by ‘just to watch’ is unending.

The master makes his measurements and cuts the wood, but there’s always someone there talking at him, ready to express an opinion, […] seagoing people, who are already able to perceive, in the skeleton of the boat as it takes shape, its ability to stand up to wind and waves. But without those open doors, without this interactive process of defining of the work in progress, the master boatbuilder wouldn’t exist. The very garbo or garboard he uses to shape the curves of the boat is a tool for dealing in relationships. It reflects a way of doing things based on an idea of harmony between the parts, […] changing along with the outside world […]. I imagine (and, to certain extent, I know, having come in contact with it both on and off its own premises) that the Centro Studi Alessi came into being as something resembling my master shipbuilder’s yard; as a place, that is, where today’s objects and their power over us might find room to express themselves. In this sense, Alessi, through the Centro Studi, aims to understand a little better ‘what’s happening out there in the world,’ before making any attempt to intervene in that world.

This gives rise to what Mendini has called a post-functional anthropological vision of object-making. […] The objects people use become companions, taking on symbolic power that helps us go on living […] a given object is at once merchandise, an object of affection, a tool for use and exchange, a fetish, a souvenir, and all those other identities one may imagine for it. […]

The transformation of the world of objects has made its forceful entry into the Centro Sudi. How? I think the most interesting answer is that it came in because there was room for it. It’s a space for exploration not aimed directly at a production-oriented end result, once more a space dedicated to studying topics such as, for instance, ‘fetishism in traditional and primitive societies.’ […]

The Centro Studi has worked using a patient, open methodology, gathering together the ideas of outside researchers, anthropologists, historians, semiologists and ethnopsychiatrists, along with those of inventors, designers, artists, and architects. What’s worked out has been the way the operation itself was set up. Ideas really have flowed and circulated. I mean that even the most remote suggestions have been taken up and batted around at various levels.

The idea that objects have therapeutic influence, […] or that a certain everyday animism transforms objects for practical use into animated toys.

All this has become drawings and prototypes and, every now and then; a series of mass-produced objects.

[…] I say this in the full awareness that the objects themselves will in turn influence what people ‘out there’ are doing.

And this is the other important element: the taking of objects – ‘things’- seriously, saving them from the banalizing impact of functionalism, from a reduction to their mere economic value. […]

Alessi’s public has accepted, surprisingly easily, the changes in tone, the drastic breaks, the U-turns of these past years; all these are made acceptable as the development of a discourse by the fact that the objects created refer back to an original collector.

It’s like the case of Utz, a character in a novel by Bruce Chatwin who collects porcelain: his motivations make for an intriguing story, which leaves room for interpretation and which masks a (subtle or intense) irony. Is he a collector? A spy? A happy or a desperate man? Or one who has always hung onto his sense of irony, so that his collecting reflects the world’s ambiguous richness? […]

And it is amusing to note that the metaphor of the window used above, in order to express the way the Centro Studi ‘reflects’ on the destiny (and reflects the destiny) of objects out there, on the manner in which we today get objects to keep us company, in turn sends us back to real shop windows, those where Alessi objects are on display. In the display window, too, Alessi objects make up a context […]. In this sense, objects ‘animate’ one another and create stories (and stand up on their paws) […].

But something has changed in recent years: to functionalism, and then to the functionalism of collectable beauty, there has been added a return to the emotional value of objects, and thence to their use as go-betweens in relationship. Yes, these are collections; but collections referring to the relationships people can set up between objects. Attentive to what the world out there is beginning to feel, the Centro Studi has been developing an interest in the fact that […] objects are go-betweens in relationship, alliances, fights, misunderstanding, loves and hates. A new period of research is getting under way; and the contextuality for which collections were once metaphor is now a contextuality of interpersonal relationships.

Objects pass from hand to hand, rest between bodies, touch and are touched by men and women, misdirecting or facilitating contact between them, becoming the present or a memory, a gift or a restitution, saying ‘I’m giving you this to show you what I’m like’[…].

Franco La Cecla, 1996

“Sarai più abbandonato

quando le cose ti

abbandoneranno.

Le cose non domandano;

Dicono di sì a tutto.

Le cose sarebbero

delle magnifiche amanti.

( Jiri Orten)

Si tratta ancora una volta di oggetti e di persone, ma questa volta forse un po’ più di persone.

Ma andiamo con ordine: perché si tratta comunque di una narrazione e i tempi sono importanti. Insomma accade che alcune persone, unite da un interesse comune alla ideazione e produzione di oggetti, decidano, dopo parecchi anni, di darsi una pausa. Come riflettere sul già fatto? Come vederne gli effetti sul presente? Come fare funzionare l’esperienza per guardarsi intorno?

Una frequentazione che si era formata in anni di relazione tra officina, mentalità artigiana, ideatori di oggetti e di architetture si guarda indietro e decide che è arrivato il momento di dare uno spazio specifico alla sperimentazione. Nasce il Centro Studi Alessi.

Lo concepiscono per accenni reciproci Alberto Alessi e Alessandro Mendini. Incontrano e coinvolgono qualcuno che nei suoi percorsi di formazione aveva accennato a una cosa analoga, Laura Polinoro.

Le cose poste in questo modo sembrano semplici. Ma a uno sguardo esterno (come il mio) salta all’occhio che questo non è uno sviluppo usuale. Perché l’officina Alessi desse vita a un centro studi, c’era bisogno di alcuni germi ‘insoliti’.

Mi pare che la maniera di procedere dell’Alessi sia stata anomala rispetto al panorama italiano (e non) della produzione di oggetti su scala industriale.

Insomma qui le cose non sono nate da una ‘esperienza aziendale’ soltanto o da un dibattito culturale soltanto. Ci sono le tracce forti di un insieme di rapporti personali e di tutta la elasticità di una storia fatta di chiacchiere, riflessioni e chiacchiere su quanto si faceva. Questa aria da bottega che miracolosamente l’Alessi ha fino a ora mantenuto (riusciremo a convincerli a continuare così?) è proprio legata a un fresco dialogo umano, all’importanza degli oggetti sì, ma come tramite tra le persone.

Il centro studi, nato da un volgersi un istante indietro non è il serioso laboratorio di una industria di prototipi. È più che altro una cassa di risonanza di dubbi e di proposte, dove l’elemento del ‘tentiamo’ del “gli errori ci sono essenziali” fa sì che ci sia una buona dose di correnti d’aria.

Mi pare, insomma, che se il Centro Studi Alessi è diventato un luogo di invenzione lo deve soprattutto a questo, alla sua non ‘pertinenza’ diretta con una logica strettamente aziendale.

Questo fuzzy logic, questa elasticità è la stessa certamente della bottega e dei suoi tempi. Quello che è in gioco qui è la creazione e il mantenimento di una struttura di relazioni che consenta un uso fertile di ogni apparente scarto dalla norma e di ogni ‘fuori tema’. Alberto Alessi ha spiegato […] questa caratteristica dell’officina dove alla precisione di ogni fase si sovrappone l’incognita delle sequenze. Sono I tempi che nel loro dilatarsi o restringersi danno corpo o meno a un oggetto. Il momento in cui questo viene ‘fatto’ è solo uno dei tanti della sua vita.

Un altro elemento fondamentale della bottega che si riversa sul centro studi è che ‘le finestre vi debbano essere lasciate aperte perché vi faccia capolino, spesso e scompigliando tempi e carte, il mondo là fuori’. E questo è stato dall’ inizio il ruolo di Laura Polinoro, quello di fare, con la confusione del nuovo, il gioco di ciò che ai troppo interni alla storia Alessi poteva sembrare un tantino dissacrante.

Questo metodo si è poi allargato ad altri esterni e giovani progettisti e non, nel tentativo di creare un ‘ideificio’.

È il metodo dialogico e pragmatico delle botteghe e dei cantieri. Un esempio potrebbe essere quello dei cantieri di barche, dei maestri d’ascia […] Il via vai di quelli che ‘stanno a guardare’ vi è ininterrotto. Il maestro prende le misure e taglia le assi, ma c’è sempre qualcuno che gli dà ‘a parlare’ e spesso dando giudizi […] gente che naviga e che quindi legge nello scheletro della barca già una struttura di resistenza a vento e a onde. Ma senza queste porte aperte, senza questa definizione interattiva dell’ opera il maestro d’ascia non esisterebbe. Il ‘garbo’ stesso, lo strumento di misura che egli usa per modanare le curve della barca è un oggetto di relazione. Il “garbo” rimanda a una maniera di fare ‘concertata’ […] che muta a seconda di come cambia il mondo intorno[…]

Il Centro Studi Alessi è nato, immagino (e un po’ lo so per frequentazione dentro e fuori la porta) in questo stesso modo: un luogo dove il cambiamento di statuto degli oggetti oggi e dell’ influenza che hanno su di noi possa trovare spazio per esprimersi. In questo senso l’Alessi con il centro studi si propone un po’ più di capire ‘come va il mondo degli oggetti là fuori’, prima ancora di intervenirvi.

Nasce quella che Mendini chiama una visione antropologica, postfunzionale del fare gli oggetti. […] Gli oggetti che la gente usa si trasformano in compagnia, assumono una forza simbolica che aiuta a vivere […] in uno stesso oggetto sono presenti merce, oggetto d’affezione, oggetto d’uso e di scambio, feticcio, ricordo, e quante altre identità si possono immaginare. […]

La trasformazione del mondo degli oggetti è entrata con forza nel centro studi. E come? Credo che la risposta più interessante è che è entrata perché c’era spazio. Lo spazio di ricerche che non erano direttamente finalizzate alla produzione, lo spazio, ad esempio di una ricerca sul ‘feticismo nelle società tradizionali e primitive’. […]

Il centro studi ha operato con un metodo aperto e paziente, raccogliendo idee di ricercatori esterni, antropologi, storici, semiotici, etnopsichiatri e ideatori, designers, artisti, architetti. Ed è la sedimentazione di queste operazioni che ha ben funzionato. Le idee hanno effettivamente circolato. Voglio dire che anche le suggestioni più distanti sono rimbalzate tra vari livelli.

L’idea che gli oggetti abbiano una influenza terapeutica, […] o che un certo animismo quotidiano trasformi gli oggetti d’ uso in giocattoli animati, tutto questo è divenuto anche disegni, prototipi e alcune volte si è trasformato in oggetti.

[…] Dico tutto questo ben sapendo che poi gli oggetti a loro volta hanno una effettiva influenza su quello che le persone ‘là fuori’ fanno.

E questa è l’altra componente importante : la presa ‘sul serio’ degli oggetti, ‘delle cose’, il loro essere salvate dalla banalizzazione del funzionalismo, del riduzionismo economico.

[…] il pubblico Alessi ha accettato in maniera sorprendente i cambiamenti di tono, i salti drastici, le virate a U di questi ultimi anni; questi sono accettabili come lo sviluppo di un discorso perché il parco di oggetti creato rimanda a un collezionista originario.

Come per il personaggio di un romanzo di Bruce Chatwin, Utz, le ragioni del collezionista di porcellane formano una storia intrigante, che lascia sempre adito a interpretazioni e che nasconde una leggera o forte ironia. Utz, nel romanzo di Chatwin è un collezionista? Una spia? Un uomo felice o disperato? O è uno che in qualche modo ha sempre mantenuto l’ironia e la cui collezione è una manifestazione dell’ambiguità e della ricchezza del mondo?

[…] Ed è divertente notare che la metafora della finestra adoperata prima per dire che il centro studi ‘riflette’ sul destino (e riflette il destino) degli oggetti là fuori, sul modo con cui noi oggi ci facciamo fare compagnia dagli oggetti, rimanda a sua volta alle vetrine vere, quelle in qui gli oggetti Alessi sono in mostra. Gli oggetti Alessi formano anche in vetrina un contesto[…] In questo senso gli oggetti ‘si animano’ e formano storie (e si mettono sulle loro zampe) […]

Ma c’è qualcosa che è cambiato negli ultimi anni: al funzionalismo e poi al funzionalismo della bellezza da collezione si è aggiunto il rimando degli oggetti al loro uso affettivo e da questo all’uso di essi come tramite di relazione. Sono collezioni, sì, ma collezioni che rimandano a relazioni che la gente può stabilire tramite oggetti. Attento a quello che il mondo comincia a sentire là fuori, il centro studi comincia ad occuparsi del fatto che […] gli oggetti sono tramite di relazioni, di alleanze, di litigi, di malintesi, di odii e di amori. Si apre un’altra stagione di ricerca e la contestualità di cui le collezioni si facevano metafora diventa adesso una contestualità di relazioni interpersonali.

Gli oggetti passano di mano in mano, si appoggiano tra corpi, toccano e si fanno toccare da uomini e donne, ne deviano o facilitano i contatti, diventano il presente o il ricordo, il regalo o la restituzione, il ‘ti do questo per farti capire come sono’ […]

Franco La Cecla, 1996

Story

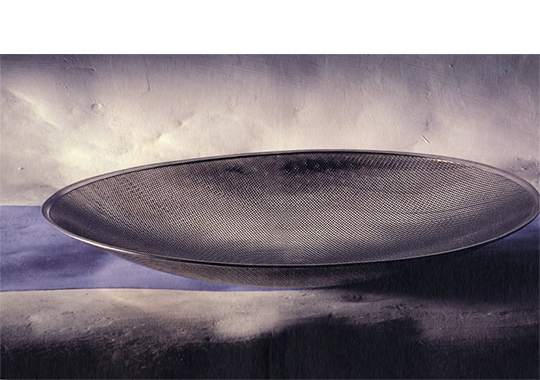

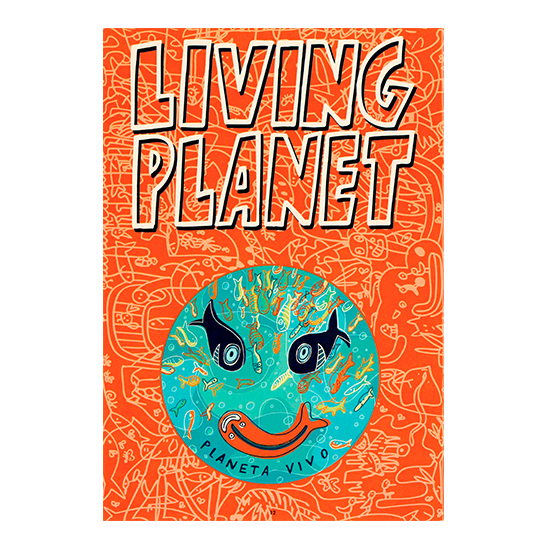

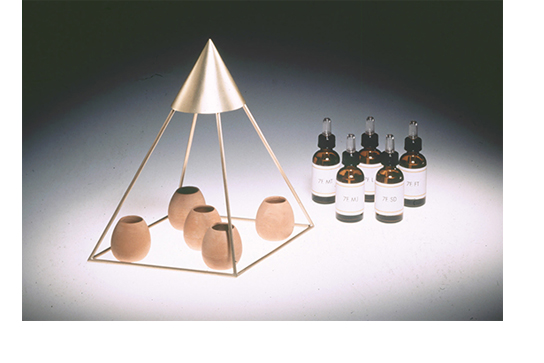

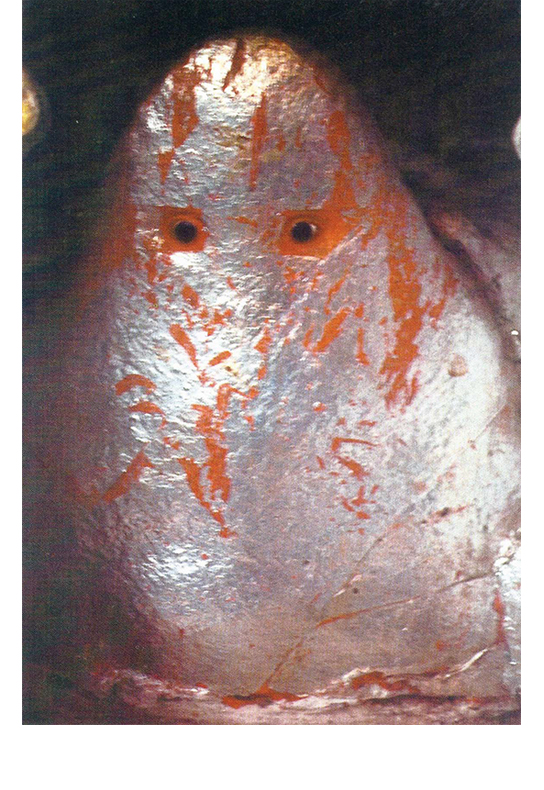

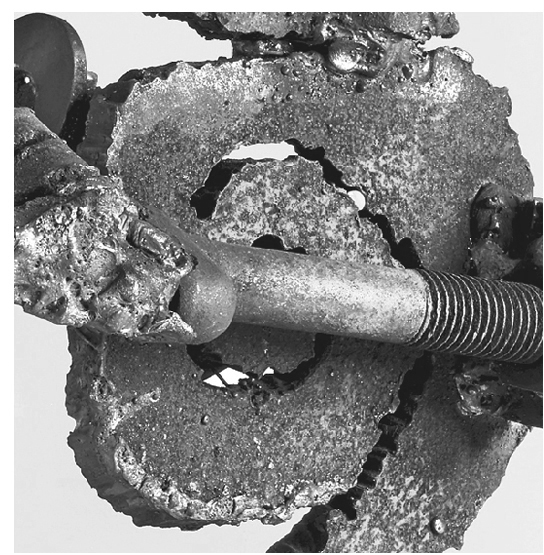

The Balanced Object 1996

“The Object of Balance” was a product and a publication, but especially it marked a moment of reflection on the work conducted by the Alessi Study Centre up till that time. It was 1996 and we had concluded the first six years of activity: the small, but significant, revolution accomplished in the design world had reached its maturity. With our work, we had reacted against what had then seemed to us like a veritable invasion of objects created by a misunderstanding of design, by its vulgarization, “design for design’s sake.” Self-referential, “conceited” objects that were distant, incapable of establishing an effective relationship with people. So we tried to create completely different objects, born from an “ensemble” design that would integrate different knowledge and criteria borrowed from domains outside the traditional reaches of design. Interdisciplinary and comprehensive application. These two words expressed the new approach we wanted to practice, the only one that could lead to objects capable of relating with people, to products that could be approached, desired and used in a reciprocal relationship.

“The Object of Balance” marked a key moment in this process which tried to assert a new relationship between design and research, comprising a range of contributions and various forms of knowledge.

“The object of balance is entirely generated by relationships of the golden ratio and can be considered the synthesis of finite and infinite: finite material form that creates a movement of vital infinite energy by cooperating to overcome stagnation. Its function is to reactivate an environment burdened with immobility, restoring vital motor energy and consequently balance and well-being ” Enza Ciccolo

Conceived as part of the “Biological Project”, this object consists of a triangular prism that breaks up light. Inside, there are five small terracotta pots that contain “white light waters.” Long studied by Enza Ciccolo, the “white light waters” have “vibrational frequencies” that act on people and, in general, on all living organisms. Thanks to these properties, these waters can be used for therapeutic purposes, for energy rebalancing and harmonization of the environment.

“The Object of Balance” was a clear statement of the nature of the products that we wanted to accomplish. Objects for whose creation it would be necessary to go beyond the correct application of functional, aesthetic, production and trade criteria but, these values would be united with high “harmonic” and relational quality. “Therapeutic” objects able to create well-being and harmony.

“L’Oggetto dell’Equilibrio” fu un prodotto e una pubblicazione, ma soprattutto segnò un momento di riflessione sul lavoro svolto dal Centro Studi Alessi fino a quel momento. Era il 1996 e avevamo concluso i primi sei anni di attività: la piccola, ma sostanziale, rivoluzione compiuta nel mondo del progetto era giunta a una sua maturità. Con il nostro lavoro avevamo reagito a quella che ci era sembrata una vera e propria invasione di oggetti nati da un fraintendimento del concetto di design, dalla sua esasperazione e volgarizzazione, dal “design per il design”. Oggetti autoreferenziali, “presuntuosi”, che allontanavano incapaci di un’effettiva relazione con le persone. Così, avevamo cercato di creare oggetti completamente diversi, nati da una progettazione “corale”, non autoreferenziale, capace di integrare saperi diversi e criteri presi a prestito da ambiti esterni a quello del design. Interdisciplinarietà e trasversalità, in questi due termini si esprimeva il nuovo approccio che cercavamo di praticare, il solo in grado di portare a oggetti capaci di entrare in relazione con le persone, a prodotti che potessero essere avvicinati, desiderati e usati in un rapporto di reciprocità.

“L’Oggetto dell’Equilibrio” segnò un momento fondamentale di questo processo in cui si cercava di affermare quel nuovo rapporto tra progettazione e ricerca, fatto di contributi e saperi differenti.

“L’oggetto dell’equilibrio è interamente generato da relazioni di proporzioni auree e può considerarsi sintesi di finito e infinito: una forma materiale finita che crea un movimento di energia vitale infinito cooperando al superamento della stasi. La sua funzione è infatti di riattivare un ambiente gravato da staticità, ripristinando il moto dell’energia vitale, quindi l’equilibrio e il benessere” Enza Ciccolo

Nato come parte del “Progetto Biologico”, questo oggetto è costituito da un prisma triangolare che scompone la luce, al cui interno si collocano cinque piccoli contenitori di terracotta che accolgono delle “acque a luce bianca”. A lungo studiate da Enza Ciccolo, le “acque a luce bianca” sono dotate di “frequenze vibrazionali” che agiscono sugli uomini e, in generale, su qualsiasi organismo vivente. Grazie a tali proprietà queste acque possono essere usate a scopo terapeutico, per il riequilibrio energetico e l’armonizzazione dell’ambiente.

“L’Oggetto dell’Equilibrio” fu un’esplicita dichiarazione della natura dei prodotti che desideravamo realizzare. Oggetti per la cui produzione non bastava più la corretta applicazione di criteri funzionali, estetici, produttivi e commerciali ma, a questi valori, univano un’elevata qualità “armonica” e relazionale. Oggetti “terapeutici”, in grado di creare benessere e armonia.

Story

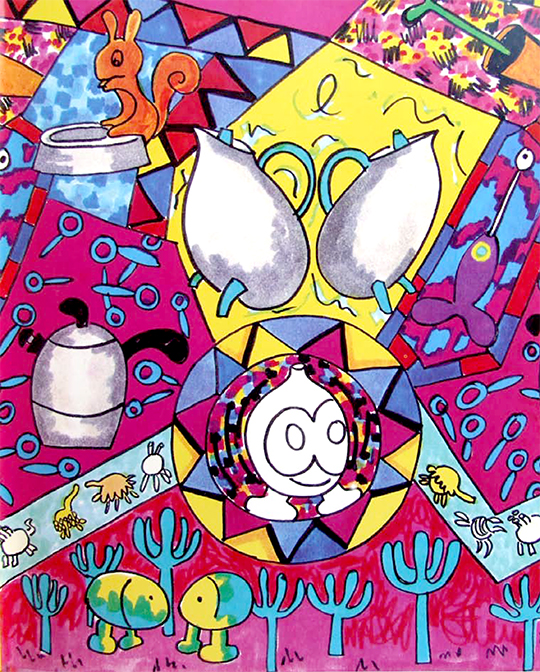

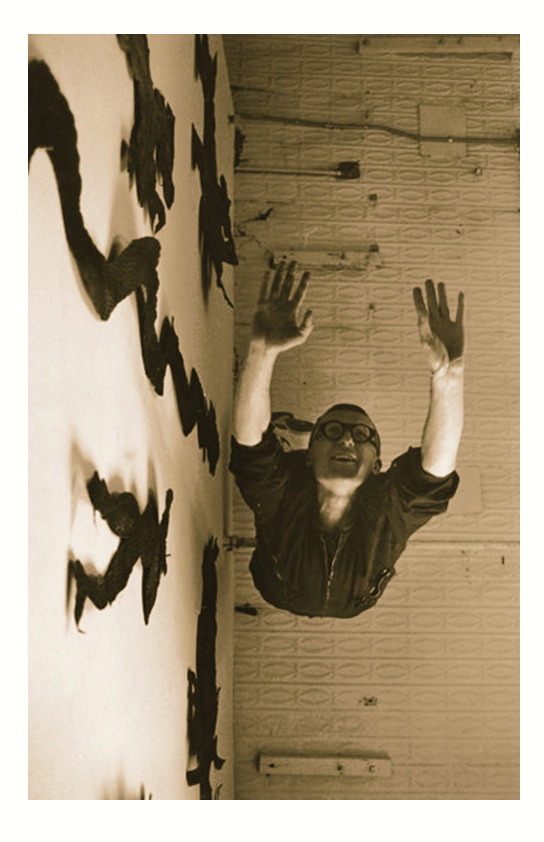

Marcello Jori

14/02/2016

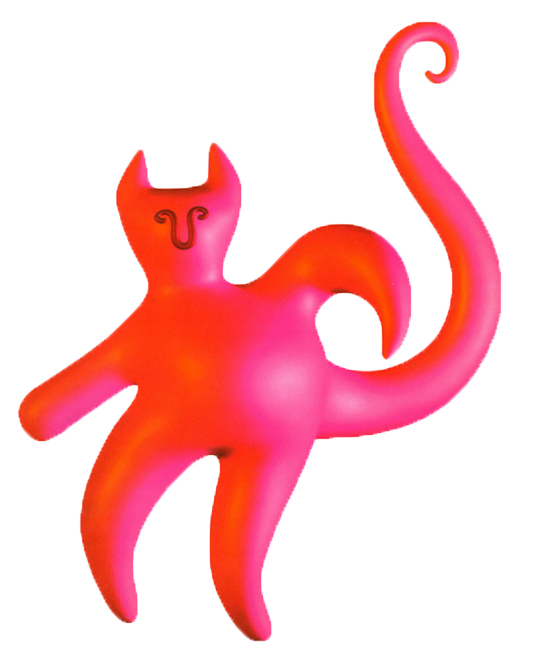

“Ho incontrato Laura Polinoro alcuni anni fa, nel suo laboratorio di Milano. All’epoca era direttrice del Centro Studi Alessi e da subito mi lanciò la prima sfida dal fronte del design. Intorno a lei c’era grande profumo di novità e di ricerca, tale da indurmi a decidere che, se mai avessi fatto opere da designer, sarebbe stato solo con Alessi e con Laura.

E così è stato: con Alessi realizzo quello che non faccio con la pittura e nemmeno con la scrittura. Con Alessi mi impegno a fare arte utile, anche se il mio campo d’azione non è l’ambiente calpestabile di una cucina o di un ufficio.

I miei oggetti non servono solo a cucinare cibi o a sollevare pentole, ma vogliono sollevare lo spirito, accendere il sorriso. Sono oggetti quasi vivi, che sviluppano affetto e raccontano storie; il loro scopo è abbellire l’invisibile. Con Alessi cerco di creare figure che si appoggino nelle teste e cambino la forma dell’umore.

Laura è per me la complice perfetta per la sua capacità di vedere le forme dei pensieri giusti ancora prima che diventino concreti. Insieme discutiamo ed elaboriamo tali pensieri finché non risultano convincenti: Laura ed io cerchiamo insomma di emozionarci.

È solo in un secondo momento che quei pensieri giusti si incontrano con Alessi per diventare finalmente pensieri utili.”

“I met Laura Polinoro a few years ago, in her workshop in Milan. At the time she was director of the Centro Studi Alessi and she immediately gave me the first design challenge I had ever faced. An aire of innovation and experimentation surrounded her, enchanting to the point of persuading me: if ever I were to work as a designer, it could only be with Alessi and only with Laura.

And so it was. With Alessi I do what I don’t do with my painting or even in my writing. With Alessi I am committed to doing useful art, even though the scope of my projects does not extend to the nuts and bolts of a kitchen or an office.

My objects are not simply for cooking foods or lifting pots. They aspire to lifting spirits, lighting up smiles. My objects are almost alive, nurturing affection and telling stories; their purpose is to beautify the invisible. With Alessi I try to create figures that alight gently in the mind and modify the shape of a mood.

For me, Laura is the perfect accomplice thanks to her ability to see the shapes of the right thoughts even before they become practical. Together we discuss and process these thoughts until they become convincing: in short, Laura and I try to amaze each other.

It is only later that those ‘right thoughts’ simply come together in Alessi, becoming, in the end, useful thoughts.”

“Ho incontrato Laura Polinoro alcuni anni fa, nel suo laboratorio di Milano. All’epoca era direttrice del Centro Studi Alessi e da subito mi lanciò la prima sfida dal fronte del design. Intorno a lei c’era grande profumo di novità e di ricerca, tale da indurmi a decidere che, se mai avessi fatto opere da designer, sarebbe stato solo con Alessi e con Laura.

E così è stato: con Alessi realizzo quello che non faccio con la pittura e nemmeno con la scrittura. Con Alessi mi impegno a fare arte utile, anche se il mio campo d’azione non è l’ambiente calpestabile di una cucina o di un ufficio.

I miei oggetti non servono solo a cucinare cibi o a sollevare pentole, ma vogliono sollevare lo spirito, accendere il sorriso. Sono oggetti quasi vivi, che sviluppano affetto e raccontano storie; il loro scopo è abbellire l’invisibile. Con Alessi cerco di creare figure che si appoggino nelle teste e cambino la forma dell’umore.

Laura è per me la complice perfetta per la sua capacità di vedere le forme dei pensieri giusti ancora prima che diventino concreti. Insieme discutiamo ed elaboriamo tali pensieri finché non risultano convincenti: Laura ed io cerchiamo insomma di emozionarci.

È solo in un secondo momento che quei pensieri giusti si incontrano con Alessi per diventare finalmente pensieri utili.”

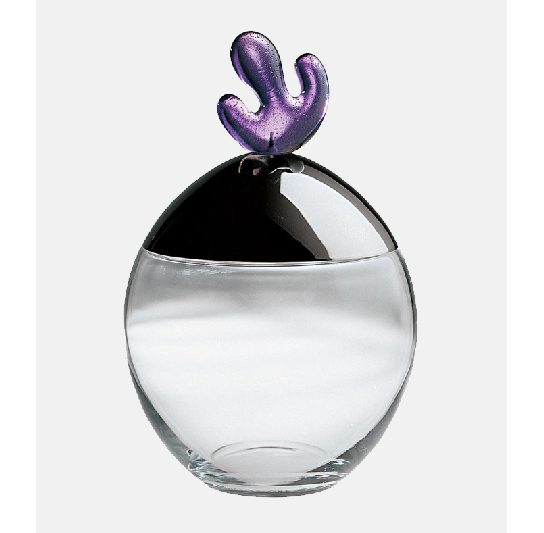

Story

Painted Box (1993)

Why restrict the act of designing exclusively to design professionals? I have always believed in contamination, in tapping a broad spectrum of creative fields, with an open mind, outside the constraints of specialists. From the beginning, I imagined that the research done by the Centro Studi Alessi could include practitioners from a variety of creative disciplines: artists, designers, painters, illustrators, cartoonists… And they, in turn, could work creatively alongside researchers and professionals with a wide range of backgrounds: from linguistics to psychoanalysis, from anthropology to semiotics. The experience of the Centro Studi was formidable precisely due to this ever-evolving reflection, a continuous process of elaborating multiple contributions in a forum of dialogue and mutual influence.

Nuala Goodman was among the first young artists with whom I started working. The collaboration with her bridged two experiences that were developing in those years: the first being work of the newborn Centro Studi; the second a new brand, “Alessi Twergi”, founded by the company in 1989 to produce a new collection of wooden objects. The use of wood opened up new linguistic possibilities: objects that were intimate, special, relating to codes other than those related to steel, the primary material for the majority of Alessi’s products up till that point.

Nuala Goodman’s poetic and dreamlike language seemed perfectly suited for exploration in wood. After the first workshop on “Memory Containers”, wood became the material of choice for the new additions to the collection.

Wood was used in the creation of many objects: small works of architecture; containers whose features resembled miniature constructions; small houses, which are also custodians of memory. Hand-decorated by Nuala, the boxes took on a life of their own through her soft and oneiric approach to painting.

“Tree of Life”, “Heart”, “Faces in blue”. These are some of the evocative titles chosen for a limited edition of memory containers presented in 1994.

The collection was produced in India, by craftsmen who faithfully reproduced the paintings made by Nuala on the first series of “Painted Boxes”.

Perché racchiudere l’esperienza progettuale esclusivamente nella collaborazione con i professionisti del design? Ho sempre creduto nella contaminazione, nel lavorare con il mondo della creatività in tutte le sue espressioni, senza preclusioni specialistiche. Fin dall’inizio ho immaginato che la ricerca del Centro Studi Alessi potesse coinvolgere autori provenienti da discipline creative diverse: artisti, designer, pittori, illustratori, cartoonist… E che questi, a loro volta, potessero lavorare creativamente con ricercatori e professionisti provenienti da campi differenti, dalla linguistica alla psicanalisi, dall’antropologia alla semiotica. L’esperienza del Centro Studi è stata formidabile proprio per questa riflessione sempre in divenire, un continuo elaborare contributi diversi in dialogo e reciproca influenza.

Nuala Goodman fu uno dei primi giovani artisti con i quali iniziai a lavorare. La collaborazione con lei costituì una cerniera tra due esperienze che si stavano sviluppando in quegli anni. Il lavoro del neonato Centro Studi e l’esperienza di “Alessi Twergi”, marchio con il quale l’azienda aveva inaugurato nel 1989 una nuova collezione di oggetti in legno. L’uso del legno aveva aperto nuove possibilità linguistiche: oggetti intimi, particolari, afferenti a codici diversi da quelli legati all’acciaio, il materiale con il quale Alessi aveva fino ad allora realizzato la maggior parte dei suoi prodotti.

Il linguaggio onirico e poetico di Nuala Goodman appariva perfetto per una ricerca sul legno. Dopo il primo workshop dedicato ai “Memory Containers”, il legno si offriva come materiale d’elezione per nuovi “contenitori della memoria”. Con il legno vennero create delle piccole architetture, dei contenitori le cui fattezze ricordavano delle costruzioni in miniatura. Piccole dimore, custodi anch’esse di una memoria. Le scatole si animarono, affidate a Nuala che le decorò a mano con la sua pittura morbida e immaginaria. “Tree of life”, “Heart”, “Faces in blue”, questi alcuni dei titoli evocativi scelti per i contenitori di memoria presentati nel 1994 in edizione limitata.

La collezione fu prodotta in India, da artigiani che riprodussero fedelmente le pitture realizzate da Nuala sulla prima serie di “Painted Boxes”.

Story

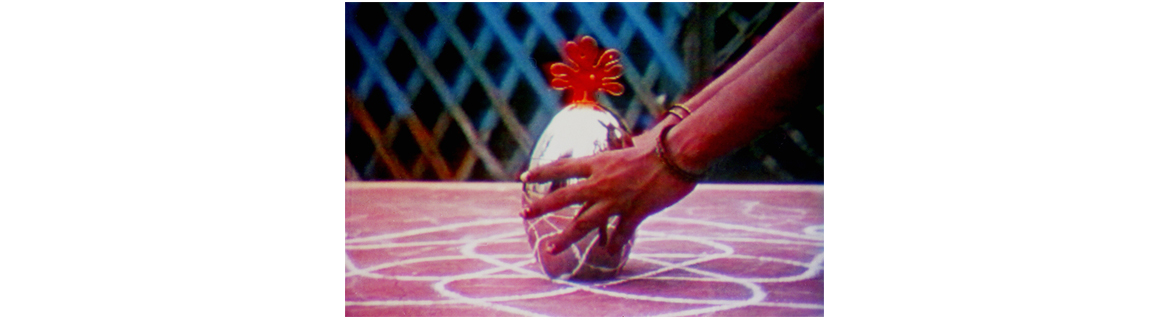

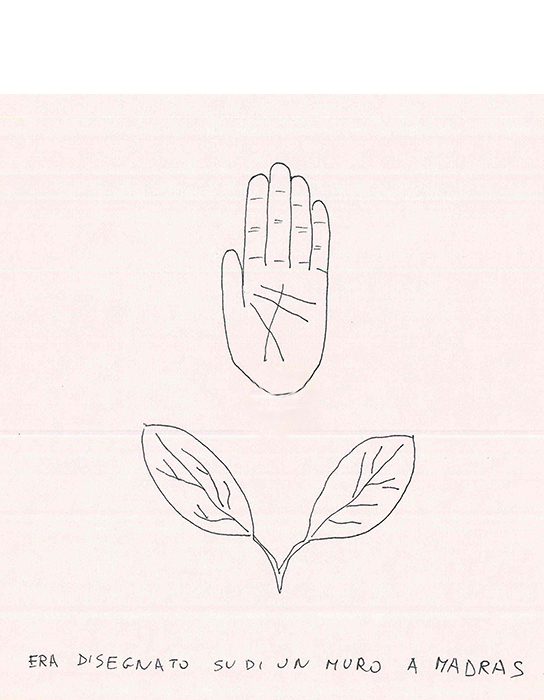

Shama’s Welcome

“To the cosmic intelligence

to the guardian angels

to the enlightened masters

to men of heart

to women of action

to all the creatures of the Universe

It goes without saying objects assume their own forms, by themselves, drawing from the infinitely profound territory of the collective unconscious. Ours is an age in which the tribes acknowledge each other, in order to reunite in ancient families. The task of objects is to symbolically evoke lost messages. The true secret remains forever incommunicable; it cannot be borne on a whisper, from mouth to ear. To possess it, on must reach the point of assimilating it spiritually, discovering it within oneself. The discovery is made by way of symbols, which speak eloquently to the independent thinker. Our condition as designers is that of being in the world, totally. We belong to a tribe that concerns itself with the transformation of energies. For us, ‘the great work’ can also be accomplished trough objects.

While travelling for the first time in India, I decided to try working in a new way as a designer, with an empty mind, free of preconceived ideas, allowing external forces to guide me to the heart of creativity and to provide the responses to the questions posed by making objects: why abd for whom? I imagined objects that could put human beings in contact with the divine, capable of recounting ancient stories. My own values as a designer were confirmed by this: if one cultivates a condition of receptiveness, it easy to tune into the secrets of the world as they emerge from fire, from the wind, the stars. The forms and responses we seek are there, waiting for us.

The journey to India left a profound mark within me; I chose to immerse myself in its ancient memory. I worked with archetypal forms, with cosmic symbolisms, seeking to create contemplative, possible even magical objects. It is not with domesticity that I wish to concern myself, but ‘cosmicity’, if you will. It’s like a progressive shifting of one’s point of view. I find it impossible to think about any one thing without seeing the interdependence of all the phenomena of the universe. I believe that the possibility of making a genuine qualitative leap forward along the path of human evolution depends on our capacity to see beyond. If the designer is truly a creator, her work is thus an existential mission dedicated to the care of her own soul and those of people around her. Our responsibility as women is to be always aware of the fact that work in itself is not an affirmation of the ego. The feminine way is not the accumulation of power but the continuous giving of energy, knowing all along that there exists a cosmic intelligence capable of revealing everything to us. For me, success means finding the harmony between being and making.

I work with the belief that, through the use of quotidian objects, one can reach the path of awareness: all objects have soul, and they dance together with human beings in a cosmic dance, in harmony with the whole of existence.